Ed Christie’s career lending life to fabric started when he was five years old. And he had a following: kids from his Elmont, N.Y. neighborhood would flock to the puppet shows he put on.

Back then, Christie’s characters were inspired by hand puppets he saw in television programs like The Chuck McCann Show, he says, which featured Paul Ashley’s versions of Hollywood personalities.

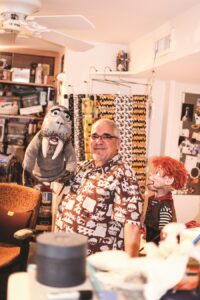

“With puppets, you have to do half the work for them,” Christie says, peering down affectionately at a Cary Grant rod puppet he acquired at an auction of Ashley puppets last year.

He learned early on that a lot of work goes into wielding a puppet compellingly. “Puppets are just sculptures,” Christie says. “You have to make them lively and expressive on their own, and then of course they’re still just dead on a stick. The puppeteer has to bring them alive and make them convincing to people.”

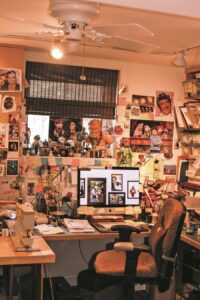

At Christie’s house in Truro, where he lives with his husband, Independent arts writer Howard Karren, whole rooms are archives of art — folded, propped, and hung — of which he is either the maker or a fan.

Christie’s puppet passion faded away in adolescence when musical theater governed his creative energies. But in the spring of 1978, a degree in art education from UMass Amherst just one semester away, Christie secured an internship at Henson Associates, now the Jim Henson Company, the enterprise behind the Muppets.

“It was a heady time for Henson,” Christie recalls. The Muppet Show was two years old; Sesame Street had been on TV for 10; and Henson had a slew of projects in line to catapult the company to even greater acclaim.

Christie was on duty during the filming of The Muppet Movie that summer in Los Angeles. When he was hired back after finishing his degree in the fall, he found himself graduated from the “gofer” status of his internship days and tasked with what’s known as “puppet wrangling.”

“I was the person who tended to the puppets,” Christie says. He would fetch them on cue and make sure they were aptly suited up — dressed, with props sufficiently secured — for the scene to come.

“If Bert was holding something, it had to be taped and pinned into his hand,” Christie says. Protocol was different for Ernie, who’s a live-hand puppet. Because the puppeteer brandishes Ernie’s body with one hand and controls the puppet’s hand with the other, Ernie can actually grasp objects.

Behind the animated joviality of Muppet skits, there was always plenty of technical handiwork to do — some of it unglamorous. “With performers sweating, the puppets kind of rot from the inside,” Christie says. “The classic Muppet Show characters wore out very quickly.” Big Bird had to be remade every two years.

“It’s not a dirty business,” Christie laughs, “but there are consequences.”

On the side, Christie tried his hand at pattern making and puppet building, practices that showed him how inextricable puppets can be from their designers’ personalities. Sometimes the puppets even look like their makers in strange, abstract ways, he says.

Recalling the throngs of Muppets positioned on sticks in Henson’s studio, Christie says, “I could tell you which of the puppet builders built which puppet.”

Following years of making minor characters that could be sketched up and whipped into reality with just a few days’ sleight of hand, Christie was the designer behind three more prominent Muppets: Rosita, Zoe, and Abby Cadabby. He’s proud of the fact that those three characters were the main female characters on Sesame Street, and that they’re still in the cast.

All are sweetly beastly and vaguely anthropomorphic. “I wasn’t good with humans,” says Christie. “I did animals pretty well — and I did monsters really well.” Christie won eight Emmy awards for his Sesame Street designs, which traveled the world.

Leading up to each country’s production, designers and producers would consider the location’s cultural parameters. Things usually went well, though in 1997 the company attempted an Israeli-Palestinian co-production that would defy geopolitical odds. In that case, “Things fell apart,” Christie recalls. “The Israelis took their puppets and did a show, and the Palestinians took their puppets and did a show.”

Zeliboba, the “Big Bird” of Sesame Russia, is a walkaround creature made from wispy tendrils of blue organza, loosely mounted. “It’s my favorite thing I’ve ever designed,” Christie says. But a puppeteer can’t get too attached. Once a puppet has been created, “you let it go. Someone else is going to take it somewhere else.”

Christie moved to Truro in 2004 and continued designing for Sesame Workshop from afar until 2015, when he spun his fabric-meets-character work into two of his own artistic endeavors: table runners and sculpture.

For the table runners, Christie pieces together vibrant patterned hues and sells the finished decorations exclusively at Jobi Pottery in Truro.

Cleaning out the dryer filter while preshrinking fabric for his early table runners, Christie found himself staring at something too beautiful to bin: “I collect lint,” he says.

“People save me their dryer lint, and they send it to me in the mail,” he adds. Christie’s most distant lint supplier is in the U.K. The lint is separated by color in the gorgeous mayhem of his basement studio, where puppets watch over table runners stacked neatly next to a talking bell named Isabel (she was a merchandise item related to a Sesame Street co-production).

Christie mixes the lint with resin, then sculpts. He shows the marbled outcomes, whose surfaces look unsettlingly natural, at Karren’s Alden Gallery in Provincetown.

One of his sculptural series recalls the kind of character creation Christie practiced in puppet making. For it, Christie pours resin into a cartoonishly big-featured, bald-headed mold he’s named Ricky.

Variations include a silky-white Milk Ricky sprouting clusters of correspondingly snowy facial hair. His pale-yellow counterpart, Cheesy Ricky, has pleasing little Emmental-looking dimples all over his face. Rainbow Ricky has a rainbow cascading from his mouth.

Though puppets seem a thing of the past for Christie, Ricky seems to reawaken a puppetmaker’s relationship to his creations: “I kind of identify with him,” Christie says.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article, published in print on April 13, erroneously identified the program for which Christie created the character Zeliboba. It was Sesame Russia, not Muppets Russia.