Drawing is a personal art. There’s often not much more than a line of ink or graphite dividing an artist’s idea from the artwork. It is both direct and exploratory.

In Carmen Cicero’s current show of drawings and watercolors at the Cape Cod Museum of Art, his works move in many directions. The drawings, mostly ink on paper, are like pieces of a narrative unfolding rapidly from the artist’s mind. The watercolors are slower. In these pieces, some of them five feet long, Cicero builds on the suggestions in his drawings to create colorful, fully realized scenes.

Cicero, who will be 99 this summer, is still making art. He was born in Newark, N.J.; now he splits his time between Truro and New York City, where he lives in a fourth-floor walkup loft. His career as an artist has spanned various movements, from abstract expressionism to figurative expressionism. He’s balanced his art practice with a serious commitment to playing the saxophone. Drawings and watercolors, with their sense of endless possibility, seem a good match for this artist’s energy.

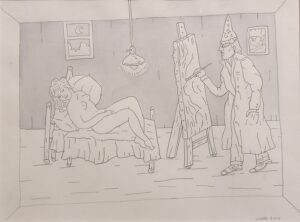

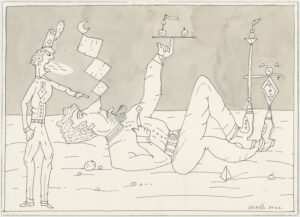

Cicero’s exhibition, curated by art writer David Ebony, is organized on five topics: adventure, art, humor, joie de vivre, and music. Each group has both watercolors and drawings. The section on art includes pictures of a male artist in his studio either alone or with a female model. The artist is a slightly absurd character, wearing what appears to be a wizard’s cap. In many of the works, a light bulb with lines radiating from it, perhaps symbolizing inspiration, hangs above the artist’s head. The inspired artist isn’t a romantic figure in Cicero’s pictures. He’s funny, even a little pathetic, and seems to be lifted from the world of comics.

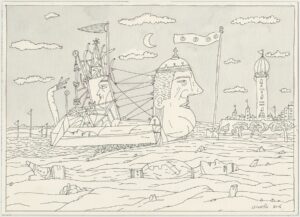

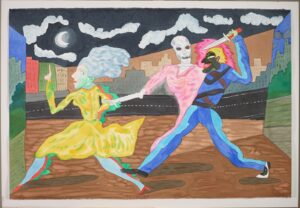

The rear of the gallery is devoted to adventure and includes large watercolors and intricate pen-and-ink drawings of fantastical ships. One watercolor, Rage, is an urban scene of a man with a raised knife chasing a woman. Another, The Story of Life, is an erotic scene with reclining women, devilish men, and a snake. Danger is present in many of Cicero’s pictures, especially in his depictions of the relationship between men and women.

The exhibition was produced in conjunction with a handsome book of Cicero’s drawings and watercolors published by Abbeville Press in 2024. Its subtitle, “Tales of Intrigue, Danger, and Humor,” is also the name of an essay Ebony, a contributing editor at Art in America, wrote for the book. The exhibition and book propose different ways of grouping Cicero’s sprawling output, but a viewer can find many alternate pathways through the work. What’s clear is that there’s no singular or linear route. It’s more a series of intersecting, circular paths spanning 70 years (the oldest work in the show is from 1954, and the most recent is from last year).

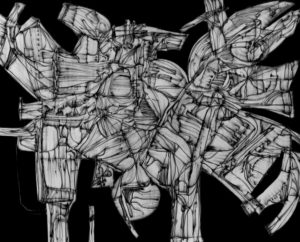

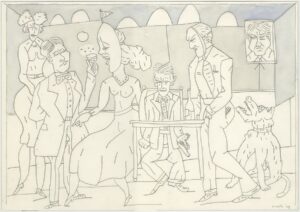

An ink drawing from 1954, Small Animal, is representative of Cicero’s early abstract expressionist work, with a black-and-white mix of gestural lines and flat, biomorphic shapes. The Mob, from 2009, looks dramatically different. It belongs to a body of drawings featuring figures, often wearing masks or costumes, rendered in delicate ink lines.

The narratives in these pictures happen in box-like spaces (or stages) defined by architectural lines and faint washes of value. The differences between these two pictures represent an evolution in Cicero’s work, but there’s an improvisational way of building an image that unites them.

In his narrative drawings, the images seem to be invented through chain reactions: one character responding to another. In The Mob, a man with a gun sits at a table while a masked man stands above him, glaring. A woman on the other side of the table points at a well-dressed man looking at her while another figure observes them from a distance.

Cicero’s approach to making pictures, whether abstract or representational, is consistently influenced by the spirit of abstract expressionism with its in-the-moment associative ways of building an image, which itself is rooted in surrealism, an earlier movement. This mode of working is also apparent in his imaginative landscape and architectural drawings like The Poet’s Vision, where elements of a city seem to grow out of each other.

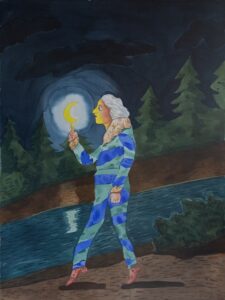

With Cicero, the subconscious naturally rises to the surface. Navigating through the exhibition, one encounters repeated motifs — masks, people pointing, circus performers, artists and musicians, the Moon, lightbulbs. A Freudian psychoanalyst would have fun decoding these symbols. Like dreams, their precise meaning might be elusive to the layperson, but it’s clear this is a personal language related to Cicero’s fears, fantasies, fixations, and observations both of himself and our culture.

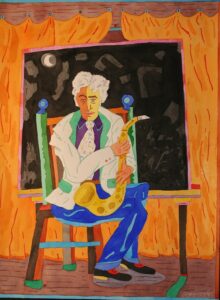

My Life in E Flat, a self-portrait, is the most personal image in this exhibition. The watercolor has elements that reverberate in the other work: exuberant color, a stage-like space, a musician, and a painting on an easel. The painting shows the artist seated, perhaps backstage, with a saxophone in his hand. He looks down, caught in a moment of reflection in the midst of the loud color. It’s a place of stillness in an exhibition with much movement.

Behind the images, of course, is the artist himself, as My Life in E Flat reminds the viewer. Despite the fiction and invention in this exhibition, ultimately, these are personal, self-probing works made over a long, adventurous career.

Intrigue, Absurdity, and Danger

The event: Carmen Cicero’s drawings and watercolors

The time: Through Oct. 5; opening reception and gallery talk, Thursday, July 17 4 to 6:30 p.m.

The place: Cape Cod Museum of Art, 60 Hope Lane, Dennis

The cost: General admission: $15