At first glance, the vessels in a vitrine at the Cahoon Museum of American Art look like relics of the 19th-century whaling industry: their mottled surfaces resemble bone, and they’re etched with portraits of stern-faced captains. But step closer and you’ll see that these are plastic jugs salvaged from a beach and reimagined by artist Duke Riley to tell a different maritime story.

The tension between reverence for vernacular traditions and a reckoning with our contemporary ecological crisis animates “What the Waves May Bring,” Riley’s exhibition at the Cahoon Museum in Cotuit, on view through Sept. 14. The artist, who spends much of the year living on a boat docked in Bristol, R.I., worked as a tattoo artist while studying at the Rhode Island School of Design. He draws inspiration from the visual language of sailor tattoos, scrimshaw, and sailors’ valentines, and he brings those folk forms into the realm of contemporary art, transforming them into wry, mournful commentaries on plastic waste in the ocean.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is the Poly S. Tyrene Memorial Maritime Museum, a series of vitrines containing plastic detritus scavenged from beaches in New York and New England. Riley coats bottles and jugs in acrylic paint and wax to give them a soft ivory sheen with fine striations resembling whalebone. Onto these ersatz bones, he inscribes drawings in the manner of 19th-century scrimshaw.

The faces in his portraits are not those of whaling magnates but of today’s petrochemical executives: Dennis Jönsson of Tetra Pak, Emmanuel Faber of Danone, and J. Peter Grace of W.R. Grace & Co. In one piece, a woman in a hoop skirt stands by the shore, looking out to the sea like a whaler’s wife and clasping a flimsy “Thank You” shopping bag. Another work depicts a swordfish spearing a six-pack ring — a grim update to nautical lore.

Nineteenth-century scrimshaw often celebrated the men who drove whales toward extinction. Riley’s scrimshaw confronts the industries that have replaced whale products with petroleum-based plastics — an even more destructive inheritance.

On another wall, Riley’s installation Bait (2025) reimagines everyday refuse as fishing lures. Mounted in glass cases, his brightly painted assemblages are fashioned from hypodermic needles, toothbrushes, toy figurines, bullet casings, even dildos. Some resemble the glinting artificial lures sold in tackle shops; others seem more grotesque, like fish already gutted. Fishing lures are designed to fool marine life into mistaking plastic for food. Bait is a reminder that plastic debris already performs that deadly trick.

The Cahoon Museum is a fitting site for Riley’s work. The museum honors Ralph and Martha Cahoon, along with their collaborator Bernard Woodman, who kept Cape Cod folk traditions alive in the 20th century by reinventing them for new audiences. Ralph Cahoon’s whimsical paintings of mermaids and sailors epitomize local mythology. Riley, who cites Ralph Cahoon as an influence, spent summers on the Cape as a child and visited the museum with his grandmother on rainy days.

Cape Cod also shaped his sensibility more broadly. Riley says that on his visits to Provincetown as a teenager he absorbed what he calls the “psychogeographic relationship” between coastal communities and the sea. But the connection to place in his work is not about any particular site. “It’s about the semi-nomadic transient cultures that form around the waterfront,” he says, “and how they connect people from different backgrounds.”

That insight informs Riley’s fascination with scrimshaw and tattoos, which employ the same tools, inks, and motifs. In the cramped quarters of 19th-century whaling ships, crews drawn from every corner of the globe developed hybrid visual languages, inscribing them on skin and bone alike. Riley sees this cross-cultural vernacular as a democratic counterpoint to the destructive hierarchies of maritime industry.

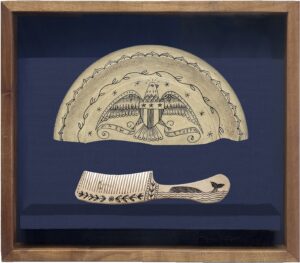

Perhaps the most poignant works in the show are Riley’s sailors’ valentines. These mosaics, fashioned from colorful shells and housed in octagonal wooden cases, were popular souvenirs in the 19th century. Sold in Caribbean ports like Barbados, they often included tender messages spelled out amid concentric rings of shells.

Tomorrow Is a Mystery (2021) uses some shells, though it is dominated by plastic found on the shore. A mosaic of black bottle caps fills one side of the box with a void-like darkness, replacing the cheerful hues of traditional shellwork. “I started noticing there were fewer shells and more and more plastic on the beaches,” Riley says. “So, I began making valentines that accurately reflected the environment.”

The gesture is both conceptual and ecological: Riley removes plastic from circulation by enshrining it in art objects. He partners with Laura Ludwig, director of the marine debris and plastics program at the Center for Coastal Studies in Provincetown, to source the thousands of pounds of plastic that his studio requires. Upcycling trash into art may not be as scalable as other solutions to eliminate waste, but Riley’s elegiac souvenirs provide visibility and emotional impact.

In the end, “What the Waves May Bring” is less about nostalgia than about continuity. Riley honors the visual traditions of Cape Cod and the wider maritime world, but he does so by dragging them through the waste of the present. His scrimshaw is scratched into milk jugs, his valentines bloom with bottle caps, his lures are baited with the excesses of modern consumerism. By placing these objects in a museum, Riley elevates them without sanitizing them. They remain stubbornly what they are: evidence of a civilization that treats the ocean as both a cultural reference and a dumping ground.

What the Waves May Bring

The event: An exhibition of artwork by Duke Reily

The time: Through Sept. 14

The place: Cahoon Museum of American Art, 4676 Falmouth Road, Cotuit

The cost: Free