“Our houses are our biographies, the stories of our defeats and victories,” wrote Mary Heaton Vorse in Time and the Town, her memoir of early 20th-century life in Provincetown.

Vorse’s own biography was voluminous: over the course of her long life, she was a journalist, suffragist, social and labor activist, feminist, novelist, and parent. Similarly, the house at 466 Commercial St. that she bought in 1907 and lived in for six decades passed through several stages in its history. The home of a prosperous sea captain in the mid 19th century, it became the locus of the town’s art and literary scene under Vorse’s stewardship before deteriorating into a neglected eyesore after her death in 1966. Sensitively restored by designer Ken Fulk in 2020, it is now the home of the Provincetown Arts Society — and once again an incubator for cultural life here.

In a remarkable new body of work concurrently on view at the Vorse house and at Schoolhouse Gallery (494 Commercial St., Provincetown), photographer David Hilliard extends Vorse’s cultural legacy into the present. “What’s Done in Shadows” comprises portraits of about two dozen members of the Provincetown community — “an eclectic cast of long-term Provincetown residents, summer workers, artists, writers, performers and other social orphans,” as Hilliard says in a statement accompanying the show — taken in and around Vorse’s former home. Most of the subjects are women or “have a connection to the feminine,” and all are Hilliard’s partners in the creation of what he calls his “collaborative tableaus.”

“The photos are based loosely on Vorse’s life as a freedom fighter, activist, and advocate for women and the disenfranchised,” says Hilliard. And the house itself is as much a subject of the series as the people shown in it. “I’m interested in both the skin of the original house and the objects that are now in it,” he says. “So, there’s a bit of Ken Fulk in these pictures, too. And of course, there’s a lot about me in them. In any given image, there are several different histories working together.”

Prominent figures in Provincetown’s cultural landscape are depicted in different rooms. Actress Gail Strickland appears in one of the most arresting images: posed in the kitchen amid produce grown in its garden, Strickland fixes the viewer’s eye with a gaze as sharp as the distractingly large butcher knife she wields.

Hilliard’s portrait of gallerist Berta Walker captures its subject in a more genial mood: bathed in sunlight and surrounded by flowers, Walker radiates warmth as she soaks her feet in a bubble-filled washtub. The photograph’s title — Berta Insists on a Smile — provides insight on Hilliard’s collaborative nature.

“The idea for the portrait sort of snuck up on us,” he says. “I told her, ‘Let’s try to make a narrative. You’re a hard worker. Let’s show you in a moment of repose.’ She loved it. She had on a big smile the whole time. I asked, ‘Can we do one where you’re not smiling?’ But in the end, the pictures of her smiling really were the best ones. She didn’t look like herself without a smile. I think she knew that, so she was insistent about it. I couldn’t name it anything else.”

Hilliard’s rapport with his subjects is an extension of his familiarity with Provincetown and its denizens. “I grew up coming here; I came out here; I experienced the AIDS epidemic here,” he says. His background in film and fashion are apparent in the narrative quality of his photographs and their emphasis on the way his subjects present themselves. “I was a film major for a hot minute, but I was told my work was too static,” he says. “And fashion didn’t work out either. So, I started taking pictures. Everything coalesces in a photograph.”

The precise compositions and formal intricacy of Hilliard’s photographs suggest careful planning and forethought. But while he says he considers what a finished photograph will look like before he takes it, he allows for improvisation and responds to the variables he encounters during a shoot. That open-endedness is responsible for many of the serendipitous details in the images.

Strickland arrived for her session with strands of gold thread in her wig, their subtle sparkle apparent only upon close inspection of the print. Ingrid, Prepared, a portrait of Ingrid Mattis-Walker, is another example of how Hilliard incorporates his models’ choices into the portrait they produce together. “It wasn’t a rainy day or particularly cold, but she showed up wearing a trench coat and brought two of her Bibles,” he says. “So, I included an umbrella we found to tell the story that she was prepared for anything. These things are like gifts. You don’t expect them, but they become an important part of the picture. There are gifts everywhere. I can’t collect them fast enough.”

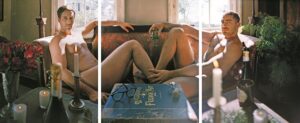

Hilliard references the experiences of his subjects in other ways. “All the pictures are inspired by conversations with people,” he says. “I make the pictures for them. I’m always listening to my subjects to come up with ideas for their photographs. I was talking to one model about the rituals he shared with his partner, and he said that sometimes on weekends they enjoyed two bottles of champagne together.” Hilliard had them pose on a lounge in the parlor at the Vorse house with two bottles on the table in the foreground. The photograph is called Two Bottle Morning.

Part of the power of Hilliard’s portraits lies in the relationship they create between subject and viewer, usually centered on direct eye contact. Packards Distracted, one of the few group photos in the series, is an exception. “I met Cynthia Packard, and we had a great conversation about the project,” he says. “She told me she wanted to bring her whole family — four kids and her husband in this tiny kitchen. They were all distracted, and we only had about 10 minutes to make the picture. I went with it and told them to all look in different directions except for the man on the far right, who was very still and focused the whole time. In a way, it’s really a portrait of him.” The composition lends the photograph tension and mystery as we surmise the cause of its subjects’ anxiety.

There are elusive narratives in photographs where no human subjects appear at all. Intermission depicts the courtyard of the Vorse house at twilight, empty of visitors. “It’s a portrait of the presence of absence,” says Hilliard. “The three chairs are a reference to Henry David Thoreau: ‘I had three chairs in my house; one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society.’ ”

Hilliard uses a four-by-five large-format camera and composes each image in the viewfinder itself, with minimal if any cropping after they are printed. “I like that challenge,” he says. The format produces images with an expansiveness that belies the size of the rooms in which the photos were taken; after looking at the Schoolhouse Gallery half of the exhibition, it comes as a shock to wander down the street and see how small the rooms in the Vorse house really are. While Hilliard’s photographs are usually printed large with each frame individually mounted on its own support, the photographs in “What’s Done in Shadows” are presented in an assortment of scales and formats. Some are conventionally framed, while others are tacked to the walls.

“I wanted things to look like an artist studio, something ethereal,” says Hilliard. “I love experimenting with presentation.”

Viewed as a whole, the series creates a powerful dialogue with Vorse herself, who emerges as a mostly unseen but guiding presence. “I hope that collectively my photographs begin to represent a complex community that she would have enjoyed sharing dinner with,” says Hilliard. They also represent a more inclusive community than the one Vorse was part of during her lifetime. A young mixed-race couple share a chastely intimate moment in a photograph taken in one of the house’s bedrooms; in another, taken in Vorse’s own bedroom, a tangle of figures of diverse sexualities and gender identities embrace on a bed, while two people stand sentinel on either side, and a portrait of Vorse watches from the wall.

It’s difficult to imagine any of these present-day guests in the Provincetown of a century ago. But given her progressive bona fides, says Hilliard, “I think Vorse would have loved it.”

What’s Done in Shadows

The event: Vignettes from the Mary Heaton Vorse house: new photographs by David Hilliard

The time and place: Through July 19 at Schoolhouse Gallery, 494 Commercial St., Provincetown, and through Aug. 19 at Provincetown Arts Society, 466 Commercial St.

The cost: Free; see schoolhousegallery.com for information