There’s a big black hole at the heart of our Milky Way galaxy. It’s called Sagittarius A*, and in May scientists working on the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) project released an image of it for all to see.

The fact that this big black hole exists may sound dramatic, but it’s not news. Most galaxies have black holes like Sagittarius A* at their centers. These are the supermassive type of black hole, as opposed to the garden-variety stellar types. A stellar black hole may have a mass equivalent to 10 or 20 stars like our Sun. A supermassive black hole has a mass equivalent to millions of suns.

Having a picture of Sagittarius A* is what’s exciting. More than 300 scientists at institutions around the world collaborated to produce the image, using a global network of telescopes, sophisticated image-processing software, and lots of hard work.

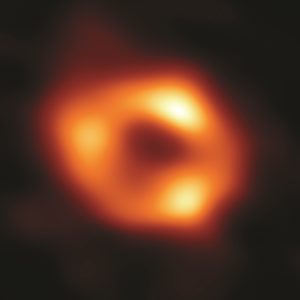

The EHT image we got in May of our supermassive black hole shows a dark central area, surrounded by a brightly glowing ring. But what exactly are we looking at?

It’s impossible to directly image a black hole. They are objects so massive and so dense that their escape velocity — the speed required to escape the pull of an object’s gravity — exceeds the speed of light. And since nothing can travel faster than light, nothing that ventures too close to a black hole ever escapes. No matter, no radiation, no information of any kind. There’s nothing we can photograph.

Black holes have limits, however. As Sir Isaac Newton posited, gravity follows an inverse-square law: the force of an object’s gravity is inversely proportional to the square of the distance from that object. Put another way, the force of an object’s gravity decreases quickly over distance. As the force of gravity decreases, so does the escape velocity.

The distance from a black hole at which the escape velocity falls below the speed of light is called the event horizon.

You can skim as close to the event horizon as you like, provided your spaceship can travel fast enough, and still get away. (We’ll ignore the issue of enormous tidal forces stretching you like taffy.) But the moment you cross the event horizon, you are lost. Your radio signals, traveling at the speed of light, will approach the event horizon, trying to reach us to tell what things are like on the other side, or where you left your Bitcoin recovery phrase. But the radio signals will bend away before they can cross the horizon, pulled back in a long arc towards the black hole itself, there to face the ultimate cosmic annihilation. This will be your fate, as well.

The EHT image reveals the black hole by its absence. The apparent void of the central dark area marks the boundary of the event horizon. Within lies the black hole. Nothing reaches us from there.

The brightly glowing ring is the accretion disk — matter orbiting the black hole that has not yet crossed the event horizon. It glows because the gas and dust are very hot. As the orbiting matter falls closer and closer to the event horizon, it travels faster and faster, like a swirling whirlpool. Friction and powerful magnetic fields create incredible heat, which rises until the gas and dust flash into incandescence, emitting high-energy radiation across the spectrum. It is the doomed matter’s final farewell before it crosses the event horizon.

The image of Sagittarius A* is more than an evocative portrait of a cosmic giant. Details in the image have provided further confirmation of Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Not that the theory needed more confirmation — the GPS navigation in your smartphone works just fine, doesn’t it? You can thank Einstein for that.

Data obtained from the image has also helped scientists match theory to observation, improving various models related to high-energy physics, astronomy, and cosmology. EHT’s work has increased our understanding of the world around us and, perhaps more important, has pointed the way to new questions and new mysteries to investigate.

There’s something thrilling about staring down the maw of a monstrous black hole that devours entire stars for breakfast. Clear skies!

This column was inspired by a reader who, after reading about the latest EHT image in the news, asked if I would write about it. (Thank you, Siân!) I love hearing from readers. If there’s an astronomy topic you’d like to know more about, you can email me at [email protected].