Duplicating a painting that vanished in 1990 might sound challenging. But Provincetown painter John Clayton, who is creating reproductions for Art Thief, a film by artist and gallery owner Arthur Egeli, says artists don’t necessarily need to come face to face with originals to create good replicas of them.

When recreating a painting, Clayton says, it’s essential to take a step back and discover what makes a piece memorable to viewers who aren’t studying every brushstroke. What matters is capturing the feeling a work of art inspires.

Three of Clayton’s reproductions will appear in Egeli’s film, which is currently being shot on the Cape. It imagines the motives behind the infamous Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist, when two thieves, disguised as Boston police officers, talked their way into the building and walked out with 13 works, including paintings and drawings by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Manet, Flinck, and Degas.

Inspiration for the film came in 2018, when Egeli’s wife, Heather, heard an episode about the still-unsolved theft on WBUR’s true-crime broadcast “Last Seen.” It was odd, she thought, that the story did not delve into what the motives for the robbery might have been. After all, the heist made news around the globe and the stolen works could never be sold in any market.

In Art Thief, fictional thieves Kevin Deeley and Bobby “the Rat,” played by Max Deacon and Chris Lazzaro respectively, are motivated by the desire to possess beautiful art.

Clayton’s replicas of Van Gogh’s Irises and Starry Night hang on display in a room made up to look like the Gardner Museum at the Cultural Center of Cape Cod in South Yarmouth. Clayton painted these before the film project began, and Egeli, who knows the painter’s impressionist style well — Clayton is represented at the Egeli Gallery in Provincetown — bought them for the set.

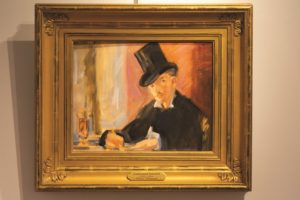

Egeli also commissioned a replica of Édouard Manet’s Chez Tortoni by Clayton. The original used to hang in the Gardner Museum’s “Blue Room” under a portrait of the artist’s mother. It was the only masterpiece stolen from the museum’s first floor.

Chez Tortoni depicts a top-hatted man seated next to a foggy window in a Parisian café, halfway through a beer, and writing something — a letter, Clayton imagines. Though the original measures only 10 by 13 inches, the inquisitive, caught-off-guard expression of the subject has lifelike magnitude. Bent forward over the letter, he looks up with wide eyes and slightly raised eyebrows, as if to ask the viewer why she walked up to his table.

Clayton says it is not unusual for artists to paint replicas. “There are two reasons to copy a painting,” he says. “One is to learn something from the original.” Copying the brushstrokes, palette, and figuration of a master painter, he says, helps artists learn technique.

The other reason, he says, is financial. Some people want to display a copy of a classic without spending a fortune. Clayton says he once reproduced a Cezanne for this reason.

As a young man living in Los Angeles, Egeli says, he often painted replicas for people who wanted to let others think they owned originals. Fakes were a regular source of income for artists there because reproductions stand in for originals on movie sets.

The rights to use a painting — even a replica — can be expensive. That’s why Egeli says he elected to fill background display space with many of his own paintings.

Clayton’s usual work is impressionistic. He is a colorist, he says, and for these commissions he enjoyed matching Van Gogh’s and Manet’s expressive palettes. “Van Gogh weaves one color into another with these fiery brushstrokes,” Clayton says.

Before he started putting brush to canvas for the Manet replica, Clayton tried to research what colors the artist had available to him. The colors in Chez Tortoni are more muted than any Clayton uses in his own rosy Provincetown landscapes. But Clayton didn’t find a lot of technical information on Manet’s palette. In the end, he relied on his own eyes and color knowledge to match the muted gray-blues and mauves surrounding the subject.

Clayton noticed that, all throughout, there were warm undertones. He prepared his linen canvas with a wash of burnt sienna, thinned with turpentine. Then he divided the canvas into 10 rectangles on which he spent hours sketching the scene in pencil.

Once the sketch was finished, he colored it in with a wash of base colors — black for the top hat and a peachier skin tone for the face. Slowly, he built detail on top of each element. The work, he says, came at a perfect time, keeping him purposefully occupied during the height of the pandemic.

Not every piece needed for the film was done by Clayton. Painter Steve Toomey, who splits his time between Worcester and Provincetown, painted a replica of Rembrandt’s only seascape: Christ in a Storm on the Sea of Galilee. His detailed still lifes and scenes of familiar Provincetown sites, such as the interior of Sal’s restaurant, where he used to work, translated readily to Rembrandt’s style.

Admiring Toomey’s work, Clayton says he doesn’t think he has the attention span to reproduce a Rembrandt. He’d rather comb through figurative representations in an impressionist painting, finding the “simplest patterns.”

If you squint at Chez Tortoni, he says, “You only see the dark of his hat, the darker coat, and the dark of the background. Everything else is in the light.”