When David Smith steps hard on the treadle of his Chandler & Price 10-by-15-inch platen press, it begins to churn energetically, like a many-appendaged ocean animal. The press, built in Cleveland in 1905, is a beast of a machine — it weighs three-quarters of a ton. But it’s surprisingly quiet: the flywheel goes swish, the ink disk clatters softly as it spins, and the press speaks a gentle clank, again and again, as it pushes paper against type.

Smith hasn’t applied ink to the disk, so the platen press, for all its emphatic movement, isn’t actually printing. But he has inserted a “form” into the bed of the press. A form is like a puzzle: individual letters of type tucked into a frame, the words separated by spacing material ranging from tiny copper slivers to big blocks called “em-quads,” and secured by wooden blocks called “furniture” and by metal wedges called “quoins,” which are tightened using “quoin-keys.”

On a computer, choosing “flush right” or “centered” or “justified,” would do the trick of all those tools.

Smith has five letterpresses in his Wellfleet garage, ranging in size from this one to a very small cylinder press. He prints with these centuries-old contraptions strictly for fun, he says, though one sign on the wall of his workshop reads “Print Like You Mean It!” Another quotes Joseph Ames, the bibliographer and antiquarian who wrote a book on the history of English printing called Typographical Antiquities: “Souls dwell in printer’s type.”

Glowing orange in the light from large windows are stately cabinets, each full of cases of metal type: many hundreds of individual letters, numbers, and punctuation marks in different fonts: Helvetica 12-point italic; Palatino 18-point semi-bold; Craw Clarendon 36-point. “In the 1850s, or way back in the 1450s,” says Smith — the printing press was invented in 1440 by the German inventor Johannes Gutenberg — “you couldn’t just throw a switch” to change the font.

Most of the type is very small, separated by category — capital letters, lowercase letters, ones and fives, semicolons and commas. One case lies atop a cabinet. Smith says he has its compartments memorized, like the keys on a keyboard.

“What’s the most commonly used letter in the English language?” he asks. The answer is lowercase “e,” Smith says. He reaches for the largest compartment and pinches an “e” between two fingers. The “e” is backward (to print correctly, the type must be set upside down and backward). The least common letters are “z” and “j”; their compartments are very small.

There are two kinds of type, says Smith: wood and metal. The biggest piece of metal type that can be cast is 120-point, says Smith — bigger font sizes are made of wood, because the material weighs less. He hefts a 120-point “K.” It’s heavy and cold. (There are 72 points in an inch.)

There are actually two more kinds of type, Smith says. “The type you have, and the type you don’t have,” he says. “Yet.”

Some letterpress hobbyists suffer from “type envy,” says Smith. He’s not so afflicted — “I do lust over other people’s type,” he says, but he’s not as acquisitive as some.

Smith learned how to print with hand-set type at summer camp in the Berkshires when he was 14. The camp, which also offered activities like canoeing, sailing, and swimming, had a small printing shop. “They printed the camp’s menus,” he says.

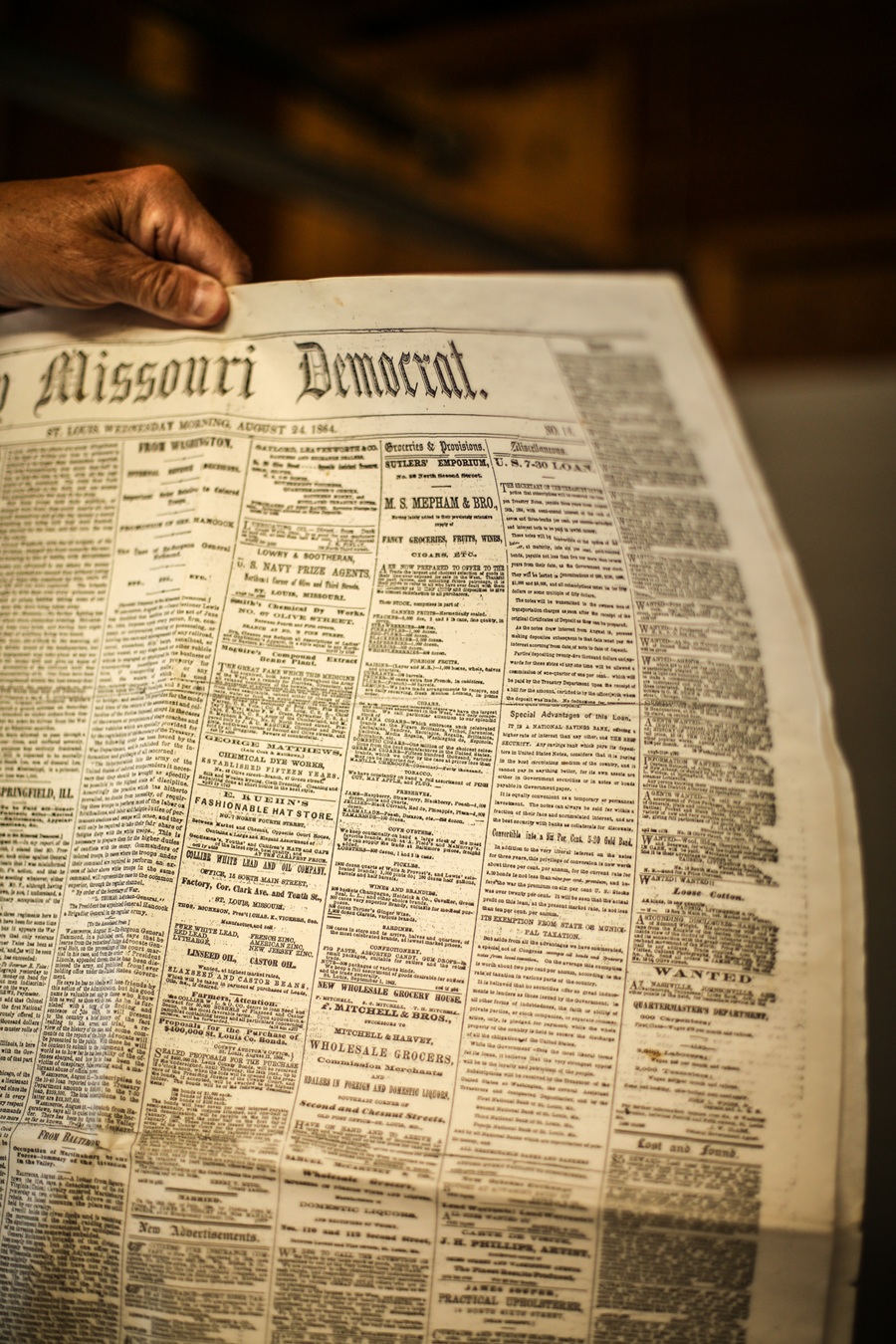

A couple of decades later, he got a job at the newspaper and printing office of an open-air museum in Des Moines, Iowa called Living History Farms. “I liked it so much that I wanted to acquire my own equipment,” he says. “So, I did, little by little.”

Now Smith belongs to the Amalgamated Printers Association (APA), a hobby group that has 150 members. The APA was founded in 1958 by two teenagers in Hastings, Minn., neither of whom had a printing press. They chose the word “amalgamated” — a synonym for “united” — from a thesaurus, according to the APA’s history page.

Every month, each member of the APA prints 150 copies of an item to be mailed to headquarters and then distributed to all the members: personal and professional announcements, poems, holiday cards. Smith’s material includes a statement about adopting his dog, Sadie, and an ornamental notice about his move to Wellfleet three years ago. “Once a month, you see what people have done,” says Smith. “It’s such a treat.”

He holds up a small piece of paper: a print made by Lisa and T.H. Groves of Prescott Valley, Ariz., APA #911. Smith’s number is 605. He calls his shop “Smythe Productions, Ltd,” a byline he’s had since middle school, when he taped record albums with a cassette recorder and distributed his homemade mixtapes to his friends.

Much of his equipment once belonged to another member of the APA, his friend Sky Shipley, who lives in St. Louis and casts new type from centuries-old molds. When Smith lived in Bloomington, Ind., he’d drive to St. Louis on the weekends to assist Shipley. “Rather than take my pay in cash,” says Smith, “he’d give me old equipment.” Then Smith would fix it up, good as — “well, used,” he says.

As a printer, he’s mostly self-taught. Although, he says, “luckily, with anything having to do with printing, there’s a lot of documentation. That’s just what printers do.” He’s got “a library of books” on how to set type, including high school manuals from the 1950s.

In a corner of the garage sits a mid-size cylinder galley proof press. Maybe the oldest in Smith’s shop, “it probably dates to the 1880s,” he says. On the cast-iron body of the press is forged the name “Miles Nervine.” Nervine was a doctor who sold “pain pills.”

A proof press, evidently, is meant to produce a proof “that you take back to the editor to see if everything’s spelled right and spaced right,” says Smith. Afterward, the copy would go to a larger printing press.

“Dr. Miles had this really bright idea,” says Smith. “He’d ship these to little country newspapers and give them to them with the arrangement that they’d put his ad in their newspaper for free.”

It’s the history of letterpress printing that fascinates Smith, along with the graceful architecture of each piece of individual type and the unceasingly tactile nature of the work.

Printers used to purchase type from foundries. Two foundry catalogs lie open on a table. One, for metal type, is from 1923. From it, a printer might order a set of type in the “Goudy Catalogue” font. In 72-point, the customer would receive three capital “A”s and five lowercase ones. In 24-point it would be eight capital “A”s and 16 lowercase.

The other catalog is from 1869, for wooden type. As Smith turns its yellowed pages, bits of the spine crumble and flake away. Smith’s favorite typefaces are the late 19th-century ones in this book, florid and decorative. “The more little ornaments, the better,” he says.

Smith has collected his catalogs over decades, often bringing them home from gatherings — called “wayzgooses” — with other printers. A printers’ fair is called a “wayzgoose,” says Smith, because of an old tradition in which the printer in a village would hold a feast for its workers and serve a roast goose.

When a group of printers gathers to produce something, that’s called a “chappel,” says Smith.

In the transition from letterpress printing to computerized printing — which happened for the New York Times in the 1970s — something has been lost, says Smith. Now, he says, “you type with your fingertips.” In his shop, “You’re moving metal around.” There’s a tangible atmosphere of permanence in the garage, present in the heavy materials of iron and wood and lead, and in the painstaking focus required to compose every word and align every column.

“Things are far more ephemeral now,” says Smith. But while the paper he prints won’t last long, the presses themselves will. He and all other printers are “temporary custodians,” he says, of their equipment. “This stuff here, it will outlast me. It’ll outlast my kids.”

He’s not sure what will happen to the presses, the cases full of type, the cabinets and catalogs and specialized tools, after he’s gone. “The most important thing,” he says, “is to let somebody else have it and use it.”