It happened one evening at Studio 54: Halston entered the legendary nightclub and was about to check his coat and fur hat. Ten feet away, Bobby Miller spotted his prey and sensed when to pounce.

“I knew that the minute he took his hat off, he was going to turn around and fix his hair,” says Miller. In the photograph Miller captured, Halston’s suave grin speaks volumes. Looking at the photo, Miller’s grin speaks volumes, too. “Nobody else has that shot,” he says.

Armed with a 35mm camera, the watchful eye of a paparazzo, and a preternatural sense of knowing exactly when to click his shutter — the ability to seize what photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson called “the decisive moment” — Miller has been taking pictures of the famous and infamous (and occasionally the not-so-famous) for more than four decades.

But fame isn’t the only criterion for subjects that catch his eye. “I am always drawn to the unusual, the black sheep, the misfit, the clowns and freaks who don’t quite fit in,” he says.

It’s a predilection that reflects his artistic training. Miller studied with Lisette Model, the Austrian-born photographer whose street photography influenced Diane Arbus. And through looking at the work of Arbus, whose photographs often presented extreme outliers of the human condition, Miller gained confidence in staking out his own territory, which came to include the glitterati of New York City during the golden years of disco.

Miller exhibited his photographs in nightclubs in his early days. His current show at AMP Gallery is a more organized affair. For “Bobby Miller: A 45-Year Retrospective,” he and AMP owner Debbie Nadolney selected approximately 45 images from the 150 Miller culled from his archives.

Miller is at the gallery dressed in white from his high-top sneakers and socks to a V-neck T-shirt, accented with black beads and dark sunglasses. His long blond hair, parted in the center, has remained his trademark since his days as a runaway hippie from Washington, D.C. — where he was born during the Eisenhower years — to the San Francisco of flower children and psychedelic rock.

He chats with gallery visitors who want to know more about who’s on the walls. Not surprising for a published poet and performer — his work has been included in collections like The Outlaw Bible of American Poetry — Miller is an engaging teller of stories that feel like capsules of cultural histories.

Many take place in New York City in the 1970s. Miller tells the story behind his portrait of Edith Bouvier Beale (a.k.a. Little Edie), a celebrated debutante turned recluse who became the subject (along with her mother Big Edie Beale) of the 1975 documentary film Grey Gardens. The film had just been screened at the New York Film Festival.

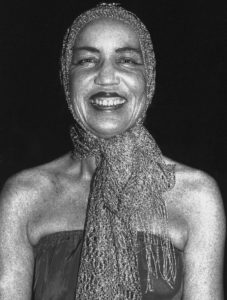

“I got her just as she came in the door,” he says, “and I took one shot before her publicity people pushed me away.” He went home, developed the film, and found that the single shot he took perfectly captured Beale’s glittering scarf and expansive smile, happy at last to be the center of attention.

Another photo taken the same year of a relaxed-looking Andy Warhol chatting with Steve Rubell, the co-owner of Studio 54, now reads as a metaphor of hedonism and imminent catastrophe: Rubell, who went to prison for tax fraud, later died of complications related to AIDS.

During the same years that he was capturing the glittery habitués of the uptown social whirl, he was also part of the punk and alternative cultural scene exploding in lower Manhattan. A suite of photos from 1976 on the second floor of the gallery depict Jim Jarmusch, Cookie Mueller, John Waters, and Jerry Hall, each on the cusp of celebrity. The portraits capture moments in their subjects’ lives in a way that feels disarmingly casual and profoundly prescient at the same time.

Miller’s irresistible image of writer and underground muse Mueller is a case in point. Captured on a dance floor, her features and jewelry appear sculpted with light and seem to reflect her inimitable spirit.

It was Mueller’s longtime partner Sharon Niesp who kept urging Miller, then living in New York, to come to Provincetown. “I said, ‘What’s in Provincetown?’ ” Miller recalls, laughing. “And she said, ‘A bunch of fishermen and laid-back hippies.’ ”

It took over two decades, nudged by the events of 9/11 and the encouragement of his own partner John LeClair, who was already living in town, for Miller to pack up his life in New York and become a year-rounder. He continued to work just as prolifically and began to self-publish various collections of work, including two volumes of portraits of town personalities under the title Ptown Peeps.

After two decades in Provincetown, Miller and LeClair moved to Great Barrington, where Miller continues to make and show new work. But with the imminent closing of the AMP gallery, this is a rare opportunity to appreciate the people and moments that Miller freeze-framed for posterity.

Peeps Show

The event: Bobby Miller: A 45-Year Retrospective

The time: Through Wednesday, Sept. 7

The place: AMP Gallery, 432 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free