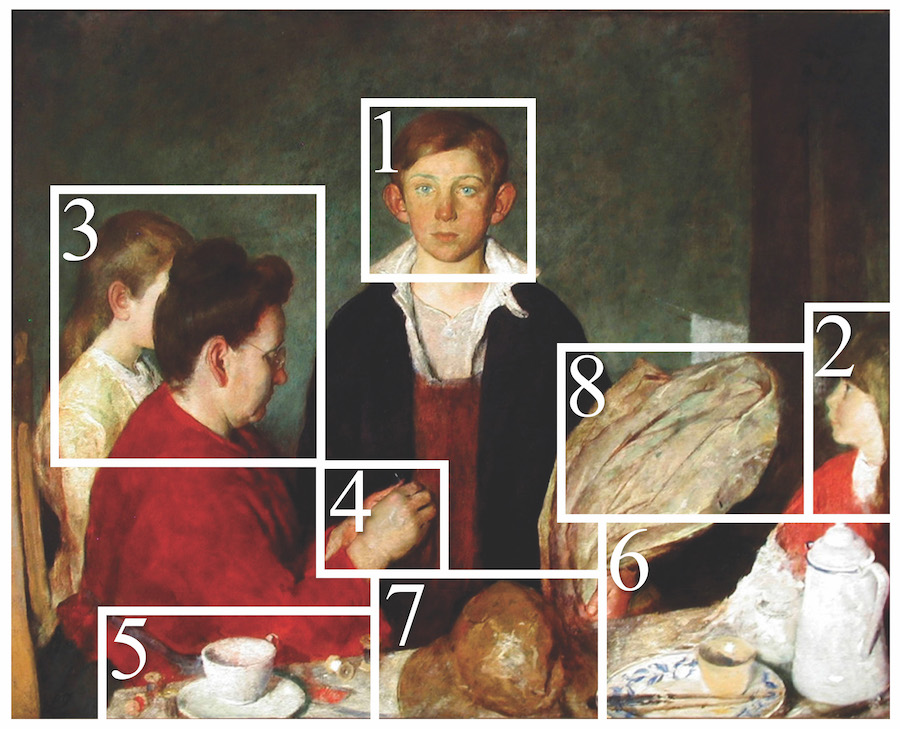

At four by five feet, His First Voyage, by Charles Webster Hawthorne, is an imposing painting. Its figures are roughly life-size. The subject is, seemingly, just a domestic scene. A boy is surrounded by his sisters and mother, the table laid with the makings of afternoon tea. The title, however, reveals something weightier: the boy is about to embark on his first sea voyage, which could potentially be perilous and harrowing.

Hawthorne is famous for founding the Cape Cod School of Art in 1899 in Provincetown. He taught numerous memorable pupils, including Edwin Dickinson, Henry Hensche, and Lucy L’Engle. Many of Hawthorne’s paintings, which take inspiration from the Portuguese fishing community in Provincetown, focus on the internal psychology of the characters.

His First Voyage was painted in 1915, one year after the founding of the Provincetown Art Association (and, later, Museum, or PAAM), which Hawthorne served as honorary vice president. The painting is one of the celebrated masterworks of PAAM’s permanent collection, a gift of Charles’s son, Joseph, in 1949. It is frequently hung in exhibits from the collection but is currently in storage.

- That Face

Looking at the painting, you are instantly drawn to the central figure’s luminous, pale blue eyes. His expression is difficult to parse. Is he sad? Scared? Courageous? Stunned? He appears to be on the brink of adolescence. His complexion is ruddy, and he has a swath of red hair.

His ears stick out in the way that boys’ ears sometimes do, as if he hasn’t yet grown into them. One can see Hawthorne’s influence on Norman Rockwell, briefly his student, in his depictions of gangly adolescents. The boy’s youthful appearance reinforces the undercurrent of the painting: the impending voyage is his coming-of-age.

But who is the model? According to a 1999 article in the Provincetown Advocate, it is 13-year-old Jacob Smith, a local boy who worked in the lumberyard. Neither Portuguese (suggested by his red hair) nor from a fishing family, Jacob is instead acting the part in a story all too familiar for Provincetown.

- Watching Big Brother

The little girl on the right was modeled by Jacob’s youngest sister, Fannie. She was eight years old at the time and recalled modeling for Hawthorne in the Advocate (she died in 2001). Shown in profile, she is the only figure other than Jacob for whom a white glint of eye is visible. She seems to be looking up at her brother in admiration.

- Portuguese Pedigree

The figure on the far left was modeled by Nellie, Jacob’s other sister. Her face is hidden by Clara Smith, Jacob’s mother.

Descendants of the Smith family still live in Provincetown. In fact, Lilli Osowski, who was profiled for her work with veterans in the May 21 issue of the Independent, is Jacob Smith’s great-great-granddaughter. Although the Smith family was not Portuguese, many of its descendants are now Portuguese through marriage.

- A Needle Pulling Thread

The mother in the painting wears spectacles in order to sew a button on the boy’s jacket. The glint of a silver needle is visible in front of the dark fabric. Hawthorne plays with his characters’ gazes — Nellie’s is hidden, Clara’s is focused on sewing, Fannie’s is at her brother, and Jacob’s is directly at Hawthorne … or us.

5 & 6. Nature Morte

The table is covered with spools of thread from the mother’s sewing. They are the colors that make up the painting: black, white, and red.

The tableau also includes a cup and saucer, plate and knife, coffee pot and sugar bowl. Richard Mühlberger, in his book Charles Webster Hawthorne: Paintings & Watercolors, says that these items are “all symbolic of parting.”

- Hats Off

The Fisher Boy, another painting by Charles Webster Hawthorne in the New Britain Museum of Art, shows how an oilskin hat is worn by fishermen. (Photo New Britain Museum of American Art)

Also on the table is a fisherman’s oilskin hat. Compare this hat to the one in The Fisher Boy (on this page), which Hawthorne painted seven years earlier. These hats were made from waterproof oiled canvas — revealed by the way Hawthorne has painted the light on it — and were longer in the back to prevent water from trickling into the fishermen’s coats.

- Danger at Sea

The boy is also holding an oilskin coat. One can tell that the coat is stiff from the way he holds it. He is dressed very warmly: waterproof coat and hat, jacket, apron, shirt, and undershirt. It is blisteringly cold on the high seas.

While Hawthorne’s scene may not be modeled by an actual Portuguese fishing family, it tells a story rooted in truth. According to Mühlberger, by the time Hawthorne arrived in Provincetown in 1898, there were over 1,000 recorded shipwrecks off Cape Cod. The perils associated with fishing lend special significance to the painting, and to the boy’s poignant expression.

These dangers are precisely the reason why the Blessing of the Fleet came to be: to pray for the safe passage of fishermen, young and old, into unknown waters.