WELLFLEET — The house teetering on a coastal bank at 1440 Chequessett Neck Road is for sale again, less than two years after it was purchased by New York attorney John G. Bonomi Jr. The listing came less than two weeks after a judge upheld the Wellfleet Conservation Commission’s ruling that the owner of the house could not build a rock revetment to protect the house from erosion.

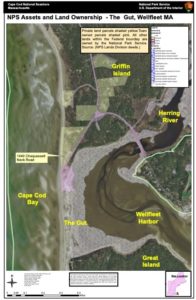

The 5,153-square-foot house overlooks Cape Cod Bay just north of the narrow strip of sand known as “the Gut.” It has been the subject of controversy since it was built by Mark and Barbara Blasch in 2010. The coastal bank has been eroding by 6 to 7 feet per year, according to a 2020 estimate. The foundation of the house is now within a few feet of the edge.

In December 2018, the Blasches requested permission from the Wellfleet Conservation Commission to build a 241-foot rock revetment to protect it from erosion and were turned down. They appealed, and in February 2021 their plan was rejected again. The 2021 decision cited both the feasibility of other solutions, such as demolishing and rebuilding the house further back from the bank, and the possible damage that a revetment might create to the natural flow of water and sand.

In February 2019, following the first denial, attorney James Hoeland filed suit against the conservation commission as a trustee of the Blasches’ family trust. This suit was filed in Barnstable County Superior Court. When the Blasches sold the house in December 2021 for $5.5 million, the new owner, Bonomi, opted to continue the suit.

On Oct. 2 of this year, Judge Michael K. Callan affirmed the conservation commission’s decision that a revetment would violate wetlands protection laws. Hoeland appealed Callan’s ruling on Oct. 16 on behalf of the family’s trust.

The house was listed for $4.5 million on Oct. 11, a million dollars less than Bonomi purchased it for. The listing agent is Michael Degnan, cofounder of Realty Executives of Cape Cod, based in Hyannis. It is unclear whether the ruling played any role in the listing. Neither Degnan nor Bonomi were available to comment on the record.

John Cumbler, a former professor of environmental history at the University of Louisville and a member of the seven-person Wellfleet Conservation Commission, said that building a house in that location “guaranteed a problem” because of the geography of the area. According to Cumbler, the Gut is what is known as a nodal point. High velocity water hits the area and splits, flowing both north and south and carrying sand with it. This flow pattern means sand is being pulled away from the Gut without being replaced. It’s inevitable, he said, that the coastal bank there would be eroded.

According to Cumbler, one of the problems with building a revetment is that it would disrupt the natural sedimentation process. This could result in unnatural sand buildups or deficits.

“If you build a seawall there, that’s going to change everything in ways we have no way of predicting,” he said.

What would likely happen, he said, is that the high velocity water would simply erode portions of the bank on either side of the seawall. Before long, it would become “like a fork in the middle, with water all around it,” before slowly turning into an island. This would be, Cumbler said, “a bizarre situation for the house.”

The conservation commission has approved other measures to prevent the Chequessett Neck Road house from falling into the bay. In December 2020, the commission approved the Blasches’ request for emergency certification to pile biodegradable sandbags at the base of the bank. Cumbler said that this plan, despite requiring repairs at one point since its implementation, “turned out to be far more successful than I thought it would be.”

From 2013 to 2021, the Blasches dumped large piles of sand annually in front of their property. This “sacrificial sand” was meant to be washed away by waves, theoretically preventing the erosion of the bank. From 2013 to 2019, 5,000 cubic yards of sand were dumped at the property, all of which was washed into the sea.

The Independent reported that some oyster farmers have claimed their grants were buried by sacrificial sand of the kind that has been dumped at the former Blasch house.

Despite the grim outlook for the house, Cumbler emphasized that there are other short-term solutions to the erosion issue besides building a revetment. The lot is large enough, he said, that the owner could move the house back on the property, although it may have to be reduced in size. “That would give them significantly more time on the property,” he said. He also suggested “aggressive” planting of beach grass on the bank; its roots can help hold sand in place and prevent erosion.

Ultimately, Cumbler said, “Whoever owns that house has to understand that nature is going to take its course.”