WELLFLEET — David Wright, the curator at the Wellfleet Historical Society and Museum, has over the years compiled a list of houses in Wellfleet that had been moved from their previous locations, most frequently Billingsgate Island and Bound Brook Island.

Walking around the center of town with his list in hand, I admired one of these homes on Baker Avenue for its historical details, including its antique glass windows and shingles. Painted white, it sits among shrubs and budding lilacs bushes, seemingly growing from the landscape. The house, however, is a transplant, floated across Wellfleet Harbor in 1860 from Billingsgate Island, which is now a mere sandbar occasionally coming into view at low tide.

“People are fascinated by the mystery of it, the Atlantis quality of it,” says Wright of the submerged island. Its disappearance, which Wright says was due to erosion, was something people had no control over. One thing they could do, though, was move their houses “in accordance with the new reality.”

Ed McPartland, a retired builder from Wellfleet, recalls encountering traces of Billingsgate’s past when he was renovating a house in the center of town 12 years ago. While replacing a rotten window he found “neatly folded newspapers tucked under the trim boards as a weather barrier.” Those New England abolitionist newspapers hadn’t been touched since the 1850s, he said.

Roman numerals chiseled into the joints of beams signified where mating pieces would match up, McPartland says, revealing the lengths the owners went to, piecing their home together, beam by beam, to resettle on more stable ground.

This house, along with others on Main Street and Commercial Street, helped to establish a new downtown. “The town center as we know it was a 19th-century invention,” says Wright.

Wellfleet had other islands, including Griffin and Bound Brook, which, unlike Billingsgate, merged into the mainland through the accretion of silt in the waterways around them. The farming settlements on these islands were oriented toward Duck Harbor.

Changes in the environment shifted commercial activity to Wellfleet’s current harbor in the mid 1800s. That’s when “people wanted to coalesce around the new harbor and all the maritime trades set up shop on Commercial Street,” says Wright. “But the town was piss poor, and wood was scarce. So, it made perfect sense to transport the houses.”

The Billingsgate houses of Wellfleet are not the only ones that were moved as land and families’ circumstances changed. Many of the houses lining Commercial Street in Provincetown were originally built on Long Point, at the very tip of the Cape. Eastham’s windmill on the town green was built in Plymouth about 1680, moved to Truro in the 1770s, and then to Eastham in 1793.

They’re moves that tell stories, or surely could. My late grandparents’ home was floated over from Wellfleet’s Great Island, eventually landing in Chatham. Family lore has it that the house was formerly a tavern.

Wright says the moves tell two kinds of stories: “One is permanence and perseverance, and the other is flexibility.” Admirable stories, he adds. “ ‘I’m meant to be here, I’ve been here a long time, and I’m adaptable; I can change with the times.’ It’s a pretty good way to think of oneself,” he says.

One wonders if living in a house with such a history might inspire a certain openness to change. In South Wellfleet, Katherine Alford and her husband, Robert S Johnson (she writes about food and he takes photographs for the Independent), live in a home perched on a hill overlooking Blackfish Creek, moved to its current location in 1910. Uncertain where it came from, Alford believes it may be from Billingsgate like other houses in the neighborhood.

Approaching the home from the street, visitors find there’s no front door. “Perhaps they swung the house around,” says Johnson, noting that a door overlooking the water — impractical for anyone approaching the house from the road — might have been a logical entrance in another time and place.

Living here, Alford says, “you understand how a house becomes a constant evolution.” Commandeered by the Coast Guard during World War II, the house’s cupola was used as a radio station, transmitting signals across Cape Cod Bay. Now the couple uses the space as a meditation and reading room.

Back on Commercial Street, Bob Henry, a Wellfleet artist of renown, lives and works in a house that was built as a schoolhouse in Truro in 1847. He bought it in 1999 with his late wife, the artist Selina Trieff.

“In the 1860s, it was floated down here from Truro,” Henry says. “At that point this was a deep sea,” he adds, referring to Duck Creek, the tidal inlet across from his home. The former school’s attic now serves as Henry’s studio, a workspace crammed with hundreds of paintings overflowing from storage racks.

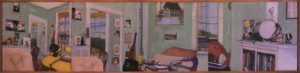

Henry created a gallery space on the ground floor, which was once a dry-goods store. The second floor serves as the main living space. It’s visually busy, the walls filled with artwork, mostly from friends. There’s a long figurative sculpture, seemingly constructed from driftwood, cutting through the dining room. The invented figures of his paintings populate a series of triptychs hanging close to the ceiling in the living room, crowded by other paintings, stacks of books, musical instruments, and enough chairs for a party.

“There’s a disorder to the room. Which I like,” Henry says. “It’s visually interesting not to have everything set in place.” He adds that he’s lazy about homemaking, so sees his ever-changing surroundings as “celebrating my non-bourgeois existence.”

Over the winter, Henry has been working on a series of paintings, “stuttered panoramas” he calls them, depicting his living room and view of the Mid-Cape lumber yard and Duck Creek beyond. “I like the view out the window, the mix of the industrial world, interior world, and natural world,” he says.

The paintings recall early Renaissance paintings of architectural scenes. They merge drawing and painting, the hard lines of the architecture contrasting with more painterly moments in the landscape, such as the silvery stroke of paint depicting the water beyond his home. He describes the room as “a visual autobiography.”

The paintings reiterate the question of change raised by all these floating houses. In them, the room becomes a record of a particular life and particular vantage point, with the windows opening to the world beyond in all its complexity as a place of industry and natural beauty.

Aware of the building’s history and the limits of his time within the space, Henry draws parallels between the life of his home and his own mortality.

“There’s something about being 88. You realize you’re transient on this Earth,” says Henry. Painting his house at this point in history “seemed right to me,” as if to say, “ ‘Here’s a record of what it was when I was alive and using it.’ ”