Carol Fitzsimons’s richly colored and textured works are painstakingly created by adhering small strips of string to canvas board with a toothpick and Elmer’s glue. “It’s like painting with fiber,” she says.

Her dining room table in Wellfleet is covered with boxes of the yarn and thread she uses to create images of landscapes and animals. It’s a fitting environment for her craft-inflected art making, if not an ideal one. (She fantasizes about parking an Airstream trailer in her yard to use as a studio.)

The interior of Fitzsimons’s house reflects the same fascination with surfaces and materials evident in her artwork. Her shelves are full of objects. One displays a collection of color wheels; another is bird-themed, with guidebooks about birds and a birdhouse decorated in abstract patterns. The longer one stays in her house, the more there is to see. There are mobiles, a felted rabbit, a papier-mâché bust of a walrus, fish-shaped lamps, and an oak-rimmed couch with carvings of ducks and fabric inspired by glass artist Dale Chihuly. Fitzsimons commissioned pillows from a seamstress in India to match the couch and created a tapestry for the coffee table to echo the couch and pillows.

Collecting was Fitzsimons’s entry into her current art practice. After studying history and philosophy of religion at Wells College in upstate New York, she took a brief stab at a job in the arts.

“I thought I wanted to illustrate children’s books, and I thought an easy entry into that was making greeting cards,” she says. “Eventually my father, who worked in insurance, told me to get a real job.”

Fitzsimons built a career in her father’s profession. “You always hear stories about people who stay in white collar jobs, and that’s what I did,” she says. “It was incredibly boring and as the years went on, it was incredibly stressful.”

During her insurance career, she spent two weeks every summer at her parents’ Wellfleet house with her husband, Kevin Fitzsimons. When she found herself unable to collect the expensive artwork she encountered while on vacation, she began to recreate paintings in fiber, developing a process that began with a drawing on newsprint that was transferred to a canvas board. Fitzsimons then blocked in color with markers and filled in the design with thread, string, and yarn. It was a painstaking and time-consuming process: “One picture would take 10 years because I would only do it two weeks out of every year,” she says.

Her pace picked up in 2014, a year after she took an early retirement and moved from Bergen County, N.J. to her family’s home overlooking Chipman’s Cove in Wellfleet. Encouraged by a growing interest in her paintings, she began developing her own imagery.

At first, she was guided by practical concerns: “I started thinking about popular things to sell here and began to make pictures of seabirds like herons, egrets, and seagulls,” she says. When I visited her, Fitzsimons was working on a painting of a macaw parrot. Part of the canvas board was colored in with markers, and Fitzsimons moved back and forth between the leaves and the bird’s feathers, using three different greens for the foliage. Light and dark blue threads formed the intricate wings. Each thread was carefully measured and cut to fit the drawing.

Although she now works with her own imagery, Fitzsimons is still infatuated with the art of others. “It amazes me how apparent influences are once you become familiar with more artists,” she says. She was captivated with the paintings of David Hockney after attending a film about him at Cape Cinema. “I was blown out of the water,” she says.

Inspired by his large-scale paintings of rural landscapes, she started creating her own versions and experimented with different colors and yarns. “Hockney’s work is like a coloring book,” she says. “And I’m really good at coloring and staying inside the lines.” Her work echoes Hockney’s in its pure colors, flat spaces, and range of textures. But where Hockney uses different marks to describe textures, Fitzsimons does so through different yarns — some iridescent and thin, others woolly and bulbous.

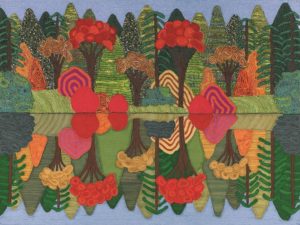

Fitzsimons says she was also influenced by Adrian Berg, an older artist friend of Hockney’s who died in 2011. “Can’t you see how his work was a jumping-off point for Hockney?” she asks. The two British artists shared an affinity for cultivated landscapes, which they painted with a playful fearlessness. Inspired by Berg’s paintings of Regent’s Park in London, Fitzsimons recently completed three pictures of trees and their reflections in water.

Fitzsimons’s reflection paintings are among her most sophisticated. In Autumn Reflection, she works with a simple, almost severe composition: a line of trees and shrubs at the water’s edge. The image is split in half, the bottom mirroring the top. Different threads subtly articulate the difference between the foliage and its reflection on the surface of water.

“The idea was the top half was varying textures of low luster fibers,” says Fitzsimons. “The bottom half is all embroidery thread, which is lustrous without texture.” This contrast is most evident in the green triangular trees, which are created with a thick yarn that suggests the soft matte texture of evergreens; their reflections, described with embroidery thread, are delicate and airy. She continues this mode of working in another painting of Uncle Tim’s Bridge in Wellfleet but pushes the value contrast of the threads to create an even greater distinction between the foliage and its reflection.

As much as Fitzsimons’s work is a kind of painting, it also relates to domestic crafts like sewing and embroidery. In merging the two traditions, she blurs the distinction between craft and fine art and is just as comfortable identifying her grandmother as an influence on her work as she is Hockney and Berg.

“My grandmother was an incredible embroiderer,” she says. “I used her ideas as a jumping off point. I can’t sew, but I can glue.”