WELLFLEET — For years, ecologist and beekeeper John Portnoy has sold up to three varieties of honey at the Wellfleet Farmers Market — each made from the nectar of seasonal blooms, first black locust, then winterberry, and last, sweet pepperbush. But on a sunny Wednesday morning this month, his stand displayed only a couple of baskets of garlic and a carton of berries. The honey was missing — as it has been the entire summer.

bees

SELECTIVITY

The Quest for a Local Queen

For Outer Cape beekeepers, a chance to raise more resilient colonies

WELLFLEET — The bee yard bakes in the midday sun, redolent of honey and the faint spice of propolis. Workers dart from hive entrances, returning heavy with pollen and nectar to feed burgeoning masses of larvae. We remove the hive cover and set a small open wooden cage atop the frames. A freshly hatched queen crawls out, cautious. Nurse bees sniff her curiously before she disappears down between the frames, seeking out the pheromone of the old queen. The two will battle; the strongest survives.

The practice of selectively raising honey bees on the Outer Cape has a small but growing following. Until recently, local beekeepers would typically order bees from apiaries in Georgia and other Southern states, receive a package in the spring, and set up their hives. Come winter, many of these colonies would weaken and die, so beekeepers were forced to buy another round of bees from Georgia the following spring.

John Portnoy started keeping bees in Wellfleet in the late 1980s. I’m his son, and I grew up watching the process and learning a little. Following him into his apiary again over the past few months, I discovered that the practice of local beekeeping is evolving. After years of frustration with winter losses, John is trying to raise bees adapted to colder climates.

Most commercially available bees trace their lineage to Italy, so a first step was to special-order queens from Russian and Eastern European stock. With these queens as a first generation, John began learning bee husbandry, aiming to create a strain adapted to our local environment. His efforts paid off, and now he supplies local beekeepers with their queens.

So how do you create a local queen? “You have to have a strong colony to begin with,” John says. In early summer, when the hive is flourishing, overcrowded bees prepare to swarm — which is a good thing in the sense that it’s an indicator the colony has grown and thrived. The swarm will divide one colony into two. But before that can happen, the bees must raise a new queen, several, in fact, of whom only one will succeed.

When rearing queens, you have to mimic those swarm conditions, timing the work with a strong nectar flow and filling a “queen nursery” with pollen stores and plenty of nectar. Adding frames of brood will attract nurse bees, needed to tend to the new queens-to-be. But the old queen must be excluded. She would kill the growing queens if she found them in her colony.

Once the nursery is prepared, John selects larvae from the strongest genetic line and gingerly places them into tiny plastic cups. The cups face downwards in the hive, mimicking the orientation of natural swarm cells, constructions of comb where a healthy colony would rear its new queen candidates. This type of cell tells nurse bees to keep feeding the larvae royal jelly — the special food that sets off the epigenetic process by which a generic female larva grows into a queen.

After four or five days, the queen cells are capped by the nurse bees, and the larvae begin their metamorphosis. Before they hatch, the new queens must be separated, for the first to emerge will systematically eliminate the other queens in the chamber. Once hatched, the new queens can then be introduced into other hives.

The advantages of locally adapted honey bees are well documented, most extensively in Europe, where honey bees are native, with many local subspecies. A series of studies by an international nonprofit group called Prevention of Honey Bee Colony Losses (COLOSS), launched throughout Europe in 2009, found that locally bred bees survived 15 percent longer than bees brought in from other areas.

Truro beekeeper Daniel Smith, who raises queens in Truro, points out that raising a local population is bound to mean healthier bees. “By using local queens, you are not introducing your colonies and those of other beekeepers to diseases from other areas,” he explained.

The most common reason for colony loss — both in Europe and here in the U.S. — is the Varroa mite, which is a vector for many diseases. The mites themselves are about the size of a pinhead, which, sized up to human proportions, would be like having a parasite the size of a frisbee attached to your stomach. The COLOSS studies indicate that local bees are better adapted to survive infestation and to fight off divergent virus strains.

There are myriad other advantages to selectively raising bees. A fundamental one is this: in general, Southern queens lay eggs year-round, whereas Northern bees stop raising brood in the cold months, conserving their resources to survive the winter as a smaller cluster.

Raising a local strain of bees also offers the opportunity to select for traits like gentleness and honey yield. In addition, locally bred queens are primed for better reproductive success than those shipped from the South, whose sexual development is interrupted by the whole business of shipping.

Introducing a locally raised and unmated queen to a hive does carry a risk. When she flies out to mate, there’s always a chance she could get snapped up by a bird or other predator and not return to the hive. Another issue beekeepers worry about while their young queens are off in the wild is who she ends up mating with. If other beekeepers nearby are sticking to the old formula and raising bees imported from the South, she might mate with one of their drones. If so, the new colony’s brood will have only half of the DNA of a locally adapted bee.

The more beekeepers use locally adapted queens, the stronger the local gene pool will be. Wellfleet beekeeper Barbara Brennessel had trouble with Southern-bred queens in her first two years of beekeeping, but “a locally raised queen came through and in our third year we had a good honey harvest, and several after that.”

Selectively raising local bees is not as simple as mail-ordering a package of bees and dumping them in a box. But with the failure rate of imported queens estimated at close to 50 percent, there is increasing motivation to try something different. If the local beekeeping community commits to learning, and demand for local queens grows, the Outer Cape could be on its way to a hardier local honey bee.

Pirates and Pollinators

Fran Raleigh teaches a Zoom course on “Birds, Bees, Butterflies, and Pollinators” as part of Coastal Connections on Tuesday, March 23rd, at 1 p.m. Call the Orleans Senior Center at 508-255-6333 to register. There is also a course on “Maritime Ghosts and Seafaring Spirits,” with Roxie Zwicker, on Wednesday, March 24th, at 1 p.m. To register, call the Sandwich Council on Aging at 508-888-4737.

VIEW FROM THE HIVE

Late Summer Jobs for Field Bees

Carrying water in a dearth, then making white wax for the new nectar flow

Most people know that honey bees collect nectar and pollen from flowers. But field work for honey bees is much more diverse than that.

Field bees suck nectar from the base of flower petals into their crops, or “honey stomachs,” anatomically arranged like the more familiar pre-stomach crop of a chicken. They often fly back to the hive with a full load of nectar nearly equal to their body weight. Pollen, on the other hand, is gathered externally, packed into hairy pollen baskets (corbiculae) on the bees’ hind legs. A colony must gather hundreds of pounds of nectar, for energy, and tens of pounds of pollen, for fat and protein, to sustain itself each year.

One might think that such massive nectar and pollen collection would keep a colony of little insects fully employed, but then one would be wrong. Colony maintenance requires two more essential materials from the environment: tree resins and water.

Field bees collect tree resin and carry it, like pollen, on their hind legs. Back at the hive, workers work the sticky sap into propolis, a coating for hive walls and to chink crevices and gaps against drafts. Propolis has strong antiseptic properties, recognized by the ancients as an effective human wound dressing (along with honey), and now by modern entomologists as an important component of the honey bee colony’s immune system. With the Cape’s extensive pitch pine forests, tree resin is plentiful. Though gummy propolis sticks to the fingers, it has a wonderful fragrance.

Water has two primary uses: to dilute stored honey and to prevent literal meltdown of wax honeycomb during hot weather. Bees can eat nectar directly, but for long-term storage (think winter) bees must reduce the water content of nectar to less than 18 percent to prevent fermentation. (Mead may be a rare treat for humans, but it gives wintering bees the runs.)

The bees evaporate excess water from the nectar by drawing it up and down their tongues (proboscises) and by fanning across the surface of the honeycomb.

When nectar is in short supply, the bees turn to their honey stores for energy, and to do that they have to rehydrate it with water from the outdoors. That’s why observant bee watchers, seeing them gather at pond shorelines, birdbaths, and swimming pools, know that the bees are experiencing a nectar dearth.

Otherwise, the bees collect water to promote evaporative cooling of the hive. If the temperature of the hive interior rises much above the mid-90s, the wax comb begins to weaken, sag, and can collapse. To counter this, worker bees smear collected water over comb surfaces and fan their wings in a concerted fashion to promote its evaporation. Thus, the whole hive interior “sweats” to stay cool.

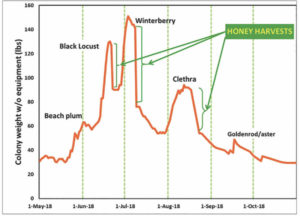

Nectar flows — times when important honey plants are in bloom — are fairly predictable but very limited in duration on the Outer Cape. In total, they amount to only six to eight weeks through spring and summer. About 20 years of scale-hive monitoring in north Wellfleet, recording hive weights every day during the warm months at dusk, show that colonies have daily gains only during the flowering of beach plum, black locust, winterberry holly, and sweet pepperbush (Clethra). In some years there’s a minor bump from fall goldenrods and asters. Otherwise, food gathering is strictly hand-to-mouth, and colony weight is either stable or falling.

A nectar flow puts bees and their keepers in a good mood. It seems to completely preoccupy the bees, so beekeepers can work strong, populous colonies with little fear of being stung. And one of the most gratifying sights for the beekeeper is to pop open a hive cover during a major nectar flow and experience the joy of “white wax.”

When it is first secreted from the undersides of the abdomens of young workers, beeswax is pure white and a sure sign of an abundant supply of incoming nectar. They’re building comb to make storage space for the nectar that’s flowing now. Look around the woods this week and you’ll see the source — fragrant sweet pepperbush surrounding the Outer Cape’s kettle ponds.

VIEW FROM THE HIVE

Swarming Is a Sign of Success

When honey bees take to the woods, they’re driven by a collective purpose

A honey bee colony’s plans and those of its beekeeper often diverge, and those disparate intentions of bee and keeper can confuse and confound the objectives of both. At no time during the year is this more evident than in June, when a strong overwintered colony of honey bees is focused on one thing — reproduction.

For social insects like honey bees, passing on one’s genes is less about making more bees per se, and more about reproducing the colony. Individual social bees, even queen bees, can’t survive alone and require support from the whole hive — the superorganism. In this way, the proliferation of bees in a colony might be likened to cellular division, with groups of cells (bees) specializing, like organs in our own bodies, to collaborate, communicate, and sustain the whole organism, in this case, the colony. To truly reproduce and spread across available habitat, the honey bee colony must swarm, that is, split off a daughter colony early enough so that it has time to grow and accumulate enough honey and pollen for the upcoming winter.

Since mid-April, the few thousand “winter bees,” which have made it through the cold months and now work themselves to death in the field, have been joined by a rapidly growing work force of newly minted summer bees. Fueled by the sequential nectar and pollen flows from blooming willow, maple, beach plum, and black locust, a colony’s population typically reaches 30,000 worker bees in May, and will achieve an annual population peak of double that number by the end of this month.

From the perspective of species survival, a populous honey bee colony swarms to pass on its genes, but the actual process that motivates the colony to swarm is complicated. During spring’s explosive population growth, the “brood nest,” where the queen lays eggs and emits colony-controlling pheromones, and where new bees are reared, becomes crowded. Fanning workers have more trouble ventilating the brood nest. With congestion and poor ventilation, individual workers receive less queen pheromone, the essential signal for colony stability. This is even more likely if the queen is aging and producing less pheromones.

Swarming becomes an irrevocable decision, reached by consensus of the colony, when the aging queen is guided by nurse bees to lay eggs in specialized cells, called “queen cells,” which they build along the bottom edges of wax comb. The eggs she lays there are no different genetically from their thousands of sister eggs destined to become workers. But they are fed royal jelly, enriched in fats, proteins, and sugars, once they hatch. This richer diet changes everything: turning on genes that would remain dormant in workers. These awakened genes profoundly redirect development to produce not short-lived sterile workers but reproductively active female bees that may survive in the hive for years.

Once queen cells are capped and the larvae inside reach the resting pupa stage, a swarm will emerge, always accompanied by the old queen, but definitely not led by her. One of the bees growing in the hive’s queen cells that are left behind will soon enough begin laying to rebuild the colony the swarm has left behind. But that’s another story.

Swarms happen most often during the middle of a sunny and warm June day and often right after clearing weather. The swarm usually bivouacs temporarily in a nearby tree, commonly in plain view and at sufficient height to frustrate the beekeeper, while it sends forth scouts to find a more permanent home.

Because the swarm removes perhaps 60 percent of the workforce along with quite a bit of harvestable honey from the beekeeper’s domain (and may cause problems for neighboring humans if the bees take up residence in an attic or shed), swarms are traditionally dreaded by some beekeepers. But swarms can be looked-out for and prevented by beekeepers who make “splits,” where beekeepers set up the emerging queen cells in new hives. Either way, whether managed or lost to the woods, a swarm is a good thing. It’s a sign of reproductive success for the parent colony of bees.

VIEW FROM THE HIVE

Sweet Pepperbush Honey Harvest

The last big nectar flow of the year is happening now

WELLFLEET — In early August, sweet pepperbush, also called summersweet (Clethra alnifolia), comes into bloom where I live, in north Wellfleet. And when it does, the “honey factory” goes into full production.

The bee yard is one loud hum as thousands of bees per minute pour in and out of hive entrances. Foragers streak off to swampy lands and kettle pond shorelines where clethra’s white spikes and penetrating perfume attract insects like a gravitational field. Bees return to cram thorax-to-thorax through narrow hive openings, their abdomens distended with sweet nectar. The chaos continues from just after dawn until dark.

During humid nights, the fragrance of nectar wafts throughout the yard as thousands of hive-bound bees fan the day’s nectar yield — that’s how bees reduce its water content to prevent fermentation. Honey is the result, and the bees’ winter survival depends on it.

Beekeepers learn to anticipate these intense “nectar flow” events. They are discrete and short-lived on the Outer Cape, totaling only five or six weeks per year. The bees must make the most of them or starve while they are clustered against the cold in their hives during our six month–long winter.

Their keepers, too, are dependent on the nectar flows, hoping for good bee flight weather during each one. Cold or wet weather will keep foragers at home and can put a serious dent in the bees’ winter food, and in our hopes for a harvestable excess of honey.

Since 2001, Wellfleet’s major nectar flows have been measured using scale hives, that is, beehives set on platform scales. Tracking these colonies’ daily weight gain throughout the warm months, I’ve seen some colonies bring in nearly 20 pounds of nectar in a single day.

Scale-hive monitoring in our apiary has shown that just four major plant blooms contribute most of the nectar our local bees gather. The first occurs in April with nectar from willows (Salix spp.) and red maple (Acer rubrum). We humans shouldn’t take honey made from it, because the bees need it to build strong colonies as the small overwintered population of bees surges. These blooms bring pollen, too, by the way, which is crucial to the bees’ growth — it is their source of protein.

Next to bloom is beach plum (Prunus maritima), in early May, and black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), later in the month. Their flowers are promising, but May is often a wet, stormy month out here in the North Atlantic, so bee flight and foraging is often limited while they’re in bloom.

After locust comes winterberry (Ilex verticilata), a native holly that blooms around wetland edges in June, and almost always yields an abundant crop of light-colored and aromatic honey.

The stretch between the June winterberry and this last major nectar flow, with the clethra that is in bloom now, is a long one. You might see bees idly hanging out during that dearth, “bearding” in the cool air outside their hives.

The sweet pepperbush will be our bees’ last hurrah, nectar-wise. The Outer Cape has few open fields for fall flowers like goldenrod and asters. Our remaining undeveloped uplands are covered with oaks and pines, which don’t produce nectar.

Without our native wetland shrubs, winterberry and sweet pepperbush, honey bees probably wouldn’t overwinter here without beekeeper subsidies of sugar syrup.

At this time of year, the beekeeper’s work revolves mostly around the harvest. In early summer, we added boxes of frames for the bees to build comb in and store extra honey. Now we take them off full, the medium-sized ones I use weighing about 50 pounds each. We scrape the wax cappings off the comb, spin out the honey in an extractor, and put it in jars. We make sure to leave plenty of honey with the bees — at least another 50 pounds per colony — to get them through winter.

Although our bees need them, it is worth noting that these native plants don’t really need our bees. That’s why I’m circumspect about the currently popular idea that keeping honey bees somehow benefits the local native ecosystem. The truth is, that’s probably not the case here.

Honey bees are not native to North America; they were introduced with European settlement in the 17th and 18th centuries. The native ecosystems of Cape Cod did fine for thousands of years, and would continue to do so, without European honey bees because we still seem to have a diverse assemblage of native pollinators. This is despite occasionally high insecticide use in the last century and the introduction of “new” (to a bee) parasites and diseases.

But that’s not to say that honey beekeeping can’t promote native biodiversity elsewhere. Honey bees’ big value on this continent is in relation to modern intensive agriculture under way in parts of the country where growing consists mostly of huge single-crop, weed-free monocultures, like citrus in Florida, grains and soy in the Midwest, or almonds in California.

Here, bees can help make your garden and raspberry bed bountiful. My neighbors tell me their blueberry crop has been greatly enhanced by our honey bees. But mostly, local beekeepers’ coexistence with plants amounts to protecting the plants that give us our nectar flow.

Without them, it would be a hard life for honey bees and beekeeping in this oak-pine forest.

John Portnoy is an ecologist whose career with the Cape Cod National Seashore focused on the study of our local salt marsh ecosystems. He has been goofing with the bees for 30 years.