At Nauset Regional High School, says Way Yin Yuen, he was known as “that Asian kid.” But, the 1996 graduate says he was largely spared racial smears growing up — save for one incident in middle school. A bully had been sniping insults at him, and, for weeks, Yuen let them ping off — until that classmate got up-close and personal.

The bully’s slur of choice was a rather uninspired “Ching Chong,” spat right into Yuen’s face in the hallway. Yuen kept walking. His tormentor then slugged him from behind. Years of karate training enabled Yuen to land a solid kick, he recalls, “though I botched the landing and fell on my ass.” The ensuing scuffle put both boys in the principal’s office, but playing to stereotypes paid off in this case, Yuen said: from then on, “Nobody wanted to mess with the martial-arts kid.”

Three of Yuen’s grandparents are Chinese, hailing from Guangdong province. His maternal grandfather, Jim Chung, opened the Double Dragon — Orleans’s first Chinese restaurant. Chung’s wife —Yuen’s maternal grandmother — Joyce Robertson, has New England roots.

Throughout his childhood, Yuen’s Grandma Joyce would tell stories about how their ancestors sailed on the Mayflower and penned the first Thanksgiving Day proclamation. Years later, as an adult, Yuen has sifted through dozens of town documents and anchored these childhood tales to historical records. He laid out his family tree in a talk on Oct. 7, at the Centers for Culture and History (CHO) in Orleans.

Mayflower Roots

Yuen, who now lives in Harwich, has earned membership in two local genealogical organizations: the General Society of Mayflower Descendants and the Descendants of Cape Cod and the Islands. The former, Yuen said at the CHO, is among “the hardest genealogical groups to join.” Yuen had to track down birth, death, and marriage records for six generations back from his Grandma Joyce. (The remaining four generations were already documented by the society.) All three kinds of documented proof were required.

After pinning down the names of his relatives, Yuen sought out their stories. That’s when he found a bold, snippy 13th great-grandmother named Susannah Martin, who was hanged at Proctor’s Ledge during the Salem witch trials. And he identified several ancestors who were patriots of the American Revolution. Also in the mix: one loyalist, who spied for the British, and an anti-Quaker sheriff, who, as legend has it, flogged members of the peace-loving religious group with a three-headed whip.

Eventually, Yuen connected his lineage to the Scottish Rawson family. It was smooth sailing from there. Conveniently buried in a Vermont graveyard were five generations of Rawsons, who were, in turn, descendants of four Mayflower passengers. Among these four were Richard Warren, who embarked on exploratory trips around Cape Cod, and William Bradford, governor and chronicler of the Plymouth Colony.

Left Behind

While Yuen could piece together his Puritan roots through Grandma Joyce’s tales and historical documents, he was stonewalled by his Guangdong relatives when he tried to reconstruct his Chinese heritage.

Delving into their family history meant dredging up memories surrounding the Japanese invasion and the Cultural Revolution — topics that older Chinese people don’t like to talk about. But alcohol, Yuen discovered, “gets that stuff out of them.” Over drinks, his Aunt Susan shed the stoicism and told him everything about how his family got out of China.

In the wake of the World War II Japanese occupation, China was crippled by political instability and a reeling economy. Seeking a way out, Yuen’s paternal family faced a difficult decision. Someone offered to squeeze them onto one of the last trains running from Guangzhou to British-occupied Hong Kong, but Yuen’s grandfather, Kwok Ming Yuen, whom he called “Yeh Yeh,” was out of town, caring for his own sick father, and unable to make it in time.

The family boarded the train. The border closed behind them, leaving Kwok Ming Yuen behind in Guangdong.

There, he operated a bus company, a modest business in which he oversaw 20 to 30 employees, Yuen said. But this branded him as a capitalist, one of the “class enemies” of the Cultural Revolution. In the 1960s, Mao called on the nation’s youth to purge capitalist and traditional values from Chinese society while embracing Communism. “Class enemies” were humiliated and beaten before crowds and later banished to rural re-education camps. As a business owner, Yuen’s grandfather was banished to the countryside for years.

His family, meanwhile, settled in New York City. Despite being half a world away, they doggedly worked up a chain of Chinese mainland connections, following one lead to the next until they reached someone who could secure Kwok Ming’s release. “Of course,” Yuen said, “they bribed a lot of people.” In the late ’70s, after nearly two decades of separation, Yuen’s grandfather made it to Brooklyn.

The Double Dragon

Yuen’s maternal grandfather, Jim Chung, also immigrated to the U.S. from Guangdong. He arrived in Vermont, where he met Joyce Robertson. “Gong Gong’s English was so bad,” Yuen said. “People thought he was speaking Chinese when he was trying to use English — but Grandma Joyce could understand what he was saying.”

Jim Chung and Joyce Robertson wed in the 1950s, flouting laws against marriage between people considered to be members of different “races.” They moved to Cape Cod in the 1970s, where Chung found work at the Dragon Lite in Hyannis, which was then owned by a relative. Business was good, but the scarcity of Chinese ingredients posed a challenge. Yuen’s family began growing their own bean sprouts.

Over time, Chung noticed that there wasn’t a single Chinese restaurant between Hyannis and Provincetown. And so, in 1978, he opened the Double Dragon in Orleans. One of the few places open until 2 a.m., the restaurant doubled as a lively drinking venue.

I had to ask what kind of cuisine Yuen’s grandparents served. Was it Cantonese staples? Delicate Chaoshan dishes, maybe? Or the Hakka flavors of my own heritage?

“It’s Chinese-American food,” Yuen replied. “My grandfather would’ve loved to have traditional food — but, come on, if you brought out a whole roast duck, with the head and all, nobody here is going eat it!”

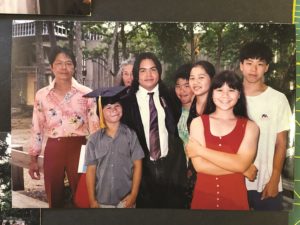

Yuen’s father, Steve, moved to the Cape from New York to work at the Dragon Lite, where he crossed paths with Yuen’s mother, Lida, the daughter of Joyce Robertson and Jim Chung. The family sold the Double Dragon in 2019 to new owner Udhdab Adhikari.

Though his genealogical research may be done, for Yuen, the question of how culture and ethnicity evolve remains salient — particularly as his generation starts its own families. One of his cousins recently had a child, who “doesn’t look Chinese at all,” Yuen said. “I mean, he’s got blond hair and blue eyes.”

And when Yuen was dating his Kara Wilson, who would become his wife, his cousins peppered him with questions about his relationship with a white girl.

“The biggest cultural difference is that my Irish wife doesn’t believe in meal planning,” he said. By 3 p.m., Yuen said, he is already thinking about what veggies to chop and when to fire up the rice cooker. “I guess that’s either the Chinese or the Puritan in me.”