I didn’t think I needed the potato clock. I mean, everything I really need is close by: I can buy my printer paper across the street from here. If I get a bagel jones I can go next door. They’ve got the chive spread, too. No, the potato was not on my radar.

The Earth House in Orleans is a Three Kings kind of place. The fragrance of frankincense and myrrh mingle with the salty breeze making the wind chimes and dream catchers drift, swing, and sing. There is some vinyl cued up. It might be Fleetwood Mac. It isn’t Blonde on Blonde. I’m sure of that.

Posters speak of history. John Carlos’s and Tommie Smith’s gloved fists are raised in black and white. Dr. King. Mahatma Gandhi. Marley. Mandela stands next to Malcolm. Across the bottom, these words: “A man who stands for nothing will fall for anything.” —Malcolm X.

A guy named Dylan owns this shop. I’m not making this up. He and Robin. “Once upon on a time (June 23, 1990)” reads the story on the Earth House website, “on a sandbar sitting in the Atlantic Ocean the happy newly married couple of Robin Sullivan and Dylan Stanton set about to open a shop to change the world, one T-shirt and bumper sticker at a time.”

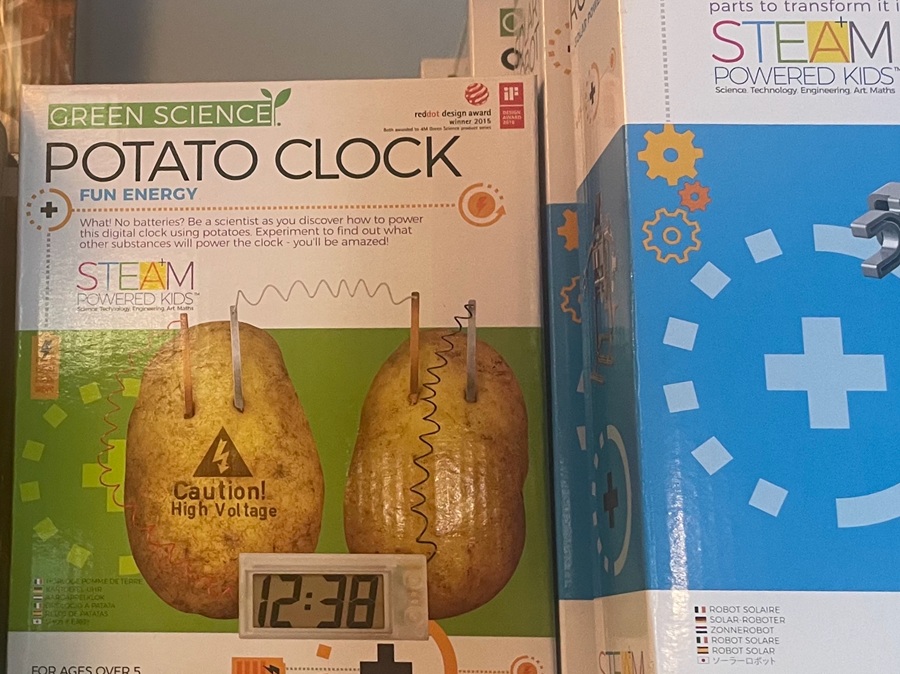

Books, crystals, incense, and jewelry comingle here. There are some sticks that promise to make my house smell like a temple. Patchouli would be plain-Jane. There’s that clock, digital, and DIY; it will run on the electrochemical power hidden within a couple of potatoes. Also, pages pertaining to the ecstatic and metaphysical pack the shelves and offer advice that might be useful in these troubled times: Psychic Self-Defense stands not far from The Evil Eye, their straight spines separated only by Live Like a Goddess. Above them a sign: “Modern Americans behave as if intelligence were some sort of hideous deformity.’’ —Frank Zappa.

A woman sits at the checkout counter, half-buried behind Equal Exchange chocolates. She’s pricing smudge sticks. I wonder out loud about the clientele. Megan doesn’t tell me her last name, but she fills me in: “Our feistiest crowd is the 70-year-olds,” she says. “It’s their safe place. With all that’s going on these days, they don’t worry about their words.”

Dylan appears, attired in a tie-dyed T-shirt. His white hair stands wildly windblown, and I’ll bet you a vintage Beatles album that it’s not salon product he’s using. He regales me, at triple espresso speed, with stories of when he first landed in Provincetown after a stint at art school. As he freewheels, Robin smiles and keeps sticking price tags on album covers.

“I was really wanting to meet Jackson Lambert,” says Dylan. “He was a town fixture then, drawing for the Advocate. I was at the Bradford, and I asked someone about him. ‘You want to meet him?’ they asked me, ‘Because he right here.’ ”

Instant Karma Records might be considered a subsidiary of the crystalized, gem-stoned, poster-plastered Earth House. Recently, a young friend of mine bought a house in which the previous owners left two old stereos and some vinyl. He needed a tutorial on how to cue up the Brubeck. I’ve long ago discarded my carved-up hiss and pop collection. I’ve lost the high range. But vinyl is back, and the stacks here are impressive.

The record covers, their designs, work like madeleines, triggering powerful memories: Clapton, Cream, James Brown, Chicago, Joe Cocker, the Stones, Donna Summer. I’m at the back room. DJ Pat at the turntable chimes in, apropos of nothing, “Did you hear about the guy trying to bring back pay phones?”

“Yeah, that’s far out,” I say before I can catch myself. Then I spy R. Crumb’s portrait of Janis Joplin. “You don’t happen to have Crumb’s book Genesis, do you?”

“No,” she says, “but I’m sure Dylan does.” He’s a huge R. Crumb fan. On the wall are some of Stanton’s art works, including a pen-and-ink Eric Dolphy’s in Heaven and his T-shirt design, “Just One More Record.” Definite R. Crumb influences, but certainly he has his own distinct vision. On the wall is this: “One good thing about music — when it hits you, you feel no pain.” —Bob Marley.

The Earth House calls itself “a gift shop for planet Earth,” but it is also, inescapably, a museum and a piece of theater. In the final act you can drop down into the lower level along a carpeted stairway that’s edged with floor lights. Down here there’s a wonderful jumble.

What to make of it? There’s an old manual typewriter and behind it leaning lazily is a copy of Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters. A Steely Dan cover stands sideways next to a turntable, its needle stopped between grooves. I pick up a well-read copy of a James Brown biography.

I’m in the Filene’s Basement of the counterculture, and I’m glad someone hasn’t tossed it all in the dumpster. I have to pick up that potato clock before I leave. One last quote follows me out: “A winner is a dreamer who never gives up.” —Nelson Mandela.