Obscured by trees, Rob DuToit’s Provincetown studio is easy to miss. Approached from the side, it appears as an innocuous whitewashed structure with a single door. But the odd angle of the roof indicates something out of the ordinary.

Designed by sculptor and architect Tony Smith in 1945, the studio belonged to the artist Fritz Bultman until his death in 1985. None of the walls are perpendicular to the floor — fine for a sculptor, perhaps, but problematic for a painter who wants to hang his work.

“It’s a little different,” says DuToit, who has installed false interior walls to solve the problem. He has occupied the space, which he rents from Fritz’s son, Johann, since 1988. It’s long enough to claim dominion, though he sometimes still feels like a guest.

DuToit grew up in Winchester, just outside Boston. His mother was an amateur painter “always taking classes,” he says. As an undergraduate at the University of New Hampshire, he was pre-med before switching to art. He graduated with an M.F.A. from Parsons School of Design in 1981. DuToit studied with Paul Resika in New York before coming to the Cape in 1985. He now lives in Truro with his wife, Janice Redman, also an artist.

DuToit’s scientific background has influenced the way he thinks about “the grid, structure, and geometry” of space, he says. “I really come at nature through abstraction. People call me a plein air painter, but I’m not really. Though I always work outside, I come in and work things out in the studio.” Berta Walker, who’s shown DuToit at her gallery for about 15 years, calls him an “expressionistic impressionist.”

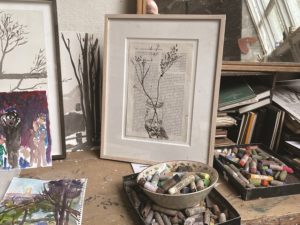

When you step into the studio, the first half is occupied by DuToit’s framing business. This leads into his art studio proper — a tall, vaulted space with north-facing windows that allow him to work under natural light alone. “It’s amazing! It’s never dark in here,” he says.

DuToit has made other changes in addition to the walls. It looks quite different from the funky, modular space seen in photographs of Bultman’s wife, Jeanne, tending the garden out front. The flying buttresses that supported the main studio are gone; the leaky roof has been replaced with a flat rubber one; and the pitched windows have all been replaced, though leaks remain an issue. “It’s not so thought-out for wet Cape Cod conditions,” says DuToit.

Over the years, DuToit has turned it into an adaptable space, with a basic bed, refrigerator, and kitchen sink. There’s a narrow loft where Nanno de Groot slept when he rented the space in 1956. (He also purportedly suspended a trapeze from the ceiling.) These days, DuToit uses the loft for storage.

DuToit’s daily routine is loosely structured. “I try to meditate for about half an hour and settle into my morning,” he says. “Then, I see what speaks to me, what I want to work on.” On one table is a still life of flowers that DuToit has rendered in a series of pastel and charcoal drawings.

DuToit’s framing business takes up most of the high season. “I do a little drawing when I can, but I don’t try to paint in the summer,” he says. It’s too much with his teaching commitments at Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill. “I paint through the whole winter, pretty much every day.” Sometimes he paints in his parked car for 40-minute bursts before the winter cold drives him inside.

“I often work on a lot of things at the same time,” he says. “I don’t get too focused on one thing. I can always put it away to start something else. Usually, I try to get a bunch of pictures started when there’s warmer weather outside. I also work from memory and imagination.”

After more than 30 years, DuToit’s space is starting to get cluttered with panels, canvases, and frames stacked layers deep. His solution: “I’ll just start painting over paintings after a certain point.”