“An overarching thesis of mine is that stodgy old P’town takes itself a bit too seriously and that the people who live there have gotten rather boring,” writes Sue Edge, the founder of Beach Trash, via email. Beach Trash is a Provincetown-based humor and gossip zine. The name Sue Edge, a pun on “sewage,” is an alias. “I hope to jolt people out of their routines with something new,” Edge explains.

Zines are self-published booklets created by one person or a small group of people. They often include countercultural commentary, philosophical observations, or original art.

They originated in the 1930s among science fiction lovers. Zine is short for “fanzine,” which is itself short for “fan magazine.” Pre-internet, zines allowed fans to network, share ideas, and collaborate.

Today, zines are still usually low-budget productions, printed on copy machines. In cities, they are found in independent bookstores or record stores near college campuses. On Cape Cod, they’re harder to track down. But they’re here if you know where to look.

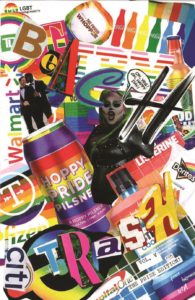

Beach Trash was started in March 2021 as a creative outlet during Covid. “Provincetown is my home, and also a place where I have felt trapped and isolated,” says Edge. “These dual feelings of love and hate helped inspire me to create a satirical zine that celebrates insanity, chaos, and queerness.”

Inside Beach Trash’s colorful collage wrapping is news from Gossip Squirrel (“Did you hear? A salmon was spotted during Bear Week”); restaurant reviews by Roger Bleepert (who awards four stars for the consistent use of the word “clamps” for “clams”); and a recipe for Beach Trash (ingredients include queer lunacy, whimsy, and a can of baked beans, preferably Bush’s).

The initial response from the community was “confusion and bewilderment, which is exactly what I was going for,” Edge says.

Beach Trash has several contributors, says Edge. Since the contents are entirely anonymous, it’s not possible to know whether that’s true. The seven issues published to date aren’t sold in stores but can be found around town at no cost. Some issues include a QR code for donations.

“Good places to look are small lending libraries, coffee shops, and bulletin boards,” says Edge. “Often, you’ll find one somewhere you don’t expect.” Superfans can email Edge: “If they ask nicely and live close by, a copy might appear in their mailbox.”

East Sandwich-based artist Nick Zaremba has a different perspective on zines. He started making them in 1994 as a freshman in high school. They were popular among the creative juniors and seniors he looked up to, many of whom expressed themselves through music, skateboarding, and graffiti art.

Zaremba fell in love with the idea of a pocket-sized magazine that was “all me,” he says. “I had artistic control over everything.” Since his early start, Zaremba has made 45 zines, which he sells online, at book fairs, and in stores in Boston, New York, Los Angeles, and Kyoto, Japan.

One, called Human Behavior at Work, is a collection of drawings, photos, paintings, collage, and found text made in 2020. On one page, a figure floating up from a sea of hair says, “We all have some areas of vulnerability. Not everything in life can be understood or resolved.” The 32-page booklet was made by hand, scanned to a computer, and printed in grayscale on white cardstock.

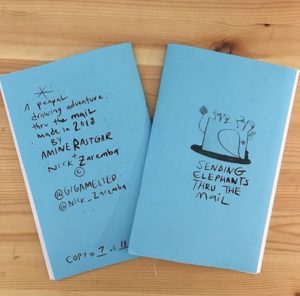

Another zine, Sending Elephants Thru the Mail, is a collaborative collection of drawings on vintage paper. Zaremba says it was a way to stay in touch with a friend who moved away.

In 2006, Zaremba started XXVI Press with his brother Matthew. One of their services is producing and selling zines for other people.

Graphic designer Chris Kelly, who is co-owner of Longstreet Gallery in Eastham (and does design and production for the Independent), started making zines about five years ago. He sells them at the gallery and on his website. Kelly’s work often has him solving other people’s problems. But in that daily grind, creative ideas surface that he stores for later.

While Kelly wouldn’t describe himself as a photographer, his zines feature photographs and contributions by local artists. “They’re a repository of images and ideas,” he says. There’s no specific message he’s trying to get across. His three most recent — High Low, Myth, and Pilgrim — are about his travels around and beyond Cape Cod.

A spread in Myth has a shot of people eating lunch at Truro’s Terra Luna, with a poem about summer’s comings and goings: “The season is fleeting/ End of summer will come/ No siren songs beating/ Folks go back where they are from.”

Kelly says that people interact with zines differently than they do with other art. Their reactions are immediate, and they can rifle through a book’s pages in a way they can’t with a painting. Furthermore, you never know who will get their hands on one, or where they will end up.

A zine is a way, Kelly says, “to let someone into a world or viewpoint they might not know about or be interested in. They’re just a lot of fun.”