The viewer is immediately drawn to the eyes. This is true of many paintings by Provincetown art colony founder Charles Webster Hawthorne. They are dark brown and serious. The glint on the wire-rimmed glasses matches that of the steely cello strings.

Though the cello player’s right hand is out of view, his left is ready to play. All four fingers are pressed down on the strings. On the body of the cello below, the instrument is noticeably worn in the place where the player’s hand would rest, as if on a friend’s shoulder, when not playing.

At the bottom right is the artist’s signature. Hawthorne did not often sign his paintings. But in this case, it is large, unmistakable.

The painting in question is a portrait of Leo Tushnett by Hawthorne. Tushnett was principal cellist of the Radio City Music Hall Symphony Orchestra in New York. When he was visiting Provincetown sometime in the early 1900s, he gave Hawthorne cello lessons, Tushnett’s granddaughter Carey Harben tells the Independent.

In exchange for the lessons, Hawthorne painted this portrait. It is still owned and cherished by the family.

This is just one example of a part of Provincetown history that is nearly forgotten. Though best known as an art colony, Provincetown also has a rich musical past. Some artists, such as Hawthorne, did double duty. They were both painters and musicians.

“Music was one of his great loves,” writes Hawthorne’s son, Joseph, of his father in his introduction to the book Hawthorne on Painting. “This can be seen from the number of parallels he draws from music in his criticism. In New York, he was a great concertgoer, and, as far back as I can remember, there was chamber music in the house. He started as a cornetist in the Richmond town band and took up the cello later on.”

Joseph went on to be a well-known conductor and founder of the Provincetown Symphony Orchestra, which flourished from 1955 to 1967. Performing at Provincetown Town Hall, the orchestra recruited professional musicians from all over the country who summered on the Cape.

“Beauty in art is the delicious notes of color, one against the other,” Charles Hawthorne writes in Hawthorne on Painting. “It is just as fine as music and it is just the same thing, one tone in relation to another tone.”

Though Hawthorne drew on music in his teachings, he rarely painted musical subjects. The portrait of Leo Tushnett is unusual in that way.

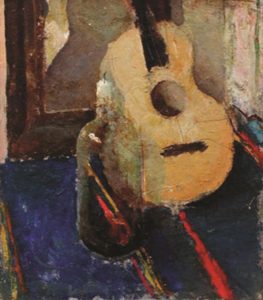

Hawthorne’s student Edwin Dickinson, however, was a different story. His Still Life With Guitar, part of the Provincetown Art Association and Museum’s permanent collection — and currently on view in an exhibit there — is just one of many examples of his paintings with musical subjects.

Another is The Cello Player, painted by Dickinson between 1924 and 1926, and now in the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. It makes for a telling comparison with Hawthorne’s portrait of Leo Tushnett. Though the mood is entirely different, one can see Hawthorne’s influence on Dickinson in his treatment of light, including how it reflects off the cello strings.

The art historian John Driscoll proposes that Dickinson’s highly symbolic painting concerns his brother Burgess, a composer, who committed suicide. In addition to a cello, it depicts two pianos, and sheet music to a Beethoven string quartet and Mozart’s opera The Marriage of Figaro.

Dickinson was also a musician in his own right. Janice Biala’s untitled painting of a violin, in the collection of the town of Provincetown, is an homage to Dickinson. A photograph of Dickinson taken in his Wellfleet studio shows a violin hanging from the wall.

A painting by Elaine de Kooning depicts Dickinson playing the violin and the artist Daniel Brustlein playing the cello. Provincetown painter Salvatore Del Deo, however, tells the Independent that Dickinson was an amateur cellist. It’s possible that he played a few instruments.

For both Hawthorne and Dickinson, music appears to have been an inspiration and refuge.

“A great composer could find inspiration for a symphony in a subject as simple as the tinkle of water in a dish pan,” Hawthorne writes in Hawthorne on Painting. “So, can we find beauty in ordinary places and subjects. The untrained eye does not see beauty in all things — it’s our profession to train ourselves to see it and transmit it to the less fortunate.”