Most people know that honey bees collect nectar and pollen from flowers. But field work for honey bees is much more diverse than that.

Field bees suck nectar from the base of flower petals into their crops, or “honey stomachs,” anatomically arranged like the more familiar pre-stomach crop of a chicken. They often fly back to the hive with a full load of nectar nearly equal to their body weight. Pollen, on the other hand, is gathered externally, packed into hairy pollen baskets (corbiculae) on the bees’ hind legs. A colony must gather hundreds of pounds of nectar, for energy, and tens of pounds of pollen, for fat and protein, to sustain itself each year.

One might think that such massive nectar and pollen collection would keep a colony of little insects fully employed, but then one would be wrong. Colony maintenance requires two more essential materials from the environment: tree resins and water.

Field bees collect tree resin and carry it, like pollen, on their hind legs. Back at the hive, workers work the sticky sap into propolis, a coating for hive walls and to chink crevices and gaps against drafts. Propolis has strong antiseptic properties, recognized by the ancients as an effective human wound dressing (along with honey), and now by modern entomologists as an important component of the honey bee colony’s immune system. With the Cape’s extensive pitch pine forests, tree resin is plentiful. Though gummy propolis sticks to the fingers, it has a wonderful fragrance.

Water has two primary uses: to dilute stored honey and to prevent literal meltdown of wax honeycomb during hot weather. Bees can eat nectar directly, but for long-term storage (think winter) bees must reduce the water content of nectar to less than 18 percent to prevent fermentation. (Mead may be a rare treat for humans, but it gives wintering bees the runs.)

The bees evaporate excess water from the nectar by drawing it up and down their tongues (proboscises) and by fanning across the surface of the honeycomb.

When nectar is in short supply, the bees turn to their honey stores for energy, and to do that they have to rehydrate it with water from the outdoors. That’s why observant bee watchers, seeing them gather at pond shorelines, birdbaths, and swimming pools, know that the bees are experiencing a nectar dearth.

Otherwise, the bees collect water to promote evaporative cooling of the hive. If the temperature of the hive interior rises much above the mid-90s, the wax comb begins to weaken, sag, and can collapse. To counter this, worker bees smear collected water over comb surfaces and fan their wings in a concerted fashion to promote its evaporation. Thus, the whole hive interior “sweats” to stay cool.

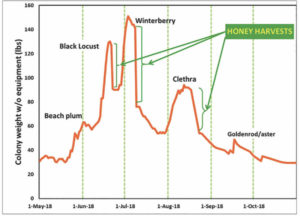

Nectar flows — times when important honey plants are in bloom — are fairly predictable but very limited in duration on the Outer Cape. In total, they amount to only six to eight weeks through spring and summer. About 20 years of scale-hive monitoring in north Wellfleet, recording hive weights every day during the warm months at dusk, show that colonies have daily gains only during the flowering of beach plum, black locust, winterberry holly, and sweet pepperbush (Clethra). In some years there’s a minor bump from fall goldenrods and asters. Otherwise, food gathering is strictly hand-to-mouth, and colony weight is either stable or falling.

A nectar flow puts bees and their keepers in a good mood. It seems to completely preoccupy the bees, so beekeepers can work strong, populous colonies with little fear of being stung. And one of the most gratifying sights for the beekeeper is to pop open a hive cover during a major nectar flow and experience the joy of “white wax.”

When it is first secreted from the undersides of the abdomens of young workers, beeswax is pure white and a sure sign of an abundant supply of incoming nectar. They’re building comb to make storage space for the nectar that’s flowing now. Look around the woods this week and you’ll see the source — fragrant sweet pepperbush surrounding the Outer Cape’s kettle ponds.