My mother was from Las Vegas. On one summer visit when I was 12, she took me to Ceasars Palace to see Cher in concert. During the encore, Cher ran out into the audience and touched me on my head. Boom! Instantly gay. Also, a lifelong Cher superfan.

I will admit that after listening to “Half-Breed” and “Gypsies, Tramps and Thieves” for my entire life, I started her new memoir still under the impression that those songs were at least semi-autobiographical. It’s true that someone on her mother’s side was fractionally Native American, but those highly filtered genes barely reached Cher, and Indigenous culture appears to have played no part in her life.

Same goes for all the “gypsy” stuff. The reality is that Cher was not born in the wagon of a traveling show. She was born in 1946 in the Southern California border town of El Centro. Mama never danced for the money they’d throw, and Papa never sold any bottles of Doctor Good.

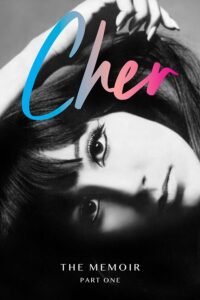

But as I learned reading Cher: The Memoir, Part One (Dey Street Books, 2024), a candid, straightforward personal history that ends a few years after her 1975 divorce from Sonny Bono, her early life was completely different and far more difficult and dramatic than I imagined.

The narrative throughline is the willingness of men to exploit the women in her family — a pattern going back several generations. Jackie Jean Crouch, who frequently changes her name but is best remembered as Georgia Holt, Cher’s mother, lives through some rough early years. Talented, pretty, and possessed of a singing voice like that of a grown woman, little Jackie becomes the family breadwinner thanks to a father eager to exploit his daughter’s talent.

Georgia struggles for decades to succeed in show business. Beauty pageants, stage musicals, and small roles in film and television keep her in the show business grind, but a career-defining break eludes her.

“Mom could get painfully thin because sometimes she couldn’t afford to buy lunch at work with the other actors,” Cher writes. “At five-feet-seven inches, she couldn’t have weighed more than a hundred and ten pounds soaking wet. She also made herself sick with worry and appeared to be in a constant state of stress. I couldn’t help but pick up on the tension and feel it too.”

Georgia marries and divorces a half dozen men. For a time, these alliances, some springing from love and some from necessity, provide security — but none ever provides stability. Like clockwork, the guys end up in some sort of trouble, mostly because of drugs, alcohol, a gambling addiction, or combinations thereof.

Cher’s father, John Paul “Johnnie” Sarkisian, a child of Armenian immigrants, is an undependable small-time hustler and thief who makes a brief appearance when Cher is about 12. There are some good times at first, as Johnnie steps up to take care of his family, but he soon relapses into drugs and crime and exits her life forever. “I knew it was best to forget about the man with my smile who was half the reason I existed,” says Cher. “He was a lot of things, but mostly, he was trouble.”

Between her mother’s never-for-long husbands, who sometimes tried to be part-time father figures to Cher, she bounces from one home to another, including many temporary stays with relatives, friends, in-laws, and grim nuns. The pages practically turn themselves as Cher describes an endless parade of eccentric, awful, and sometimes famous people she encounters. Warren Beatty offers her cigarettes and his girlfriend Natalie Wood’s bikini if she’ll go swimming with him; 15-year-old Cher declines.

In 1962, Cher is a teenager couch-surfing with friends in Los Angeles to avoid her mother’s latest boyfriend when she meets Salvatore Phillip “Sonny” Bono, a man without an addiction — other than to wearing crazy outfits. She ends up sharing a room with twin beds with the 27-year-old Sonny, who believes Cher to be several years older than she is. He discovers her real age only after Georgia storms the apartment to uncover the true circumstances of her rebellious, truth-dodging daughter’s living arrangements.

Sonny’s job as an assistant to Phil Spector, already a hugely successful and influential music producer, introduces Cher to a world where one day she’s sitting quietly in the corner of the recording studio trying not to be noticed and the next she’s singing backup on the most successful record of the era, “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling” by the Righteous Brothers, which Broadcast Music Inc. ranked in 1999 as the most played song on American radio in the 20th century.

Naturally, because almost all the men in this story are untrustworthy, Spector refuses to pay Cher. He hands over a check for $25 after Georgia demands that Sonny get it for her. It’s a foreshadowing moment. Cher will eventually and mistakenly come to trust Sonny to protect her financially — a trust that, as surely as the sun will rise, he will betray.

An initial but explosive global success for the not-quite-legally married duo Sonny and Cher fades almost as fast as their meteoric rise. Not as thrown by whiplash reversals of fortune as Sonny but wary of repeating her mother’s chronic instability, Cher allows Sonny to put them on a grueling path of endless small gigs and roadwork to reclaim their fame. They slowly reinvent themselves as a wisecracking husband and wife cabaret act that eventually leads to massive success on television with The Sonny & Cher Show, starting in 1971.

During this period, Sonny’s controlling character comes to the fore. Cher is forbidden from listening to music, going to movies, talking to the men in the band, or having any close friends. He keeps her so busy with touring in between filming their show that she has almost no contact with the world outside the one he has shaped for them.

Of course, the scope of Sonny’s betrayals eventually come to light. Cher finds the strength to file for divorce. Notably, Lucille Ball, a friend of Georgia’s, is the one who encourages Cher to leave, telling her, “F him. You’re the talent.” Later, Tina Turner comes to Cher for advice on leaving Ike. Good men are exceedingly elusive in Cher’s world. Later, other famous men like Gregg Allman and Gene Simmons will also let her down. The few who actually help her, like Bob Mackie and David Geffen, are gay.

The book ends with Cher setting out to make a name for herself as an actress. Part Two of the story, promised next year, will cover that era. But Cher’s busiest and most successful movie-making period leading to her Oscar for Moonstruck ends in 1988. The 36 years that follow movie-stardom are filled with her remarkable solo recording and touring era, so fingers crossed there will be a Part Three.