PROVINCETOWN — The unnamed winter storm that dumped heavy rain on the East Coast on Monday, killing two people in Massachusetts and one each in New York, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina, caused a fresh round of coastal flooding in Provincetown’s East End. The storm came almost exactly a year after Winter Storm Elliott sent an even larger surge of seawater into the same areas on Dec. 23, 2022.

Coastal Flooding

INUNDATION

Maps Foretold Two Coastal Flooding Events in Provincetown

Detailed data show where seawater might flow

PROVINCETOWN — The historic district here has been underwater twice in just the last five years. The first flood came when the nor’easter of Jan. 4, 2018 caused seawater to flow like a river down Gosnold Street and form a three-foot-deep pool on Bradford Street, soaking the basement of town hall and dozens of nearby homes and businesses.

This past Dec. 23 was like a Hollywood sequel, with the same basic plot at a new location. Provincetown Harbor was whipped into frothy waves by winds from the southeast, sending seawater under and around homes on Commercial Street’s East End, down Daggett Lane and Howland Street, and again forming a pool on Bradford Street. Businesses, houses, and especially basement apartments were flooded, and many people who lived in that area are still displaced, either looking for new homes or waiting for repairs.

What these floods had in common, besides their apparent affection for Bradford Street, was that their pathways were foretold. Both storms pushed seawater on routes that had been precisely mapped by local geologists.

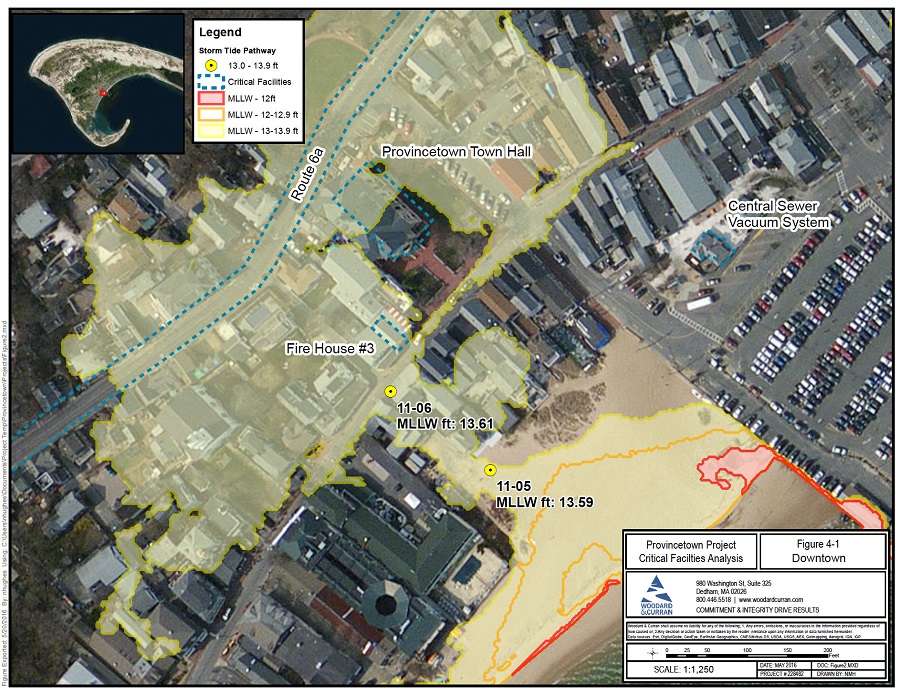

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) prepares flood maps for the whole country, but since June 2016 Provincetown has had much more detailed maps of its flood pathways, created by a team of scientists at the Center for Coastal Studies (CCS).

The storm tide pathways predict where water might flow if the height of water in Provincetown Harbor reaches various benchmarks above the mean lowest low tide line. The maps are built on a type of extremely fine-grained elevation data from the federal government called Lidar, which are collected from lasers mounted on airplanes, said Mark Borelli, head of marine geology at the CCS and the lead scientist on the mapping project.

“The experimental datasets were published around 2005, and then after Hurricane Sandy in 2012 we started getting really good data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration,” Borelli said. “It’s so useful for so many different things, and the information is public.”

Borelli’s team took NOAA’s data from 2014 and validated certain elevation measurements with even more precise global positioning systems.

“Our GPS is science-grade, so the accuracy is within two inches,” Borelli said. “We were mapping street by street in Provincetown.”

By June 2016, Borelli and his colleagues Steve Mague, Theresa Smith, and Bryan Legere had visited 81 potential flood pathways in Provincetown, 72 of which turned out to be possible routes for salt water. Many of them are clustered together, such that seawater in some neighborhoods has a dozen points of entry.

But the mapping showed that some of Provincetown’s most important geographies were threatened by only one or two specific channels. The Gosnold Street pathway was one of them, and it wound up funneling seawater onto Bradford Street and into town hall only 18 months after the scientists published their work.

That Jan. 4, 2018 storm was much worse than forecast, Borelli said. The winds were from the northeast that day, which meant huge waves were slamming into the National Seashore at Race Point Beach but none were rolling into Provincetown Harbor. Even without waves, however, the atmospheric pressure dropped so low that the harbor rose nearly a foot above the National Weather Service’s storm surge forecast to 15.4 feet above the low-tide line, Borelli said.

That was enough to put the Gosnold Street pathway under about seven inches of flowing water. At least two other pathways that Borelli’s team had identified also flooded, near Captain Jack’s Wharf and the Delft Haven cottages in Provincetown’s West End. Other communities up and down the East Coast suffered coastal flooding as well in the “bomb cyclone” that the Weather Channel informally named Winter Storm Grayson.

“I’ve never seen an accounting of what that storm cost in Provincetown,” Borelli said. “We know about the two fire engines the town had to replace, but the insurance companies don’t like to talk about how much they paid out to homeowners, and that’s private information.”

If the town had an estimate of the total cost of that storm, it might have been easier to move more aggressively toward coastal defenses, Borelli said.

The Gosnold Dune

After the 2018 storm, Provincetown began working to install a coastal dune to block the Gosnold Street flood pathway. A “taking” by eminent domain of the beach access rights needed to build and maintain the dune was authorized by town meeting voters in September 2020. The town developed and submitted a grant proposal to FEMA in 2021 that the state government believed would win federal funding, Provincetown’s community development director Tim Famulare told the Independent last month.

That application was for almost $3 million because it paired the construction of a flood-protection dune at Gosnold Street with a relocation of the Ryder Street stormwater outfall drain at the same location. FEMA surprised many state and local governments that year by choosing to fund only very large projects, Famulare said. Provincetown’s $3 million proposal was too small to make the cut.

“At that point, we didn’t want to hold up this project any more,” Famulare said. The town voted to fully fund the construction of the dune at Gosnold Street at town meeting in 2022 at a cost of $450,000. The town received a state grant last fall for $80,000 to defray final design costs.

Every time a major storm surge has been forecast since 2018, the DPW has built a three-foot-high berm of sand across the Gosnold Street pathway as well as at the Court Street landing and the town landing at 111 Commercial St. The Gosnold Street pathway has not flooded in the five years since. But the dune itself is still not under construction.

The complex legalities regarding the land under the dune have been the biggest difficulty, Famulare said. Eminent domain takings can be challenged in court, and it is not clear how much the town should pay for the easements that are needed to proceed.

Borelli said the timeline was not unusual but was still a worry — and the dune at Gosnold Street is the closest thing to a slam dunk that Provincetown is ever likely to see.

“In a lot of coastal situations, you don’t know what the right thing to do is,” Borelli said. “In this instance, we know a dune is the right choice: the regulators, the politicians, the public are all in agreement.”

The December Flood

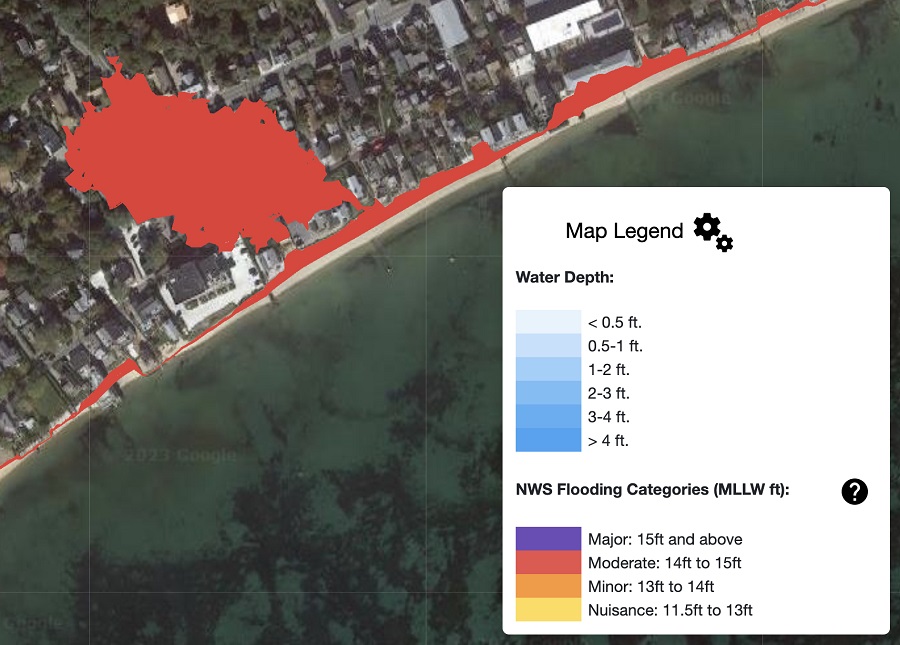

Almost exactly five years after the 2018 storm, an unusual-for-winter sou’easter hit this past Dec. 23. It produced a smaller storm surge in the harbor but nonetheless managed to flood three more of the storm tide pathways that Borelli and his team had mapped in 2016.

The most severe flooding was at Howland Street and Daggett Lane, where salt water flowed across Commercial Street and all the way to Bradford Street. There were also floods north of Commercial Street around Suzanne’s Garden and near the Coast Guard station in Provincetown’s West End.

The flooding was localized to Provincetown, however. That storm, which the Weather Channel informally named Winter Storm Elliott, brought extremely low temperatures to much of North America and huge amounts of snow to the Great Lakes but did not cause widespread flooding along the New England coast.

Borelli and Mague walked the harbor and the streets in Provincetown’s East End after the storm, looking for indications of the pathway the floodwaters had followed.

“Our big question was, why these particular pathways, and why didn’t they flood in 2018?” Borelli said. The harbor had risen to only 13.8 feet above the low-tide line during Elliott — almost two feet lower than in 2018 — and other pathways further east and west of Howland Street did not flood.

Borelli had entertained a theory that some unusual fluid dynamics had sloshed the harbor’s incoming tide directly toward the flood pathways near Howland Street, he said. (The splashing of breaking waves does not generate nearly the volume of water required to flood a neighborhood, he added.)

His walk with Mague led him to a different theory.

“This is just a hypothesis, but some of the houses that have been lifted up — there’s one near Howland Street and another near Suzanne’s Garden — we think the ground there is lower now than when we measured it in 2016,” Borelli said. “These houses had to be lifted. It’s a National Flood Insurance Program requirement. But we think some of these spots are lower because the house is no longer acting as a barrier.”

There had also been a dune in front of the Icehouse condominiums in 2018, Borelli said, and there were other accumulations of sand that existed then but no longer do. “All these locations below people’s decks, all these tiny little pathways — they could be the reason we didn’t have flooding in these locations in 2018 but we did this time.”

Water did not flow across only one property during the Howland Street flood. At the least, 509 Commercial St., 505 Commercial St., and the Icehouse at 501 Commercial St. all had water flowing across them.

Fortifying all those pathways could be a much bigger job than the Gosnold dune, Borelli said. As more houses are raised in the future, the elevation of the land around them could become more important.

“Like it or not, this is going to be a big deal,” Borelli said. “It’s complicated and it’s tricky, but this is the future Provincetown has to deal with.”