PROVINCETOWN — The Massachusetts branch of Curaleaf, the world’s largest cannabis company by revenue, is suing the town over claims that it improperly collected community impact fees from the company’s dispensary on Commercial Street. The company seeks to recover $372,260 paid to Provincetown from 2020 to 2022.

In a complaint filed in Barnstable County Superior Court on Nov. 5, 2024, Curaleaf argued that the town violated its contract with the dispensary by collecting the fees without showing how they were “reasonably related” to the business’s local impacts on the town, such as through increased spending on inspections, law enforcement, or other costs associated with the public health effects of marijuana.

Provincetown denied those allegations in court filings on Jan. 17, arguing that Curaleaf had breached its contract, called a host community agreement, by failing to submit sales and financial records on an annual basis. Under its original agreement, Curaleaf was supposed to pay fees at the agreed-upon rate regardless of documented impact, the town said.

Curaleaf disputed Provincetown’s claims in subsequent court filings in February and March.

The Provincetown suit is one of a string of similar lawsuits across Massachusetts. In January, the town of Haverhill agreed to a settlement giving $612,500 to cannabis dispensary Stem, which had sued in 2021 because Haverhill had not provided a justification for its impact fees.

A similar lawsuit in Uxbridge was settled in 2024, with the town paying $1.2 million to Caroline’s Cannabis — about 93 percent of what the dispensary had sought in its complaint.

Curaleaf’s original host community agreement with Provincetown was signed in 2018 and did not specify whether impact fees had to be “reasonably related” to local costs. But the dispensary is citing a state law passed in July 2022 that overhauled and largely eliminated community impact fees. The bill, which passed unanimously in the state Senate and by a vote of 153 to 2 in the House, forbade towns from collecting impact fees as a percentage of sales and allowed licensees to sue towns for breach of contract. The bill left in place the 3-percent local option tax on marijuana sales that is levied by Provincetown and nearly every other town with a retail dispensary.

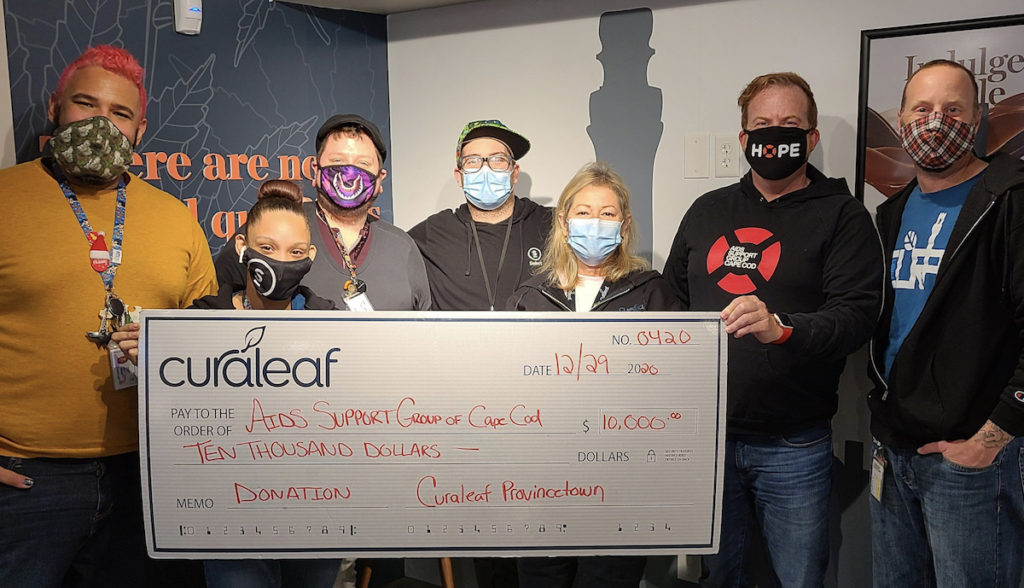

After then-Gov. Charlie Baker signed the law, Provincetown stopped collecting impact fees and Curaleaf stopped reporting sales figures, according to court filings and the town’s public records of marijuana revenue. By that point, the dispensary had paid quarterly impact fees on all its sales from the time it opened in January 2020 until the end of March 2022. The money went to the town’s general fund and was used for operating expenses, including police, fire, and health dept. expenses, according to Town Manager Alex Morse.

1,000 Contracts

“I think what you’re seeing in this Provincetown case is one of these legacy contracts that got signed, probably on the earlier side,” said Jeffrey Moyer, a public policy professor at Northeastern who specializes in Massachusetts cannabis policy. Contracts signed soon after legal marijuana licensing was formalized in 2017 are often “out of sync with the current regulatory environment,” he added.

As municipalities renegotiated their agreements with dispensaries after 2022, the new rules “created a lot of uncertainty for the towns,” said Elizabeth Lydon, a lawyer at Mead, Talerman, and Costa.

Lydon has negotiated host community agreements on behalf of over 30 towns. “Municipalities were not documenting costs because their agreements said that they didn’t have to, that they understood that there were unforeseen costs,” she added.

Both Curaleaf and Provincetown have requested a trial by jury. The latest court action was on April 24, when the parties filed a joint motion to consolidate the case with two other lawsuits filed by Curaleaf against the towns of Ware and Oxford, where its two other Massachusetts dispensaries are based.

Provincetown is represented in the case by KP Law, which also represents Ware and Oxford.

Neither Curaleaf nor its attorneys responded to requests for comment, while Morse said he could not comment at length. “We believe the Town’s response to Curaleaf’s claims speaks for itself,” he wrote in an email.

Moyer said that the legislature “didn’t necessarily intend for dispensaries to be able to claw back those funds” when they passed the 2022 reform.

The Mass. Municipal Association had vigorously opposed those reforms and responded to inquiries from the Independent with a statement from its executive director, Adam Chapdelaine.

“Municipalities across the Commonwealth entered into more than 1,000 mutually agreeable contracts with businesses as part of the establishment of cannabis commerce in Massachusetts,” wrote Chapdelaine. “Challenges to duly executed contracts will have a chilling effect on the industry, as municipalities will not have the trust needed to engage with cannabis businesses.”

Not Every Dispensary

Curaleaf is the oldest of Provincetown’s four active dispensaries and the only one that has sued to recoup its impact fees thus far. Being the first dispensary on Cape Cod helped it register a banner first year of sales: its impact fee payments to the town indicate that the store had $7.3 million in sales in 2020.

As other stores opened in Provincetown, Wellfleet, and Eastham, however, Curaleaf’s payments to the town decreased dramatically before ending in 2022.

Statewide, the growth of cannabis sales has slowed, according to CCC data. “I wouldn’t necessarily call it a full recession, but there’s definitely a flattening out,” Moyer said.

The amount that some companies paid in 3-percent impact fees is significant and potentially worth fighting for, Moyer said. “That’s not chump change for one of these dispensaries — that’s a significant amount.”

While the scale of the recent settlements in Uxbridge and Haverhill have “emboldened” some establishments to litigate, Lydon said, there have been other lawsuits in which cities have collected money from dispensaries instead of the other way around. In another Haverhill case, the dispensary Full Harvest Moonz paid the town $250,000 in a settlement last September.

Moyer said that smaller businesses or those “with close connections to the local community” are often less inclined to seek costly litigation against the town.

Lydon agreed. Many cannabis businesses “don’t want to get tied up in litigation,” she said. “They just want to continue doing business.”