PROVINCETOWN — The Outer Cape’s sparse population has long been part of its appeal. But during the early months of the pandemic, that characteristic of our towns suddenly became especially attractive. County-by-county data published by the U.S. Census Bureau on March 30 allow a look at whether some of the new neighbors who boosted the population between 2020 and 2022 have stayed, who they are, and what that means.

While the rest of the state has been undergoing what the Boston Globe in February called a crisis of “domestic outmigration,” losing a net 110,000 residents to other states (New Hampshire and Florida top the list), Barnstable County gained 6,729 new residents.

Statewide, that population loss makes it harder for businesses to fill jobs, posing an “existential threat” to the state’s economy and workforce, the article said.

The Cape gaining more people than any other county in the Commonwealth does not look like it will help the economy here much, however. What it reflects, said Mark Melnik, director of economic and public policy research at the UMass Donahue Institute, is “a lot of people taking respite on the Cape during the pandemic.”

To figure out how sticky those trends are going to be in the future, he said, policymakers have to try to sift “signal from noise.” The backdrop to the Cape’s apparent growth is that it’s nothing new: Barnstable County has seen year-over-year increases in domestic in-migration since 2005. And outmigration from the state has been trending negative for close to a decade in Middlesex and Suffolk counties.

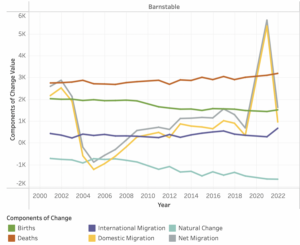

A closer look at the Cape’s gain reveals it is skewing perilously old. While most regions in the state have historically had positive rates of “natural change,” meaning the net result of births and deaths, Barnstable County has long had a negative natural change rate. With 3,298 births and 7,170 deaths, the Cape had a net decrease of 3,872 residents resulting from natural causes from 2020 to 2022. That is the largest natural population decrease of any county in the Commonwealth. And it brings the county’s population increase down to 3,453 when natural change and migration are combined.

Crucially, the county’s median age as of 2021 is 53.9 years, while the statewide median is 39.6 years, according to the Cape Cod Commission.

In other words, plenty of people are moving to the Cape. But as an already older-skewing population continues to age, there is legitimate cause for alarm about sustaining a critical workforce — and therefore any sort of economy — here.

“If you’re suffering from domestic outmigration and your average age is going up,” as is the case in statewide aggregates, “you end up hitting a wall where your economic growth is going to be really stagnant,” Melnik said.

With the real estate market so crunched by absentee ownership and environmental constraints, and an economy driven largely by low-paying sectors like tourism and hospitality, Melnik said he looks to the Cape “as a kind of microcosm” of the statewide crisis.

“If regular working folks can’t afford to live here, then you have a problem,” he said.

The Cape’s Seasonal Quirks

One of the demographic puzzles for the whole of Barnstable County is how to parse absentee ownership and part-time occupancy in the data. This is also true on the Outer Cape, which has the added problem of extremely small sample sizes.

In 2021, 43 percent of the homes on Cape Cod were secondary residences, while that number is closer to 60 percent for the four Outer Cape towns, according to Kerry Spitzer, a research manager at UMass Donahue. Spitzer helped coordinate the 2021 second-home owner survey for the Cape Cod Commission, which unsurprisingly found that usage days of second homes increased during the pandemic and that “the Cape continues to be a destination for folks who are looking to retire,” she said.

According to the Cape Cod & Islands Association of Realtors, 6,117 homes were sold in 2020 and 5,296 in 2021. A 2021 UMass Donahue survey of new homeowners also found that 35 percent of people surveyed were influenced by the pandemic in their decision, with the subfactors of increased remote work and outdoor recreation access playing a role.

Based on USPS change-of-address data, there has been a clear uptick in permanent moves to the Cape in the last two years. In 2020, there were a net positive 2,647 permanent address change requests to the Cape, compared to a net negative of 178 change requests the year before, said Sarah Colvin, communications manager for the Cape Cod Commission. But that number, which stabilized to a net positive of 231 in 2021, then turned back down to a net negative 909 change requests in 2022.

“There is no clear method to determine whether a change-of-address request comes from a transitioning second-home owner or a full-time resident,” Colvin said. “Overall, though, seeing a net positive in permanent address change requests into a town appears to point to an increase in permanent residents.”

Given the high number of absentee owners here whose primary residence is somewhere in Massachusetts, it’s also difficult to discern how that number fits in with the statewide domestic migration patterns that are raising alarm bells.

Spitzer said that, to her eye, the cause for concern on the Cape does boil down to housing. In-migration without a proportionate increase in housing stock exacerbates the high cost of housing on the Cape by definition, she said, and “there aren’t two separate markets for year-round and second homes. There’s just the real estate market.”

On the Outer Cape, where the share of absentee or part-time homeownership in the housing stock is even greater, Spitzer advised that all insights be taken “with a grain of salt” given the “bigger bands of uncertainty” in statistical analysis with a smaller sample.

And, as with the rest of the Cape, the question of seasonality is in play with address change data. Moves to the Outer Cape increase without fail in April, May, June, and July, then decrease in September, October, and November.

But taken together, the four Outer Cape towns, all of which have an even higher median age than the rest of the county, saw a net negative 481 permanent address change requests in 2022 and a net negative 220 in 2021, compared to a net positive 325 in 2020, according to USPS data collated by the Cape Cod Commission.

Eastham added the most permanent residents in each of those years and lost only three permanent residents in 2022; last year, Wellfleet lost 116, Truro 266, and Provincetown 73.