EASTHAM — Bats took over town hall last week, displacing town employees and moving last weekend’s early voting for the Sept. 1 primary election outdoors. Town Administrator Jacqui Beebe said on Monday the bats had relocated themselves after an animal removal contractor installed baffles at their entry points.

“The bats can leave to get food but can’t get back in,” she said.

While employees could return to work in the building Monday, the town hall remains closed to the public due to the pandemic.

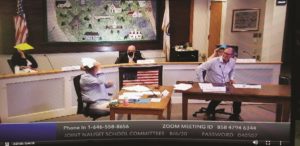

One bat made its first public appearance on Aug. 6, during a live-streamed meeting of the joint Nauset school committees, swooping around the meeting room as attendees ducked, covered their heads, or, in the case of Supt. Tom Conrad, laughed.

“We’ll just step out a second and see if we can bring the bat with us,” said Conrad. The meeting resumed a few minutes later, sans bat.

Although it adjourned from the meeting that evening, the bat likely didn’t vacate the town hall, as more bats appeared in town offices the next day.

“That bat had friends and relatives,” said Beebe.

Zak Metz, executive director of the Birdsey Cape Wildlife Center in Mashpee, said bats often roost in warm locations like attics to raise their families but are forced down into the lower levels when it gets too hot. Birdsey is the Cape Cod branch of the New England Wildlife Centers, one of only two centers in the state currently authorized to treat bats.

Bats have just one pup at a time, said Metz, which take up to 40 to 50 days before they fledge, usually around September or October. While a bat’s immediate family may be small, its extended family can be large.

“A lot of species will roost together,” said Metz. “You can get whole colonies in one spot.”

Cape Cod National Seashore studies of bats within the park have documented eight different species, the most common being the big brown bat.

Jeoffrey Sander, chief of natural resource management at the Seashore, said the park service across the country has been part of an effort to monitor declining bat populations caused in part by white nose syndrome, a fungus that typically affects bats that use caves as their hibernacula — or winter homes.

Bruce Davis, owner of A to Z Animal and Pest Control, said he usually receives about 25 calls for bats each year in his coverage area, from the Cape Cod Canal to Eastham, and has gotten a little over half that number so far this season. As bats are a protected species, removing them means getting the invaders to leave of their own accord through one-way tubes and blocking other access points to prevent their return.

“All you can really do is scoot them,” said Davis. “They usually go to the neighbors. I’ve done three houses on one street.”

Wherever they go, bats are an important part of the ecosystem, consuming large numbers of insects each night, according to the Seashore’s bat monitoring report.

Because they seem to host viruses without being sickened, bats are currently the subject of scientific interest when it comes to understanding how coronaviruses work and how they might be controlled. In what scientists call a dangerous precedent, the National Institutes of Health’s research on the subject was recently halted by the Trump administration for political reasons, according the Pulitzer Center.

Locally, humans have at least one big reason to get along with bats. As Sanders, of the park service, noted, “Bats play a really significant role in controlling the insect populations.”