Comics artist and writer Phil Jimenez was alone a lot when he was growing up in Long Beach, Calif. “Drawing was a way to entertain myself,” he says.

Known for his work on Wonder Woman, New X-Men, Infinite Crisis, and The Invisibles, Jimenez has a new book coming out this summer. The autobiographical story, Spaces, will be part of the DC Comics Pride anthology.

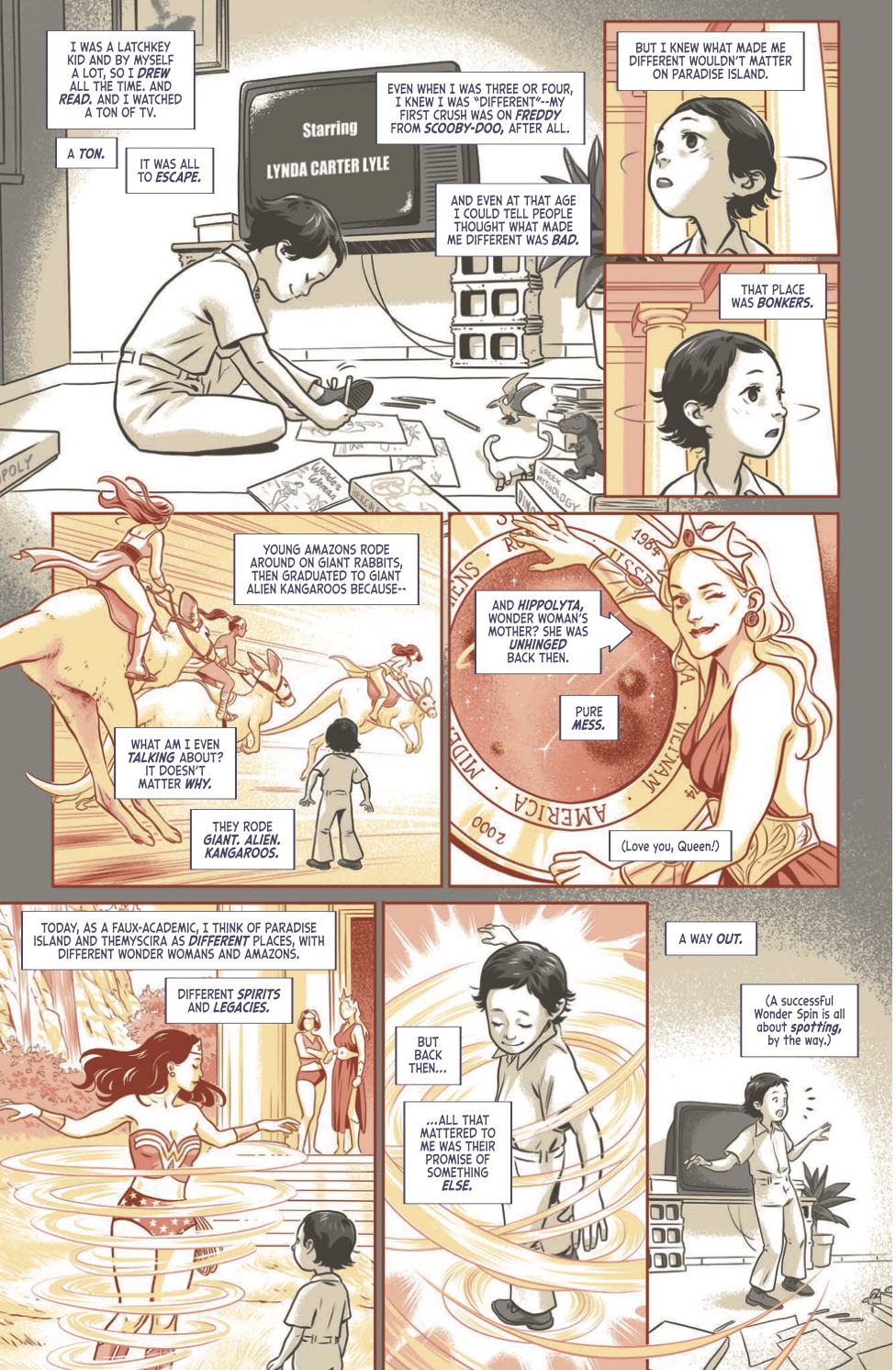

Jimenez was the writer for Spaces while Giulio Macaione was the artist. The story rewinds to Jimenez’s childhood as a boy mesmerized by fantastical spaces. “Museums and theme parks, renaissance fairs and movie studios, roadside attractions and wild-animal parks, castles and mansions and aquariums…” he writes. The boy in the story dreams of being adopted by a group of Amazons living on Paradise Island.

“All that mattered to me was their promise of something else,” writes Jimenez, “a way out.”

He lived with his mother in a Long Beach apartment project. She worked for GTE, the phone company. She was a talented artist and encouraged his art, though, according to Jimenez, her parents hadn’t allowed her to pursue her own talent because she was a woman. Years later, after she died of cancer, he found she had quietly continued painting and drawing. He keeps one of her paintings framed on the wall of his apartment.

When his mother was at work, he says, “I watched TV shows and read a ton of books. I was in love with storytelling. Any show with a cliffhanger really got me.”

He would watch TV shows like Land of the Lost, then take a stack of paper and redraw the scenes over and over from beginning to end. “I was interested in narrative,” he says. “I didn’t have language to talk about what I was doing, but I was tracking storytelling and plot and recreating that on paper.

“Part of it was just being a closeted gay kid and wanting to be anywhere else but my tiny Long Beach apartment,” he continues. Imagining magical spaces on paper was his way out. “I couldn’t actually build them, but I could still draw them, make them, and inhabit them.”

He is still fascinated by the imaginary places children create. “They’re called paracosms,” he says. “Often gay kids do it as places of escape — they’re highly elaborate fantastical imaginary worlds with all sorts of rules and guidelines.”

At 19, Jimenez left California for New York to start college at the School of Visual Arts. When he got to the city, he called the office of DC Comics to see if editor Karen Berger would meet with him. She allowed him to come up to her office with his portfolio, where, according to Jimenez, she told him it was terrible.

After sophomore year, Jimenez ran out of money and had to drop out of college. But just as he was returning to his mother’s, Neal Pozner called. Pozner was the talent coordinator at DC at the time. He had seen Jimenez’s portfolio.

“You can’t draw,” Pozner told him, “but you’ll learn to draw on the job.” Pozner told Jimenez that many young artists are more interested in drawing that one amazing panel of a superhero than they are in telling a story from panel to panel. “What you can do is tell stories in pictures,” Pozner told him. “You understand narrative.”

Pozner hired him that summer of 1991. Jimenez has worked for DC Comics ever since.

That July, Jimenez went to the Comic-Con convention in San Diego and met Pozner in person. “I had this huge crush on him,” says Jimenez. “And then because I was young and didn’t know any better, I got it in my head that I would ask him out on a date.” Jimenez was 21 and Pozner was 36.

Pozner agreed to the date. But not without trepidation, Jimenez says. There was the age difference, the work relationship — and then there was the fact that Pozner had AIDS.

“We went on our first date to the Met, which was extraordinary,” says Jimenez. “We spent the next year and a half together.” Pozner died in 1994.

No one at DC Comics knew Jimenez and Pozner were a couple. But the rabbi at Pozner’s funeral thanked Jimenez for taking care of him. “I can still remember the silence in the room,” Jimenez says. “That was my official coming out” — one he found humorous.

A couple of years later, Jimenez wrote The Tempest, a comic book tribute to Pozner. Jimenez came out publicly through the story, which made him the first mainstream superhero comic artist to do so. Jimenez says there were underground comics in the independent world, but in the superhero realm people were not public about being gay. Jimenez was nominated for an Eisner Award for The Tempest in 1997.

Jimenez moved to Provincetown two years ago. “What draws me here is the promise of the place as I see it,” he says, “which is not always realized, but it feels like the components are all here — the land, the geography, the spirit, the people. The actual size of Provincetown — geographically tiny and architecturally dense. We are clustered here together, which forces a degree of interaction that you might not have in other spaces.”

Jimenez vacationed here for 25 years before making it his home. “It was the one place I wasn’t worried about being attacked or threatened for being gay,” he says. “That part of your brain can relax a bit here. In an unstable geopolitical environment, I think places like this are important.

“I’m afraid of the rapid gentrification of this place and the evaporation of these attributes,” Jimenez says. He is a proponent of fun and frivolity as political acts. “We need to maintain places where revelry is an act of defiance,” he says.

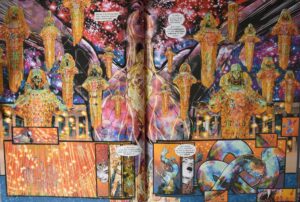

Jimenez won the Eisner Award in 2022 as the Best Penciller/Inker for Book One of Wonder Woman Historia for the DC Black Label. Critical accolades and awards have piled up through the years of his career in comics, but as he writes in Spaces, “I just know all these folks who created fantastic worlds made the real world safer for me, bigger for me, and made me want to do exactly the same.”