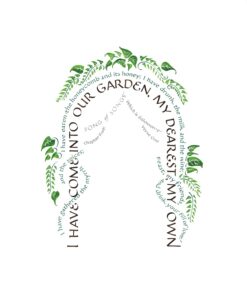

Margaret Shepherd’s calligraphy, now on view at the Wellfleet Public Library through Nov. 3, looks like it was created with ease. The lines of text, which are taken from the Song of Songs — the book of the Old Testament known for its sensuality — flow gracefully across the 45 works, often coalescing into images or geometric designs.

Shepherd’s process is more arduous than it looks. “I have to grind away at it,” she says. “Each one of these probably took at least 25 rough drafts.”

Shepherd works in a studio in Boston and lives part of the year in a cottage on Gull Pond in Wellfleet. She’s pleased that the final result of her labors looks effortless. “I’m like an actor delivering the lines,” she says. “I want the person not to look at me but to listen to the performance.”

This project had been percolating in Shepherd’s mind for a couple of decades. She first lettered a passage from the Song of Songs for a friend’s wedding and thought a larger project would have potential: the book’s poetic account of the relationship between a young woman and her lover, for example, would be great material for works on the theme of romantic love. But she found English translations from the original Hebrew a stumbling block.

A Sunday-school class introduced Shepherd to the text as a teenager, but she says the biblical language kept her “at arm’s length from the human feelings.” Later, as an adult trying to work with the text, she encountered similar problems with language, which led her on a journey into Biblical translation. Working with an online resource that allowed her to compare more than fifty English translations, she ended up choosing more than a dozen sources from which to work.

The images at the library, also compiled in her book Song of Songs: The Bible’s Great Love Poems in Calligraphy, include the entire text of Song of Songs from a variety of translations that prioritize clarity over archaic language. She hopes that her design is similarly accessible.

“The viewer should be able to read it aloud and not worry about the design at all,” says Shepherd, and although she references the history of calligraphy from medieval illuminated manuscripts to art deco typography, she says she’s not “aiming for a historical look. I had to really guard against that. People always love to see something they can identify from a certain period.”

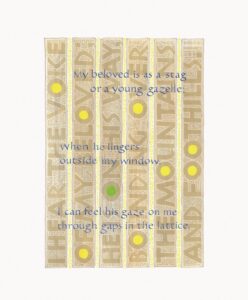

Despite Shepherd’s reservations about approaching the work with an eye toward history, one can’t help admiring her use of modernist aesthetics in the large, blocky letters from an image titled II: 8-9 (the titles correspond to the chapter and verses of the text). Once the viewer gets beyond the initial stylistic intrigue, it’s apparent that an engagement with the thematic content of the passage is what motivates Shepherd’s approach to lettering and imagery. Form and content merge seamlessly.

Her content is the text taken from scripture: “My beloved is as a stag or a young gazelle; when he lingers outside my window, I can feel his gaze on me through gaps in the lattice.” In her book, she comments on the text in each image and describes her decision-making behind each form. Here, the vertical strips of text evoke the form of lattice and she describes the “O”s scattered throughout the text as “stylized knotholes.”

“I filled their centers with soft yellow to imitate light shining behind a shutter,” she writes in her commentary.

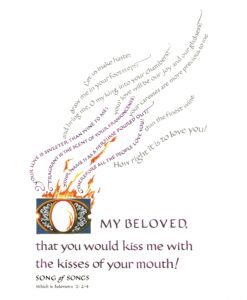

In another image, I: 2-4, Shepherd draws the viewer’s attention to one portion of the text with oversized lettering reading “O My beloved, that you would kiss me with the kisses of your mouth!”

“I think of calligraphy as sequential,” says Shepherd. “A calligrapher has a lot of control over what you see first.” Smaller snippets of text, like the passage “Your name is a perfume poured out,” snake upward from the opening “O,” which is encased in an object that appears as a burning altar. The serpentine, rhythmic lines of words rising evoke the earthy sensuality in the book.

Shepherd attends a Unitarian church but doesn’t describe herself as a religious person. “This book is as close to secular as you can get,” she says. “There’s no mention of God, and Solomon’s name appears in three places, but it’s not about him or his words.”

She was intrigued by the young woman’s voice, which dominates the text and boldly proclaims her sexual desire. Throughout history, the book has been read as a reflection on love while also being understood as a metaphor for God’s relationship to Israel (a Jewish reading) or Christ’s relationship to the Church (a Christian reading).

Despite her longstanding connection to the text, Shepherd is ready to leave the Song of Songs behind.

“I’m so done with this project,” she says. In addition to the Wellfleet library exhibition, the work has been shown at Yale Divinity School and Sarah Lawrence College, where Shepherd first learned calligraphy as a student in the 1960s. “I had the right teacher at the right time,” she says. “It was a colossal fluke.”

She’s wrapping up her latest project, a book about American alphabets. “Book projects seem to be all I know how to do,” says Shepherd, who has created nearly two dozen books, including her introductory text Learn Calligraphy. She attributes her ability to teach others to her own struggles with calligraphy.

“I’m not very good at it naturally,” she says. “I’ve really had to work at it.”

The Bible’s Great Love Poems in Calligraphy

The event: A show of original letter art by Margaret Shepherd

The time: Through Nov. 3

The place: Wellfleet Public Library, 55 West Main St.

The cost: Free