For all the beauty of the Outer Cape, for all the luck we feel to live in this gorgeous place, it isn’t all dreamy sunsets and fabulous gatherings. Not all the time, and not for everyone.

Living in a small town, we see those who struggle, whether it’s due to an illness, a loss, or one’s own interior weather. Vulnerable members of our communities are more visible than in a larger city, where faces might be known but not names or stories. In a small town, we all know someone who knows someone; we note an absence or a shift in routine. Sometimes, we ourselves are the ones flailing.

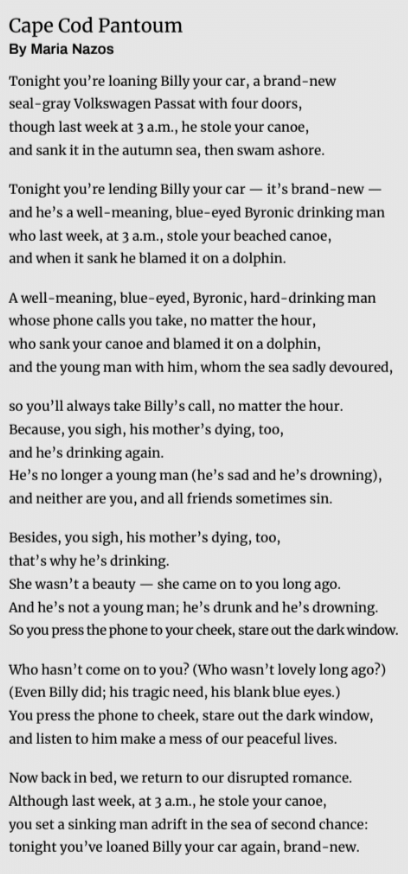

And when someone dear to us is struggling, how do we love them? How does our worry express itself? How does the news spread, and how do we bear witness or try to help? This is the subject of Maria Nazos’s tender, clear-eyed poem “Cape Cod Pantoum.”

I asked Maria about the poem’s origins. “It reflects so much of Billy and what I went through,” she says. “Once I heard someone say, ‘You come to the Cape to heal or to die.’ I agree! This poem represents treading in that liminal, self-destructive space where even the best of us have fought to stay afloat.”

Maria and I worked together for a season or two on the Portuguese Princess Whale Watch 15 years ago. I didn’t know then that she was a poet. She probably didn’t know that I was, either. We shared hours on the water in our separate realms: she on deck and in the galley, me at the microphone as naturalist. It has been a pleasure to find her name years later in prestigious literary circles and to see where she and her poems have traveled. And it’s a pleasure to welcome her back through these pages.

As you read “Cape Cod Pantoum,” you might feel a bit of déjà vu. Words and even whole phrases repeat themselves: blue-eyed Billy the Byronic drinker, the loaned car, the canoe, the dolphin excuse, his dying mother. Images circle and recur, swirling through the poem. That’s because of the form Maria has chosen.

The pantoum is a poetic form from Malaysia that braids repeated lines from stanza to stanza, ending back where it began — albeit changed. It is a perfect form for a poem that takes as its subject the looping difficulties of a troubled, beloved soul.

By repeating scenes and descriptions, we have a sense of the worried circling of a mind in turmoil, the cyclical nature of addiction, and how destructive behavior feeds upon itself. We also see how the speaker of the poem keeps trying, keeps lending the car or canoe or her ear, even if the result might not be good.

Because that’s what you do: you hold on, keep reaching out, keep listening through the dark conversations in hope that something shifts toward the light — because you want to be there for that, too.