The celebrated poet Brendan Galvin of Truro died on Aug. 17, 2023 at Cape Cod Hospital. The cause of death, confirmed by his daughter, anthropologist Anne Galvin, was a heart attack. He was 84.

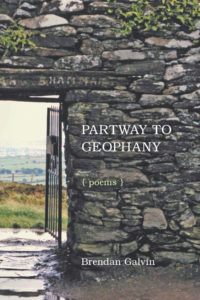

A National Book Award finalist for Habitat (2005) and winner of two National Endowment for the Humanities fellowships and a Guggenheim fellowship, Galvin was the author of 19 books of poetry in addition to over 500 poems in the Atlantic, Harper’s, Paris Review, the Nation, and the New Yorker. He won the O.B. Hardison Jr. Poetry Prize of the Folger Shakespeare Library, among many other prizes, and was emeritus professor at Central Connecticut State University.

In his review of Galvin’s Ocean Effects, Russ Kesler wrote that “reading these poems, we understand that the speaker is … someone for whom life without a steady diet of accomplished interaction with birds and trees and all manner of landscapes would not be complete.”

In “Great Blue” (1990), Galvin wrote, “Often,/ around certain backwaters/ like the ponds behind the oyster shacks,/ I hope for a heron,/ and sometimes I’m granted/ that wood-silver,/ crooked stick, channel-maker effect/ of the loosened neck,/ and that silence, humped like/ an overburden of experience,/ the weight it hauls in flight/ from river to pond above a highway/ when I look up at the mere/ abstract silhouette bird but am taken/ by the dragged beat of wings/ translucent at their tips.”

“I continue to write about the natural world I live in at my home in the woods above a Cape Cod salt marsh,” Galvin wrote, and “I accept the fact that my poems are ‘under peopled,’ but am not perplexed by it.” He added, “In many respects I’m a private person to whom the politics of literary reputation seem both a waste of time and an appalling example of our present-day lack of shame.”

Galvin’s poetry effaces the ego of the poet, doing the hard work to render what is palpable in the nature that surrounded him.

Although critic Ron Slate referred to Galvin as “the sneering recluse on the dunes, the barnacled misanthrope,” he also wrote that Galvin is “deeply appreciative of and moved by what flies or crawls or swims through his gaze. His care is genuine. His poetry, large in spirit and ambition, asks for reverence. I always give it gladly.”

Brendan Galvin was born in Everett on Oct. 20, 1938. His father, James Galvin, was a mail carrier, his mother Rose (McLaughlin) Galvin, a hairdresser. His childhood, daughter Anne said, “was rough and tumble.” When he was young, he “tarred roads and worked in the meat department of the A&P,” she said. He was also quite athletic.

Brendan played football at Malden Catholic High School, where he also began to experiment as a writer. “I remember your dad telling my classes that his fascination with words began with the nuns assigning paraphrases of scripture in high school,” a friend told Anne. “He realized that words could have multiple meanings.”

“In high school,” Brendan later wrote, “[I] received my first rejection when the faculty advisor to the student newspaper didn’t believe I’d written the poems I submitted. I was a tackle on the football team, and I think he thought I took them from someone on the bus.”

He majored in biology at Boston College, where “I sometimes wrote at the back of a laboratory while my peers cut into a turtle’s plastron to get at its terrified heart,” he later wrote. “Biology gave me a vocabulary I use in my poems without self-consciousness, so it’s not unusual for me to use a word like ‘meniscus.’ ”

He was accepted in dental school but decided to pursue a master’s in English at Northeastern instead. That decision, Anne said, perplexed his working-class parents, who were excited at the prospect of a doctor son.

Brendan earned an M.F.A. at UMass and completed his Ph.D. in 1970 with a dissertation on Theodore Roethke.

At UMass, Brendan met Ellen Baer, the daughter of German-Jewish émigrés, at a party in a peach orchard. She was an undergraduate and a single parent. They married in 1968. In place of an engagement ring, they decided to buy some land and build a house in Truro.

Life as a poet and an academic posed some problems for Brendan’s commitment to place. He took his first academic job at Slippery Rock College in Pennsylvania in 1968 before accepting a post at Central Connecticut in 1969, where, apart from visiting writer-in-residence and professor positions, he spent most of his career.

“We would spend our time during the academic year in Connecticut,” Anne said, but during the summer, semester breaks, and weekends long and short, “we were always in Truro.” The tools of his trade — inspiration, pen, and paper — were always at hand.

“My father,” Anne said, “was a tough guy.” He also had a sense of fun. “We went to Limerick, Ireland together,” she recalled, “and as we drove toward the town, we made up limericks.

“My father could be sharp and hard at times,” Anne said. “He expressed his feelings in his writing.”

His book Winter Oysters (1983) was short-listed for the Pulitzer Prize, and Saints in Their Ox-Hide Boat (1992) was designated a Choice Outstanding Academic Book by the American Library Association.

His narration for the film Massachusetts Story, a documentary on offshore drilling, received a first prize for documentary at the New England Film Festival.

“Galvin,” Peter Makuck wrote, “would like us to see, smell, hear, taste, and feel the world that is always there, moment by simple moment, a world replete with epiphanies of the common place.”

He is survived by his brothers, Bill, Terry, and Kevin, all of Wellfleet; daughter Anne Galvin and husband Harold Butler of Brooklyn, N.Y.; son Peter Galvin of Norton; and grandchildren Gwen, Owen, and Maddie.

He was predeceased by his wife, Ellen Baer.

Services were scheduled for Aug. 23 at the Chapman Funeral Home in Harwich, with burial at the Methodist Cemetery in Truro.

Donations in Brendan’s memory may be made to the Truro Police Association, P.O. Box 808, Truro. They should be labeled “In Memory of Brendan Galvin, with thanks to the Reassurance Program.”