The obituary of Clara Schumann, who died on May 20, 1896 at age 76, was published on June 1 of that year in The Musical Times and Singing-Class Circular. The world of music was “poorer for the loss,” it reported.

Born Clara Josephine Wieck, she was a concert pianist held in the highest regard — an 1884 article in The Musical Times called her the “Queen of pianists” — for most of her life, beginning with a hometown performance in Leipzig at age nine. She made her first European tour at only 11.

Clara Schumann performed with Felix Mendelssohn and Franz Liszt; Liszt said he was “enchanted with her talent.” Frederic Chopin said that she was “the only woman in Germany who can play my music.” She was a brilliant interpreter of the works of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms. In an 1893 article about her in the Sewanee Review, T.L. Krebs wrote, “no more poetic and inspired performer ever lived.”

Schumann wasn’t only an illustrious pianist. She was a composer, too. But her compositions were overshadowed by those of her husband, Robert — whom she met at 13 and married at 18 and whose music she championed — and were largely forgotten or ignored until the 1970s and ’80s.

On Sunday, May 4 at the Provincetown United Methodist Church, Red Door Chamber Music will present a concert titled “Musical Mavericks: Bucking the Status Quo.” On the program, among works by Debussy, Dvorak, and Shostakovich, are Schumann’s Three Romances for Violin and Piano, Op. 22.

Part of the mission of Red Door Chamber Music, says co-founder Craig Combs, is “to perform music by composers who have been ignored for reasons of prejudice.” Schumann wasn’t ignored as a performer. But for all her luminous concertizing and despite the admiration of the musical world, she was still a woman.

In her obituary, The Musical Times calls her “artist and woman.” Her achievements as a composer — including cadenzas, sonatas, songs, caprices and polonaises, chamber music, and two piano concertos, one composed when she was only 14 — were mentioned only in a single bland sentence in her obituary published in The Guardian and in a single clause in The Musical Times.

Schumann’s three romances are “masterful,” says Combs. She wrote them in 1853 — the same year she met Johannes Brahms — to play with the virtuoso violinist Joseph Joachim, a longtime friend. “The first time that I listened to the very first one,” says Combs, who has a doctorate in piano performance and literature from the Eastman School of Music, “the opening eight measures struck me as a moment of genius.”

Combs was listening for the influence of Robert Schumann, whose music Combs knows intimately. But the first phrase of the first romance, Andante molto, is a luxuriant chromatic gesture by the piano that Combs says “will melt your heart” and is uniquely Clara’s.

The Andante molto in its entirety is utterly romantic: the violin sings like a wounded soprano, evades the root chord in a sensuous, graceful dance, and swoops sweetly through the artful architecture of the piano part — a no less evocative partner in conversation.

The second romance, Allegretto: Mit zartem Vortrage, meaning “with tender expression,” is lighter, more playful, but with a dark center, as if the violin and piano were two friends engaged in banter, skirting a serious argument. The final note, played pizzicato on the violin, is a rather flippant Picardi cadence.

If the two preceding romances are like conversations, the third, Leidenschaftlich schnell, meaning “passionately quick,” is comparatively wordless. The violin soars in a limber melody over the arpeggiated rippling of the piano. The whole thing seems to take place in the air, weightless and wind-tossed, until the final grounded chord.

Today, with the principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion under attack, it’s difficult not to fear that we are slipping back to a time when art was buried by rules.

In 1839, when Schumann was 20, she wrote in her diary, “A woman must not desire to compose — not one has been able to do it, and why should I expect to?” But she did do it. If she’d been encouraged in life to pursue composition, might she have become a household name like her husband?

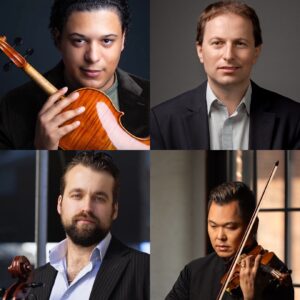

The other “mavericks” represented in Sunday’s concert are well known — Debussy, Shostakovich, and Dvorak — selected by Combs for their harmonic, political, and experimental ingenuity and courage. On the program are Debussy’s Piano Trio in G Major, Shostakovich’s Cello Sonata in D minor, and Dvorak’s Bagatelles. The musicians are violinists Thomas Cooper and Loren Lee, cellist Tyler Michael James, and pianist Constantine Finehouse.

Schumann maintained a long and very close friendship with Brahms. After her husband, plagued by severe mental illness, died in 1856, Schumann and Brahms became even closer.

Schumann’s grandson, Ferdinand, wrote about her and Brahms in a piece published in The Musical Quarterly in 1916. In her final years, Schumann, who he calls “grandmother,” still attended salons and concerts, played the piano, and expressed strong musical opinions.

On Nov. 10, 1894, Brahms presented to Schumann a newly composed clarinet sonata. He was 60 at the time, and Ferdinand reports that he said, “One composes only until one’s fiftieth year. Then the creative power begins to diminish.” Nonetheless, “Brahms was at the piano,” writes Ferdinand, “grandmother at his right turning over the leaves. At the end of each movement, she expressed her delight; Brahms would then ask: ‘Shall we go on?’ and, observing her pleased nod, continued to play.”

Brahms died at 63 in May 1897, less than a year after Schumann. Two years before, in the fall of 1895, Ferdinand writes that Brahms told Schumann “he no longer composed for the public but only for himself.”

Perhaps Schumann thought that was all she’d ever done.

A Woman Composer’s Desire

The event: “Musical Mavericks: Bucking the Status Quo”

The time: Sunday, May 4, 3 p.m.

The place: Provincetown United Methodist Church, 20 Shank Painter Road

The cost: Suggested donation $20; age 17 and under free