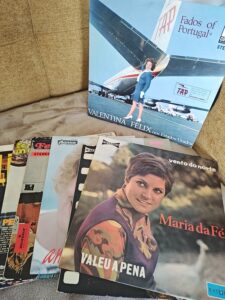

At her home in South Dartmouth, Celia Maria recalls the fado singers who have inspired her. She opens the doors to her media center to reveal hundreds of LPs, 45s, and CDs.

“There were so many,” she says. “Fernanda Maria; two gentlemen, Manuel de Almeida and Fernando Farinha. Those are the big names in Portugal.”

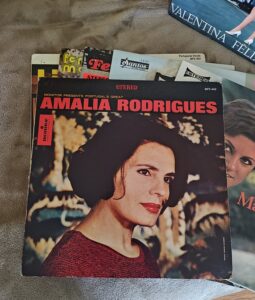

Singer Amália Rodrigues, who died in 1999, “was the queen,” Maria says, and her personal favorite. On a 1965 record cover, Rodrigues gazes steadily into the distance.

Maria, who will turn 78 in July, is a fadista — a singer of fado, a form of traditional Portuguese folk music. On Saturday, June 28, she’ll perform at Provincetown Town Hall in the Portuguese Festival’s time-honored fado concert, accompanied by Viriato Ferreira on the viola baixo and Loic da Silva on the Portuguese guitar. This will be her 23rd year performing at the festival.

Maria was born in Porto, Portugal into a family of nine children. When she was four, she was sent to stay with her grandmother in Angola, at the time a Portuguese colony, where she lived for six years. It was there she began to sing fado at her grandmother’s request.

“I used to lie down in bed with her and sing,” Maria says. As a young child, she listened to fado on the radio. When she got older, she bought fado records and attended performances. Though she never received any formal music training, Maria had a good ear and natural aptitude that developed into true talent through practice.

When she was 21, Maria came to New Bedford to live with her older sister, Margarida. Maria worked in restaurants as a server — after her shifts, she’d sing at the same restaurants. Eventually, she stopped serving and just sang. Her career as a fadista has taken her across the U.S. and to Portugal, Bermuda, and Canada.

In 2011, fado was formally recognized as a world music tradition when it was added to the representative list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. But opportunities to perform in the U.S. have dwindled in recent years, Maria says. She remembers singing at restaurants in New Bedford, Fall River, and Cambridge; now, she says, those places either don’t exist or no longer offer fado. That’s why the Saturday evening fado concert at the Portuguese Festival is so important to her: it’s a rare opportunity to perform her art for an audience.

Maria says she sings Lisbon fado, a folk tradition, as opposed to Coimbra fado, which is considered more academic and is performed solely by men. Those are the two main varieties of the genre, but there are many styles within them, Maria says, which take their names from particular guitarists, singers, or locations. She describes fado alberto (which allows for improvisation), fado mouraria (which is melancholic), and fado corrido (which has a fast tempo and can be cheerful).

In any fado performance, two guitar players typically accompany a single vocalist. The guitarrista (on Saturday, Loic da Silva) plays the Portuguese guitar, which has a broad soundboard, a short neck, and 12 strings. The instrument has a bright, expressive timbre and is famously difficult to master. Usually, guitarristas are men, but more women are learning, Maria says. The violista, the other guitar player (Viriato Ferreira on Saturday), plays the viola baixo, which looks like a classical guitar but is an acoustic bass guitar with four strings.

Sometimes a singer might perform with just one instrumentalist. “If you don’t have a viola, you can just sing with the guitar,” Maria says. “If you don’t have a guitar, you can just sing with a viola. But it’s not the same. The viola and guitar have to be married.”

What unites all fado styles is saudade. Maria offers a succinct definition: “It means missing.”

But Saudade has no exact equivalent in English. Though it’s often associated with homesickness and described as melancholia or profound longing, saudade defies categorization. There is pleasure in it. “Fado is so beautiful,” Maria says. “If it’s a sad song, sometimes there are tears. But tears or no tears, we feel happy at the same time.”

One of Maria’s favorite fados that she plans to perform Saturday is “Carmencita,” written by Frederico De Brito and Pedro Rodrigues and famously sung by Amália Rodrigues. “It’s about love,” Maria says. The song follows a young woman who abandons her family and her past to pursue a sonho lindo, a beautiful dream, which is never realized. The song’s second stanza:

The caresses and affection

She lost along the way

without ever having known them

And she kept seeking adventure

As if she were in search

Of a lost grain of sand.

Maria first heard “Carmencita” on the radio as a teenager. Now, her own rendition reflects her experiences — moving away from her family, the tragedy and beauty of everyday life.

“People say I put a lot of love into this song,” Maria says. “You have to sing with love.”

The word “fado” means fate, or destiny, but it’s often about real life. The audience doesn’t have to understand Portuguese to understand fado — the fadista imbues the performance with personal knowledge of grief and joy. Singer and instrumentalists seem to communicate in a realm beyond language.

In performance, the fadista walks onto the stage and tells the guitar players her chosen fado. Then, Maria says, “We close our eyes, and the words just come out.”

From the Heart

The event: Celia Maria sings fado at the Provincetown Portuguese Festival

The time: Saturday, June 28, 7 to 9 p.m.

The place: Provincetown Town Hall, 260 Commercial St.

The cost: Free