David Maril lives year-round in the house on Bradford Street in Provincetown where his father, Herman Maril, painted every summer from 1958 until his death in 1986. David winterized the house three years ago after retiring from a 35-year career in sports journalism. He now manages his father’s legacy, with the house serving as an ad-hoc museum, gallery, and storage space.

“When my parents got married in 1948, they honeymooned in Provincetown,” says David. “At first, they rented a place on Pearl Street. He’d set up an easel and paint outside. My mother thought it was the most beautiful place she’d ever been. They came every summer after that. They were hooked.”

The couple bought the Bradford Street house in 1958 as a summer residence. The other nine months of the year, Herman taught at the University of Maryland in College Park. He, his wife, Esta, and their children, David and Nadja, lived in Baltimore.

The 1830s structure was originally the Long Point Post Office before it was floated across the harbor at the turn of the 20th century. “This was the post office window where Long Point residents would line up for their mail,” David says, pointing to a small square pane of glass in the living room. “It’s the only original window left in the house.”

Herman’s paintings line the walls of the narrow, steep, “not-exactly-friendly” stairs that lead to the second-floor studio. The studio faces away from the street to catch the east light through one large window. The roof has been raised a couple of times, with the wonky pitch of the floors never corrected.

The studio is small. To the left of the window, David has kept his father’s workspace as he had it set up: old coffee cans full of brushes, tubes of paint piled in heaps, a marble palette with dried paint pushed to the edges.

“This part hasn’t changed,” says David. “This is where he painted. I remember he always had classical music on.” Above the palette, there’s an early self-portrait from 1929, made just after graduating from the Maryland Institute of Fine Arts, that Herman kept as a talisman.

To the far left is an easel with a framed, finished painting in Herman Maril’s signature style. He pared his surroundings down to their essential abstract components — a hitherto unnoticed corner of a room, the shoulder of a chair, the roll of the dunes, the arc of the bay.

“My father knew a lot of the artists here because he was showing in New York galleries from the late ’30s on,” says David. “He was good friends with Karl Knaths and Milton Avery. They would all alternate studios. At the end of the summer, they would visit each other and show off their work.” David, who was seven or eight at the time, recalls Avery as a “very quiet, low-key type of person. Friendly, but not real outgoing.”

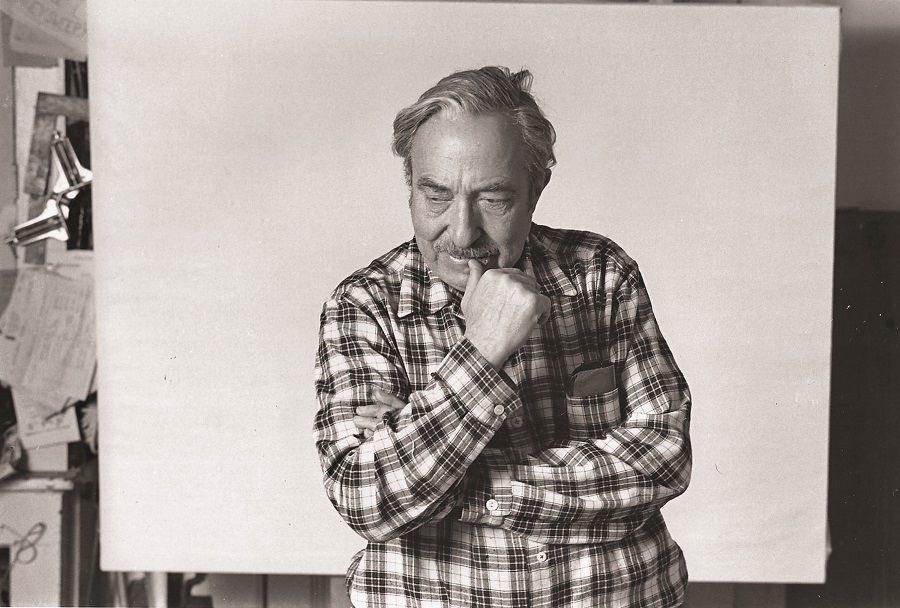

Hanging on a peg to the right of the studio window is Herman’s favorite plaid shirt. This same shirt can be seen in a photograph of Herman by Aaron Levin that also hangs, framed, on a studio wall. In another corner of the room sits a simple, rather unassuming wooden rocking chair.

“That was Mark Rothko’s studio chair in Provincetown,” says David. “Rothko gave it to my father when he sold his Provincetown house.” David remains friends with Rothko’s daughter, Kate.

Next to the entrance to the studio, there’s an old Bakelite rotary phone and a row of wood planers. “These are artifacts that he liked,” David says. He has even kept a tall, charred piece of wood that Herman scavenged from the street and secured on a pedestal. What attracted Herman to it still perplexes David: “I think he just liked the way it looked,” he muses.

“One thing that I learned from my father — and it took me a while to recognize and understand it — was his ability to take out, in his mind, what the clutter was,” continues David. “His words stick with me: ‘I don’t wait for inspiration. I paint every day, and inspiration comes with work, with painting,’ and that’s true.”