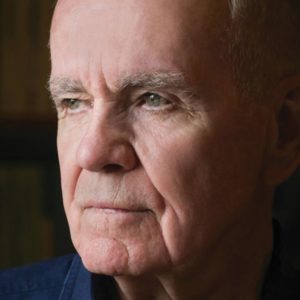

Cormac McCarthy’s novels like Blood Meridian, his 1985 story about twisted characters annihilating one another in a mythic American West, reveal a smart, dark view of humanity.

Now 89, McCarthy has won the Pulitzer Prize and was a MacArthur fellow, so it’s fair to say that anything he publishes at this point will garner attention. A devoted admirer of his writing, I couldn’t wait to read The Passenger. Released in October, it was McCarthy’s first novel in 16 years.

John Jeremiah Sullivan, writing in the New York Times, gave The Passenger high marks. He described the book as “portentous.” But as I finished the novel, a different word came to mind: pretentious.

McCarthy’s novels take place in the past (The Border Trilogy), the present (No Country for Old Men), and a dystopian future (The Road). Most of them are set in Texas and Mexico. His characters wrestle with inner and outer demons. They include a runaway teenage horse whisperer making his way into Mexico and an aging sheriff making sense of the terror and violence narcotraficantes inflict on his community. The spare dialogue and exciting plots of several of these novels are cinematic, and several of them have been adapted for film.

Readers will find many of these attributes in The Passenger. But in this novel time shifts and swerves, and narratives switch between two principal characters.

Readers won’t have much of a clue where either narrative is going in the early parts of the book, and they may continue to scratch their heads as the book unfolds. In one narrative, tormented main character Bobby Western wanders through Louisiana, Tennessee, Oklahoma, Mexico, Ibiza — and his own past. He is McCarthy’s version of The Most Interesting Man in the World, an intellectual Hemingwayesque man of action: deep sea diver, Formula 1 race car driver, mathematician, physicist.

In the other narrative, set in italics, Western’s sister Alicia converses with hallucinatory characters originating in her schizophrenia. McCarthy slowly reveals that Alicia killed herself, and that she and her brother were in love. (In The Passenger, Alicia is the minor character. In its companion novel, Stella Maris, published on Dec. 6, McCarthy focuses on Alicia’s conversations with her psychiatrist at the hospital where she lived before taking her own life.)

Have I given away too much of the story? Not really, because The Passenger is a departure from McCarthy’s more accessible novels in which plot and character development are central. Readers meet Western as he and a dive crew explore a private jet submerged off the coast of Louisiana. A passenger is inexplicably missing from the plane. Western wonders about the missing passenger, but not for too long. McCarthy drops the mystery as he explores metaphorical passengers traveling through a philosophical space-time continuum as well as psychological and mystical realms.

It’s almost impossible to summarize the plot of The Passenger. Imagine a summary of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick: “Ishmael, a man who can’t get along with others, ships out on a boat helmed by a one-legged captain obsessed with a white whale. This captain catches the whale but dies in so doing.” It sounds straightforward. But the summary mostly misses the point of the novel’s 135 chapters.

Here’s an example of McCarthy’s examination of the theme of understanding what it means to be a passenger. In it, Alicia converses with her main hallucinatory character, the Kid, a very small man with flippers for limbs who responds in spoonerisms, playful phrases, and slippery answers. Alicia asks the Kid how he arrived (in her mind, in her room). He tells her he arrived by bus.

As is his wont, McCarthy eschews punctuation marks and attributions in dialogue. Alicia is the first speaker, below:

Could they see you?

The other passengers?

Yes.

Who knows? Jesus. Probably some could and some couldn’t. Some could but wouldn’t. Where’s this going?

Well what kind of passenger can see you?

How did we get stuck on this passenger thing?

I just want to know.

There are scenes of human and nonhuman passengers throughout the novel. In one, Western tells a woman on a bus that his destination is the end of the road. In another, McCarthy summons the image of migrating birds, with Western wishing “[t]hat none disturb these passengers.” This may be as close as McCarthy comes in the novel to expressing his world view.

There are undoubtedly readers who will enjoy watching this celebrated old lion of literature noodle his way through references to what used to be called “the canon”: Faulkner, Shakespeare, Eliot, and others. A brother unhealthily involved in the life of a troubled sister? The Sound and the Fury. We get it.

But it’s been a long while since I read a book asking me to look up words. Hoving. Ectromelic. Knurled. Heresiarch. Does McCarthy incorporate such words because they are meaningful to him and please him? How many readers will be curious enough to look up the possible significance of the date Western walks up a street in New Orleans?

It’s not that I’m disappointed that McCarthy has gotten less accessible. I respect his mind and am glad to have another opportunity to watch him work. But I am less patient these days with literary insiderism. I doubt I’ll read Stella Maris because I don’t really want to explore the mind of a brilliant, tormented young woman who kills herself.

I want to read novels like Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower, the tale of a ferocious young woman of color who moves along an apocalyptic road recreating the world in her own imaginative and practical image. I feel sad when I realize that while I was reading McCarthy’s Border Trilogy I’d never heard of Octavia Butler.