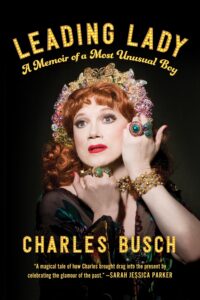

Charles Busch — the renowned “male actress” of stage and film, playwright of dozens of shows including Vampire Lesbians of Sodom, which ran for five years off-Broadway, and the Broadway smash The Tale of the Allergist’s Wife — has finally written Leading Lady: A Memoir of a Most Unusual Boy.

“I lived my life as a narrative as it happened,” he writes at the start. Tragedy strikes early with the sudden death of his mother. Warned by her doctors that having children would strain her frail heart, she goes ahead and has three, two girls and a boy. Then, when Busch is just seven, he is told by a group of passing older boys, “Somebody’s mom dropped dead on the LaRosas’ lawn.” He quickly discovers it was his mother.

“I was both a spectator and a participant in this drama, which I suppose set the pattern for the rest of my life,” he writes. His mother’s death raised a question that Busch would ask himself again and again, at each success or hardship: “What happens to me now?”

It soon becomes clear to his mother’s sisters that the children’s free-spirited father is not capable of raising children — he’s a hapless sort whose head is always in the clouds even while six tiny feet are waiting for him on the ground. He frequently leaves Charles and his sisters on their own while he is out dating the widows in his grief counseling group, raids his children’s college fund to pay for a trip to Europe with one of his ladies, and eventually marries again and moves out to live with his new wife and her children with one day’s notice to his own juvenile children.

An absent father, in the end, becomes a blessing in disguise. Busch moves in with his loving and practical aunt, who has a Park Avenue apartment as well as infinite patience and understanding for her unusual boy.

On a trip to a fabric store, for example, a shiny piece of cloth catches Busch’s eye. His aunt asks a salesgirl to cut off a sample and then hands it to him. A shiny piece of fabric, he tells us, could keep him occupied for hours. She helps him finagle his way into the theater department at Northwestern despite poor grades and a terrible audition. She has that kind of Auntie Mame magic, or so Busch wants us to believe. Spinning stories of stalwart, clever, savvy women is his stock in trade. He can’t help but view the pass through a Vaseline lens and some line-smoothing amber gels.

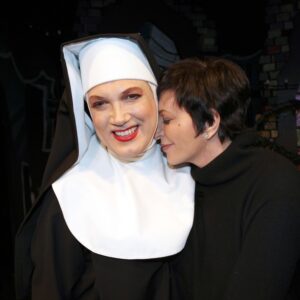

At Northwestern, Busch can’t be bothered to play any of the parts offered to him in the drama department. Male roles don’t interest him. It’s only when he enlists his roommate to perform with him in drag as part of a conjoined twins act — a surprise hit on campus — that he realizes he is meant to play leading ladies rather than gentlemen.

“Playing a female role gave me a freedom of movement and vocal variety I had never known,” writes Busch. “Drag for me was not an expression of outrage or even satire, but rather a passageway to channel the feminine in my nature, which turned out to be a place of authority.”

The trappings of celebrity, fame, and acclaim don’t seem to alter Busch. Even an early stint as a male prostitute doesn’t seem to leave a mark. He remains the same determined, appreciative little boy who delighted in a fabric scrap. Late in the book, he writes about a chance encounter with the theater critic whose review he believes launched his first great success. Busch gushes his gratitude; the man seems not to remember the play all that well. But it’s a telling moment about Busch’s nature.

He’s not blindly appreciative, though: Busch is candid about his discontent with being called a drag queen. He was never part of the New York club circuit that gave birth to the modern drag movement. He never wore drag outside the theater. He saw himself strictly as a playwright and a male actor who played female roles. The parts he created for himself were frequently melodramatic women-in-danger roles tied to the Golden Age studio style of female acting. He loves a lady, especially if that lady is well dressed and exceptionally detailed in her mannerisms, with a cache of witty asides at the ready.

Today, however, he’s lightened up a little bit, happy to be included in the endlessly growing umbrella of drag performance. And it’s not over. Although he implies that he’s ready to settle into the Dame Charles Busch era of theater royalty, he’s still more than capable of knocking out some more hits.

He just has to keep asking and answering that question: “What happens to me now?”