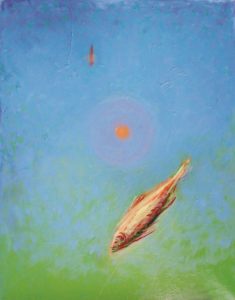

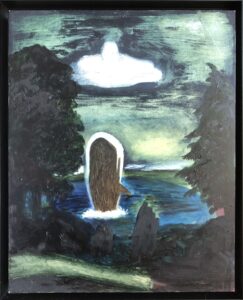

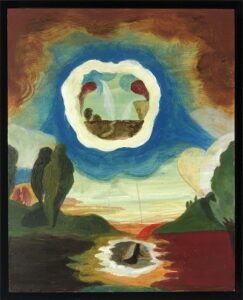

One of Polly Burnell’s most recent paintings, The Whale Dream (5 years before I came here), is of a whale that seems to be ascending from the water toward a single white cloud. Two black trees frame the moody scene like silent witnesses.

The painting is based on a dream Burnell had years before moving to Provincetown. At the time, she was living in Cincinnati running a bookstore. She had a burgeoning art career but had hit a block in her creativity. On the advice of one of her bookstore patrons, she visited a Jungian therapist.

“I didn’t want to see a therapist, but I went anyway because I was desperate to get some artwork done,” says Burnell.

The visit proved worthwhile. Burnell and the therapist discussed images, dreams, and the death of her father, which occurred when Burnell was five. The last painting she had made before her work was interrupted was of a blindfolded horse with no rider running across a stony, barren place.

“I realized all of the work was about grief, and that’s why I was blocked,” she says. “It was very profound to understand that the work was connected to something rooted in me.”

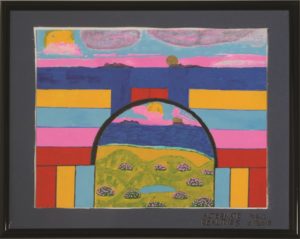

This experience opened a path forward and further attuned Burnell to her interior world, including dreams. Around that time, she had the whale dream. “In the dream, I was alone in a still place by a body of water,” she says. “A whale slowly came up and slowly dove back down.” In Burnell’s painting of this dream, the elements read as symbols. The whale, the cloud, and the two trees exist as characters collaged together in uneasy relation to each other rather than as parts of a unified whole. This visual language recalls Jung’s emphasis on symbols and archetypes, but in Burnell’s paintings, she employs objects, animals, and dreamlike places in a way that is less utilitarian.

Burnell’s paintings aren’t concerned with clarifying the mysteries of our subconscious selves. “If I could describe them, I wouldn’t paint them,” she says of her invented worlds. Burnell is after something that transcends language and rational explanation.

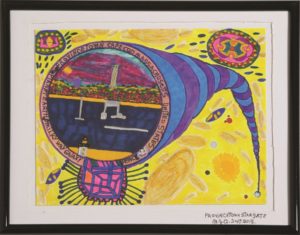

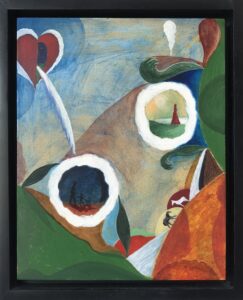

In The Dark Well and the Light Well, Burnell invents a range of worlds glimpsed through vignettes that punctuate the composition. At the bottom of the painting two horses gaze at each other, silhouetted in front of rounded hills. Farther up in the composition Burnell inserts narrative moments into bubble-like shapes that float through a space of abstract shapes. In one, a woman stares longingly at the sun. Everything here is topsy-turvy, narratives are suggested but there’s no throughline, and gravity feels negotiable.

Like dreams, Burnell’s paintings take snippets from our conscious lives and weave them together into nonlinear narratives. “I don’t necessarily believe things are linear,” says Burnell. And like our dreams, these spaces are completely convincing despite their impossibility.

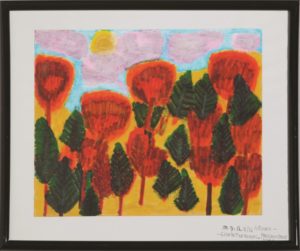

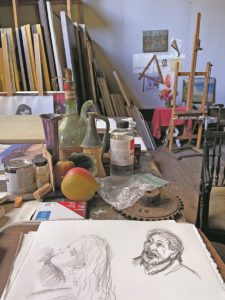

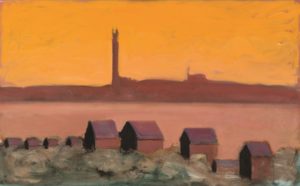

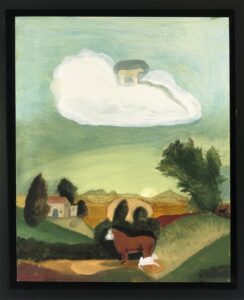

Burnell convinces us through formal conviction. She’s an astute student of art history, and her paintings reverberate with the inventiveness of European Surrealism; the earthy spirituality of American painters like Albert York, Marsden Hartley, and Albert Pinkham Ryder; and the mysticism of Sienese painting. Like many of the great artists she admires, her sense of color and composition is complex and obsessively considered, evidenced by surfaces that are scraped down, layered, and painstakingly nurtured into being. She conjures worlds with color palettes: in They are watching over you, she suggests a bucolic Italian landscape with muddy green foliage, an umber-colored haze, and a central cobalt shape.

In The Red Horse and Blue Mule, Burnell foregrounds the image with a pair of cypress trees that seem to unfold throughout the composition. Their serpentine forms echo in interlocking warm and cool shapes that build a dome-like space above the animals. Generally, Burnell’s process is one of slowly unfolding. Through the making of the pictures, narratives open up and spaces expand, like rabbit holes. “They’re like dreams, and they’re always shifting,” says Burnell. She works on her modest-sized panels over long periods, but the process is less about refinement and more about expansion.

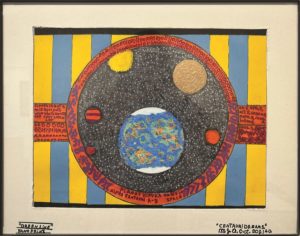

Part of Burnell’s intention is to expand beyond the limits of our experience as conscious human beings. “I’ve never done LSD or anything — I’m already tripping all the time,” she says, laughing. “I learned to have a sense of the mystical from a very young age.” She was raised in a Catholic tradition that emphasized liberation theology.

“I think our brains are too big,” she says. “I always feel like there’s a certain amount of tension between being a human being and a spiritual being. There aren’t words for what I’m talking about really, but what’s interesting is that when I’m out in nature, it’s just all balanced out.”

For all the profundity of Burnell’s art, it’s tempered by her rough-hewn surfaces and the diminutive scale of the work. Berta Walker, her gallerist, draws a parallel between her artwork and her unpretentious, Midwestern affect.

“Like her little paintings, she’s quiet but has a strong presence,” says Walker, who first met Burnell when she was a fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center.

Burnell came to Provincetown in 1986. After quitting her job at the bookstore and leaving Cincinnati to travel in Europe, Burnell met the artist Richard Baker in a youth hostel. They married and settled in Provincetown, where Baker had been a resident at the Fine Arts Work Center. After they divorced, Baker moved to New York, but Burnell stayed in Provincetown.

“I always had support here,” she says. “Berta has supported me forever and I’m just continuing to paint and live here.” In 1993, she was awarded a fellowship at the Fine Arts Work Center, which has remained an anchor for her.

The title of her painting of the whale suggests that the dream was a sort of premonition or prophecy. The image of a whale rising from the water is germane to Provincetown and charts her journey in a way that is nonlinear, located in a world that has one foot in the here-and-now and another in something more ambiguous — a space that could be alternately defined as spiritual, mystical, primal, subconscious, or universal.

It’s impossible to define or quantify these experiences, and yet somehow Burnell manages to both preserve the mystery of this territory and render it concrete in her small, unassuming paintings.

Dream Paintings

The event: An exhibition of works by Polly Burnell

The time: Through July 13

The place: Berta Walker Gallery, 208 Bradford St., Provincetown

The cost: Free