In the quiet valley town of Missoula, Mont., sprawled at the feet of five mountain ranges, Bill Bowers’s parents — both descended from generations of ranchers and farmers — did the improbable: “They grew a gay mime,” says Bowers.

Bowers, born in 1959, has been a full-time professional mime for more than two decades and an actor for longer: he’s played Zazu in The Lion King on Broadway, appeared in Two Weeks Notice, a 2002 rom-com starring Sandra Bullock and Hugh Grant, and acted on stages across the country. As a child, before he knew what mime was, he told stories with his body, performing only for himself, he says.

The youngest of six, Bowers grew up shy and closeted in a place where “there’s a lot of nature and not a lot of people,” he says. Three “circles of silence” commanded his early life: the silence created by the physical distance between people in western Montana, the absence of “deep talk” — “people tend to leave each other alone in Montana,” he says — and the lack of dialogue about being gay. “There was absolutely no conversation to be had about who I thought I was,” says Bowers.

Now, he says, “I’m interested in how silence operates in the world for all of us.” At the Provincetown Theater, June 26 through 28, Bowers will perform his one-man autobiographical play, It Goes Without Saying, which premiered off-Broadway in 2006.

The play — which, despite its title, includes plenty of spoken lines alongside “a huge amount of mime” — is an artful compilation of true stories from Bowers’s life. Originally, he says, the idea was to tell funny stories about “crazy experiences” and “weird jobs” he’s had. But he soon realized the play was something more.

There are stories about bullying and isolation. The play includes scenes from Bowers’s experiences during the 1980s AIDS crisis in New York City, where he still lives. His partner died of AIDS then. In working on the play, Bowers says, he realized “how much silence was involved in that experience.” There was the “Silence=Death” poster from the time, he says, and the echoing silence of politicians and lawmakers. At the end of his partner’s life, says Bowers, his partner lost the ability to speak. “We were communicating, but it wasn’t with words,” he says. “Silence just seems to rise up and up again for me.”

There are funny tales, too. For seven years in the ’90s, Bowers was Slim Goodbody, a character also known as “The Superhero of Health,” created by actor and writer John Burstein in 1975. Dressed in a spandex bodysuit painted with biologically accurate internal organs, Bowers performed a sort of musical vaudeville show on television and in live performances nationwide.

It Goes Without Saying is ultimately about “the comfort of silence and the challenge of silence,” says Bowers. The play isn’t a new one. But Bowers says over the past year “it’s been having a second life,” perhaps because mime isn’t just an art. Bowers says it’s a political tool, a way to speak your mind without saying a word — a popular concept under authoritarian rule. “It’s been in trouble with the law throughout its history,” he says.

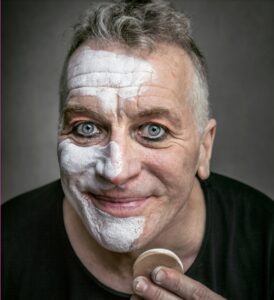

Bowers defines mime, which dates back to the ancient Greeks, as “a way of telling a story without using words.” It’s different from “pantomime” — the better-known style of storytelling in which a performer, often in whiteface, creates and interacts with imaginary objects. The art of mime is more about space: “Using your body in space to evoke images, ideas, and feelings.”

In a story involving water, a pantomime might involve pretending to sit in a boat and put bait on a fishing pole. “If I were doing a mime about water,” says Bowers, “I could evoke the movement of water. I could be a fish in the sea.”

Bowers, who got his M.F.A. from Rutgers University in 1984, teaches at NYU, the Stella Adler Studio of Acting, and the William Esper Studio. He tells his students to consider the difference this way: “Pantomime is like realism; a realistic portrait. Mime is impressionism; like Van Gogh.” His own practice involves some of both styles: his body flows through space, gathering the air and making it solid, then transfiguring it with the smallest gesture.

Much of the training Bowers has received and taught is based on the French mime Étienne Decroux. “He developed a vocabulary for the body,” says Bowers: the ways body parts can be isolated or move as a unit.

“We learned the alphabet when we were kids, so we could learn to write,” says Bowers. “Decroux’s is a physical vocabulary, which you can then use to create images and illusions.” Decroux, who observed in people the distribution of their weight and the exact sequence of their movements, didn’t call himself a mime, says Bowers. “He called himself a ‘furniture-mover.’ ”

“Mime can be a mirror,” says Bowers. “It can show us things about the world, how we feel about the world.” With his body, Bowers can make chaos or peace. The audience feels it, he says. Often, after shows, people will tell him they connected unexpectedly to some movement, some story. “One of the great purposes of art is that it’s humanizing,” says Bowers. “When you see a piece of art, you see yourself in it.” In silence, the reflection appears especially undisturbed.

In 1977, the legendary French mime Marcel Marceau came to Missoula for one night only. Bowers’s mother bought him a ticket. He went and was enchanted. Marceau moved with extraordinary grace, his dark eyes intense against his white face. “I thought, ‘This is what you can do in silence,’ ” says Bowers.

Bowers left The Lion King cast in 1999 after injuring his hands handling the puppet costume for Zazu. While recovering in the hospital, he saw that Marceau was embarking on a world tour in honor of his 80th birthday. Bowers spent the next three years traveling across North America, studying with the master.

Aside from an education in technique, Marceau taught him two main lessons. One was that mime is “living art,” says Bowers. “If we don’t teach it and perform it, it will disappear.” He took that to heart. “I’ve been on the road ever since.”

Marceau also taught him that “mime” is not the mime himself. “It’s the space between the mime and the audience,” says Bowers. “It’s a collaborative art.” For the art to exist, the audience also must imagine what isn’t really there.

In Missoula, his family had “no relationship to art,” says Bowers. Until he became an actor, most of his family had never set foot in a theater; his father had never seen a play. But Bowers feels that he has moved with quiet purpose. He’s always been a mime; he was born one.

“It’s funny how that happened,” he says, “seemingly out of nothing.”

Out of Thin Air

The event: Bill Bowers’s one-mime play, It Goes Without Saying

The time: Thursday through Saturday, June 26 to 28, 7 p.m.

The place: The Provincetown Theater, 238 Bradford St.

The cost: $55 at provincetowntheater.org