Probably the most common image that comes to mind when someone mentions honey bees are those tidy (classically white) wooden hive boxes set out in a field, orchard, or country garden. But why bees in boxes? People have been eating honey and even tending bee colonies for thousands of years, well before sawmills. And colony-forming honey bees have been around for many millions of years, inhabiting and evolving in nature, where rectilinear construction is completely absent.

Before the Age of Boxes, honey bees made their homes mostly in hollow trees, and still do: just a few years ago, there was a large colony doing just fine in a massive catalpa tree trunk in Wellfleet center. Unfortunately for the bees, their energetic summer foraging and heavy flight activity was a little much for nearby human residents and they (the insects) had to be removed — to a box, of course.

“Primitive” people, apparently lacking boxes, collected honey and succulent bee larvae from wild bee colonies in forest trees. Beelining, an ingenious method for finding bee nests using captured and temporarily enslaved bees, and which you can no doubt Google, was quite a sport through the last century.

So, again, why boxes? The big breakthrough in honey harvesting, from the adventurous search, discovery, and pillage of wild bee colonies to more staid bee culture in apiaries, pretty much paralleled the general transition of human societies from hunter-gatherers to farmers starting about 10,000 years ago. It was easier (though perhaps less fun) to give the bees a home so that they could be reliably found and “farmed,” meaning protected from predators, propagated, and periodically robbed of some honey.

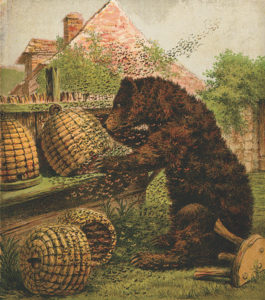

Lots of artificial bee homes have been tried over the last few hundred years, from bee “gums” (chunks of hollow trees), to straw skeps, to the currently most-popular wooden box. The popularity of the last-named hinges on its acceptance of wooden frames, on which the bees build their honeycomb, and which can be easily removed by the beekeeper for colony inspection and honey harvesting without destroying the insects’ colony or even the honeycomb.

Meanwhile, it’s well past the winter solstice and Cape honey bees, though still rarely leaving home and dependent on food collected last year, have begun rearing new workers to replace the dying “winter bees” that carried the colony through the dark months. Watch this month for foraging honey bees on any of the earliest blooming spring flowers like crocus, heath, hazel, and willow, on those (increasingly common!) March days when the sun shines and air temperature pushes 50 degrees.