WELLFLEET — Duck Harbor, enjoyed by visitors as a bayside beach, is returning to its 19th-century roots as a salt marsh, according to Tim Smith, a restoration ecologist at the Cape Cod National Seashore who is studying the ecological transition here. And Smith doesn’t mean “roots” as a metaphor: the seeds of saltwater plants that have lay dormant for more than 100 years are sprouting there, including glasswort, seablite, and seaside orach, he said.

After seawater repeatedly breached a coastal dune and poured into the freshwater confines of Duck Harbor in 2021, trees behind the bank turned gray and died. With those so-called overwash events continuing since then, bursts of green saltmarsh plants have started to emerge — near the beach at first, but then farther and farther upstream.

These overwashes are not purely a function of rising seas but involve other coastal processes including sand movement, according to Katie Castagno, a geologist and director of the Land-Sea Interaction Program at the Center for Coastal Studies who is also studying the evolution of Duck Harbor. Winter storms could bring enough sand to fill the saltwater pathway inland, she said, which would put a stop to the intrusions, at least for a while.

In the meantime, research on the ecological transition at Duck Harbor can, according to Smith, provide a preview of “what the whole Herring River system will do once tides are restored.”

The decades-long $70-million Herring River Restoration Project, a collaboration between the town and the National Park Service, involves the replacement of a dike that blocks salt water from the mouth of the Herring River with a bridge and gates that allow for the gradual restoration of tidal flow there. The return of salt water to the estuary means a transition in the kinds of vegetation and wildlife that will thrive in the area.

Duck Harbor and the Herring River are part of the same system, Smith said, so what happens at Duck Harbor can help predict what will occur in the restored estuary. “The data we’re collecting are all related,” he said.

Unlike the larger restoration project, the Duck Harbor overwashes were not deliberate. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service did, however, spend $2 million to have 125 acres of dead trees in Duck Harbor turned into mulch in 2023 to help facilitate the transition to saltwater species.

Soil and Species

Castagno said her team from the Center for Coastal Studies is taking sediment samples in hopes of learning how the area has changed “over potentially thousands of years” — a timeframe that should soon be nailed down by lab tests on their oldest samples.

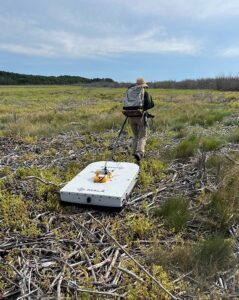

“We were taking sediment cores all last summer,” said Castagno. To get them, her team had to plunge tubes deep into the muck to bring up what lies beneath: layers of peat, clay, silt, and sand that tell researchers about the continuing flux of landscapes and ecosystems here. Her team also used ground-penetrating radar to generate images of underground sediment layers.

The cores don’t only describe the past, Castagno said. “If we’re anticipating erosion in different areas” from sea-level rise, “it will be useful to know what our substrate is that might erode,” she said.

Park Service research in Duck Harbor has included surveys of fish and plant species and measurements of changing soil chemistry. “Last summer we did fish sampling,” said Smith, “trying to quantify the composition and distribution of fish species” in the brackish waters.

The Park Service also established 40 one-meter-square plots in Duck Harbor to record the plant species that are appearing and disappearing in them. Smith is measuring the geochemical response of soils as they are rewetted with salt water.

So far, Duck Harbor is undergoing a “textbook” saltmarsh recovery, Smith said — in the first year after the overwash, salt-tolerant species such as spear saltbush and pickleweed began to flourish.

“When the salt water comes in, it kills these other plants, and it gives these plants a space to survive and to spread,” Smith said. Over the long term, these herbaceous annuals do not typically fill a mature salt marsh, however; on the Outer Cape, that niche belongs to grasses such as the intensely green spartina grass.

Researchers are beginning to see sparse patches of that grass in Duck Harbor, Smith said, indicating that the next stage of the transition to a salt marsh has already begun.

Knowledge about Duck Harbor’s transition has relevance beyond Cape Cod, Smith said. There are many places where humans have restricted tidal flow around or in wetlands, whether with dikes and berms or simply with roads, and people involved in their restoration will be watching this project closely.

The freshwater marshes that often result from the construction of dikes as happened here and other human-made development will be increasingly vulnerable as sea levels and high-tide lines rise, Smith said. Saltwater inundations, and therefore saltmarsh transitions, will likely become more common, whether they happen as part of managed processes or on their own.