The Moon is always with us. Even when we can’t see it, it’s there, gently tugging on our oceans and causing our tides. It hasn’t always been with us; the Moon formed a few hundred million years after Earth did. But over the 4 billion years since then, it’s proved itself to be a loyal companion. And the Moon will be with us until the end, when a swollen red Sun swallows the inner planets, about 5 billion years from now.

The story of the Moon begins with the creation of our solar system. About 4.6 billion years ago, a star exploded as a supernova. That explosion sent a shock wave into the surrounding interstellar medium; the shock wave eventually collided with a vast cloud of gas and dust, maybe 65 light years across. That impact created areas of higher density within the cloud; higher density means higher gravity: the denser areas began to draw material in.

Hundreds of these relatively dense knots of gas and dust, called pre-solar nebulae, formed within the cloud; each would become a star. We’ll zoom in on one of them. There’s nothing special about it, at least not yet. But there will be. This one will become our Sun.

The temperature of this pre-solar nebula soared as gravity compressed it further. The process accelerated in a positive feedback loop of increasing density and increasing gravity. It had become a protostar, surrounded by a disk of rotating gas and dust. Finally, the density and temperature exceeded a critical threshold; hydrogen atoms began to fuse together, creating helium atoms and releasing enormous amounts of energy. A star was born: our star, the Sun.

But the creation process was not finished. That disk of rotating gas and dust still surrounded the Sun. Molecules and dust within the disk collided as they orbited the nascent Sun. Sometimes they rebounded, and sometimes they stuck together. As the particles accreted and grew larger, their gravity grew stronger. The larger pieces attracted smaller ones, creating planetesimals, the building blocks of planets. They collided, grew, and formed planets, some large and some small, and of varying composition, depending on how far from the Sun they formed.

What about the Moon, you ask? Hang on, we’re nearly there.

The early solar system was a rough place. The eight planets — Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune — were not alone. The leftovers, the planetesimals that hadn’t become part of any planet, still hurtled about. These varied in size from pebbles or snowballs to objects as big as a small planet. Some were ejected from the solar system by gravitational interactions with Jupiter, the largest planet. Some settled into stable orbits; we now call these asteroids, comets, and dwarf planets (Pluto is one of these). And some collided with the planets.

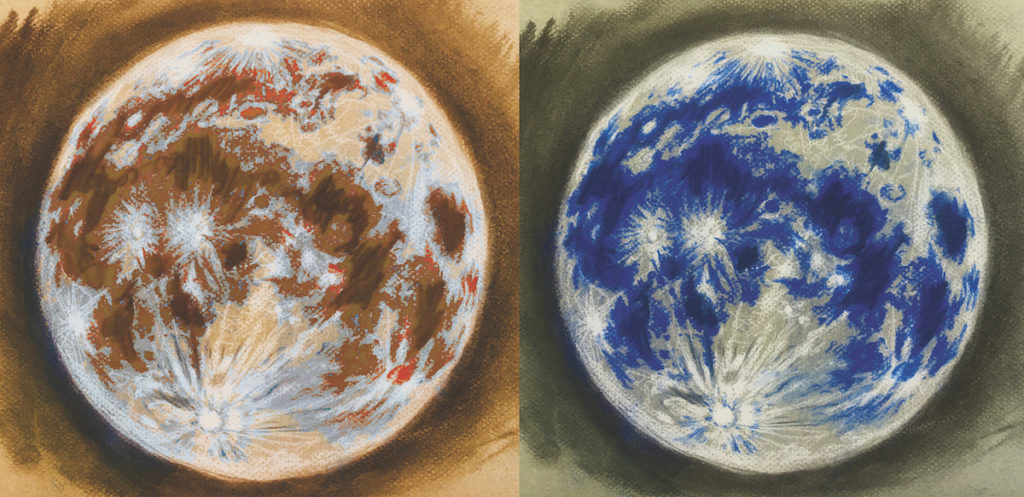

A large planetesimal, about half the size of Earth, struck us a glancing blow about 4.3 billion years ago. But even a glancing blow between two such large bodies was cataclysmic, completely melting Earth’s surface and launching a huge amount of molten rock and vaporized material into orbit. The debris formed a ring around Earth, much like Saturn’s rings; it would have been a lovely sight from the surface — if the surface had not been a hellscape of lava seas and poisonous gases at the time.

But our ring did not last long (Saturn’s rings will also not last forever, but that’s another story). The accretion process played out once more, this time in Earth’s orbit. Over hundreds of years, which is a very short time in astronomical terms, the collision debris coalesced — small pieces became larger, the larger pieces collided and merged, and our Moon took shape.

This intense early period of impacts gradually tapered off as the surviving denizens of the solar system settled into mostly stable orbits. On Earth, plate tectonics and wind and water erosion have erased those early impact scars, including the impact that nearly destroyed us, and which gave us our Moon. But the Moon’s cratered surface has preserved a record of those violent years and more recent impacts. We’ll focus on that surface next time.

Until then, go outside on a clear night and look again at the steady companion that lights our night sky. Clear skies!