I was looking at an iris the other day, watching a bee tumble and bumble its way through the folds, ripples, and petals, drunk with pollen-dusted happiness, and I thought: “That’s me.” That bee embodies exactly the joy I feel about these marvelously flamboyant flowers.

I’ve had a thing for irises, particularly bearded irises, ever since I was a kid in Texas where my neighbor had a yard full of them. I love the expansive color range of these stately plants, going from peerless white to jet black (I think among the blackest of any flower). In between, they span much of the spectrum except for true green or scarlet. Their name comes from Iris, the Greek goddess of the rainbow who was a messenger between the gods and humanity, running missives back and forth on her colorful bow.

I have tried growing these perennials in every place I’ve gardened — in most of them, with limited success. Some spots were too shady; in others, the soil was too heavy. But on the Cape, I have found iris heaven.

The bearded iris (Iris x germanica) — the “beard” refers to the fuzzy bee strip on its petals — is thought to be a naturally occurring hybrid of central and southern European native irises. Over the centuries, thousands of varieties have been bred.

Considering the wealth of color choices that have been developed, how would I decide on a color palette that has anything resembling a point of view? I was immediately drawn to the off shades: dusty in-between colors like fawn, rust, mahogany, olive, mauve, puce, oyster, and, of course, the blackest ones I can find. You can tell by the color names that these are not primary colors but the kind of blended colors an artist would create.

I fell in love with these moody shades several years ago when I discovered the paintings of Sir Cedric Morris (1889-1982), who bred and painted irises at his Suffolk, England house, Benton End. Along with his life partner of 60 years, painter Arthur Lett-Haines (1894-1978), he also ran an art school there and taught the young Lucien Freud and other students how to paint plein-air in the garden.

Morris doted on misty, subtle tints, especially the buffs, grays, and browns that drive me crazy. In the U.K., some of his extant hybrids have become chic collectors’ items (all with the name Benton in their titles). He favored plicatas as well, which feature stippling, lines, or shading on their edges. I have yet to find a mail-order source in the U.S., and, trust me, I’ve scoured the internet. This unavailability only makes me want them more.

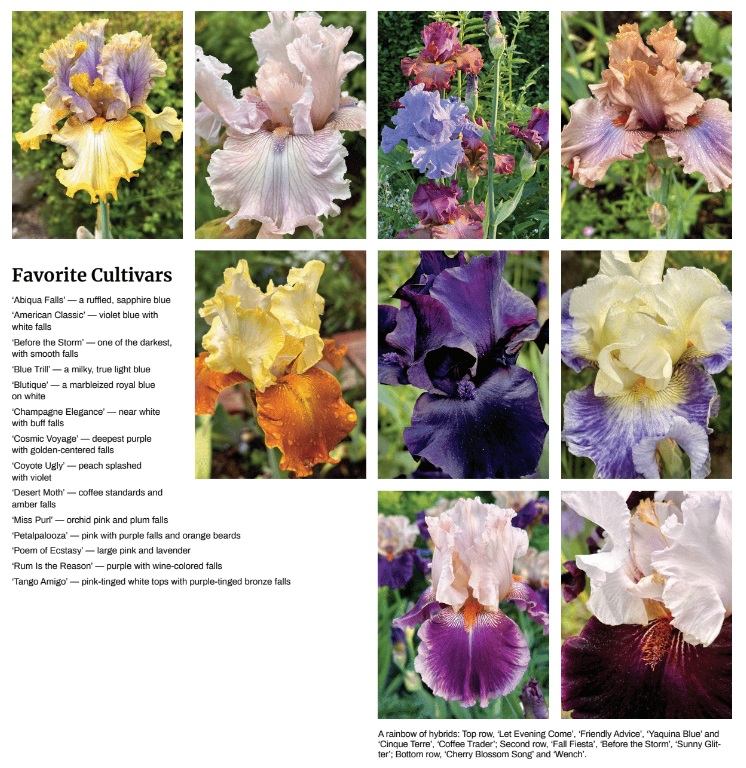

Not one to be thwarted, I’ve tried to gather as many off colors as I can from specialist online American sources such as Schreiner’s Iris Gardens and Cascadia Iris Gardens. Some of my favorites include ‘Coffee Trader’, khaki with sapphire centers; ‘Friendly Advice’, a silvery ecru; and the oddly named ‘Wench’, soft peach with deep eggplant falls (the part of the flower that drops downward).

When friends visit, I encourage them to smell the different iris blooms to see if my theory that the scents match their colors holds up. Invariably it does. Browns smell like root beer. Yellows like lemons. Purples like grape, specifically grape candy or gum. Others smell like divinity fudge or have a perfume that is indescribably powdery. White doesn’t really smell like coconut — although maybe it would to the easily suggestible. Comparing scents among the different iris plants is truly a transporting activity — one that eight-year-old me enjoyed back on those hot Texas mornings.

Given the right conditions, irises are tough and low-maintenance. They don’t mind being transplanted; in fact, they need it once in a while. A midsummer division of larger clumps of rhizomes every five or so years will yield more flowers and stronger leaf growth. Midsummer is the time to plant new rhizomes.

I’ve discovered that iris placement makes all the difference. In our climate, where it’s not too hot, make sure to place the rhizomes so they are partially exposed to the sun, orienting the fan of leaves so the root faces the light for most of the day. They love free-draining sandy soil, and our Outer Cape conditions help prevent root rot over the winter. Irises work well planted along a wall or fence on their own, or if you want to feature them in a flower border, plant them at the very front with some space around their roots.

They like to be the star, not crowded or shaded by other plants. There is a marked difference between my ‘Beverly Sills’, which has quadrupled in size in a gravel garden setting where she has no one around her, and my ‘Edith Wolford’, who has spent the last two summers subsumed by a giant catmint too near a sprinkler. In her third year, Edith has let me know by sulking and going on a bloom strike that she would like to be moved. I will oblige her after her few flowers fade. Patience, Edith.

Irises have a limited bloom time — just a few weeks — but what a grand impression they make in such a short period. For the rest of the growing season, their glaucous sword-shaped leaves make useful vertical accents in the garden. With their large heads and spindly bodies, staking is often required.

They’re loud and brash and maybe even a little too much. “Well, hello! Where’s the party?” my friend said the other day when I showed him some head shots from my collection. If they bloomed all summer, then we might not appreciate their fleeting gloriousness as much.

As the old showbiz saying goes, “Always leave ’em wanting more.” That’s what the irises do as I head out to dig another bed for this summer’s iris delivery.