Outer Cape Calendar

Art of Social Distancing

Artists Megan Hinton and Paula Erickson found a rusty metal office desk at the Wellfleet Dept. of Public Works yard off Pole Dike Road. Hinton was inspired to create a site-specific installation, Remote Office, with Erickson performing at the desk. Hinton decorated it with objects painted a rusty orange patina and calls the piece a “response to the Covid-19 pandemic” and “an intervention on the landscape.” See her photograph documenting the project on this page — that’s Erickson in shadow under her umbrella.

Brunch With Mackenzie

Throughout Pride Month, Pilgrim House and Live From Provincetown are presenting “Sunday Service Digital Drag Brunch” online every Sunday in June at 1 p.m. with Mackenzie, a drag queen so vivid, she’s beyond virtual. You can watch live (the food is up to you) on the Pilgrim House Facebook page.

Bourne Again

Among the virtual events offered by the Eastham Public Library, we recommend the exhibit by the Painted Ladies of Bourne, on view online at easthamlibrary.com throughout June. Also on the library’s site, from June 20 through June 26, you’ll find a prerecorded family-friendly concert combining jokes and music with Dave Maloof on piano and ukulele.

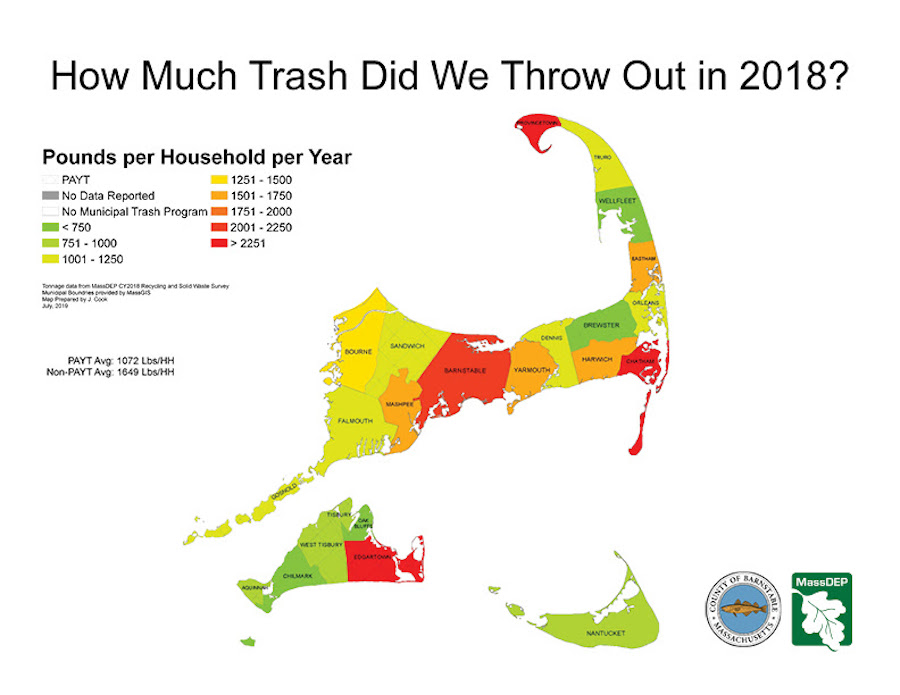

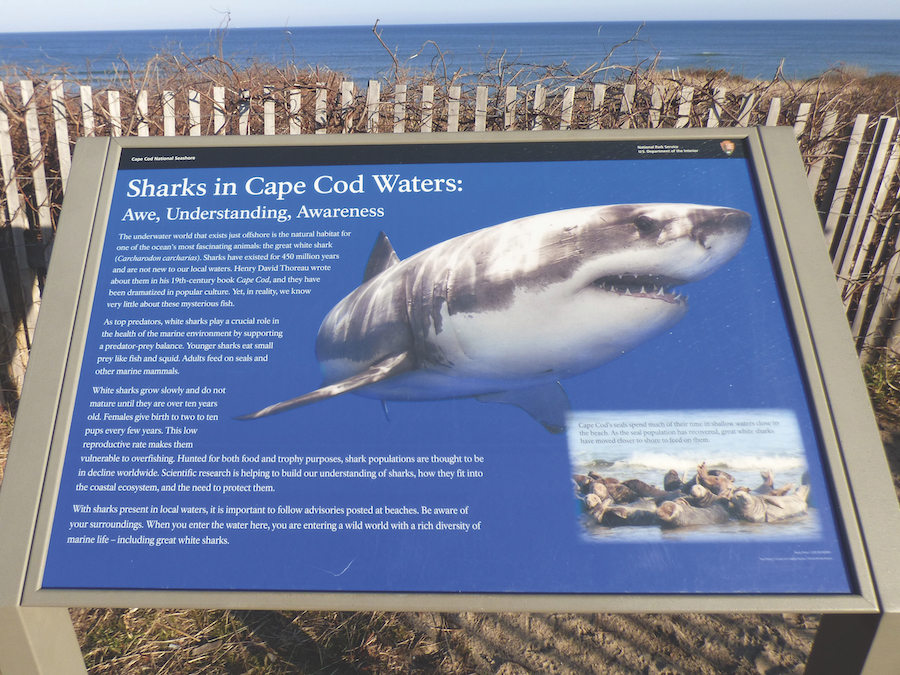

Coastal Clean Up

Willie’s Superbrew, working with the Center for Coastal Studies, is coordinating and sponsoring a cleanup of all Cape Cod beaches on Saturday, June 13, and Sunday, June 14. Sign up at superbrew.com/beach-cleanup-signup and claim a space at your favorite Cape beach. To allow for social distancing, only one party per day is allowed on each beach.

Outdoor Yoga

Mussel Beach Health Club in Provincetown has started outdoor yoga and spin classes, conforming with social distancing guidelines, at the Crown & Anchor pool deck. A summer membership costs $299. To join, go to musselbeach.net.

Feast Your Eyes

Provincetown Public Library is hosting a free cooking class, “Feasting From Your Local Farm,” via Zoom with Chef Liz Barbour of the Creative Feast. The free class will take place on July 15 at 3 p.m. (reserve your space now) and will focus on cooking with local ingredients. Visit the library’s Facebook page and click on “events.”

Acts of Love

Wellfleet Preservation Hall is doing another virtual Feed Your Love Open Mic on Zoom on Wednesday, June 17, at 7 p.m. Email John Beardsley at [email protected] in advance to either attend or perform. For details, go to wellfleetpreservationhall.org or to the hall’s Facebook page and click on “events.”

Day for Night

Addison Art Gallery is presenting a virtual reception for the paintings and sculptures of artist Jennifer Day. Proceeds from all sales will benefit Wellfleet Harbor Actors Theater. Go to the gallery’s Facebook page on Saturday, June 13, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Outermost Stretch

Outermost Yoga in Provincetown offers a slew of live-stream classes for all levels. They are free but donation-based, so you are encouraged to support your instructor via his or her Venmo handle, which you can find on the class description at outermostyoga.com/virtual.

Painting With Hocking

Outer Cape painter Pete Hocking is teaching the online workshop “Three Ways Forward: Weather, Pathways, and Space” through the Provincetown Art Association and Museum. There are three sessions: Saturday, June 13, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.; a one-on-one consult with Hocking on Sunday, June 14; and Saturday, June 20, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. The workshop costs $250 ($240 for members). To sign up in advance, go to paam.org and click on “Events.”