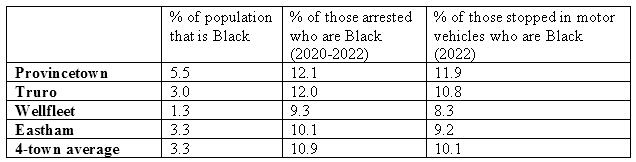

Black people on the Outer Cape are about 3.3 times as likely to be arrested as the rest of the region’s population, according to police department data from Provincetown, Truro, Wellfleet, and Eastham and population data from the 2020 census.

From 2020 to 2022, between 9.3 and 12.1 percent of those arrested in the four towns were Black, while an average of 3.3 percent of the towns’ populations self-identify as African American/Black.

Little appears to have changed in the racial breakdown of arrests and traffic stops since the Independent reported on those numbers three years ago. In 2019, arrests of Black people across the four towns totaled between 8 and 12 percent.

Black motorists are stopped by police just over three times as often as they should be, given their proportion of the Outer Cape population.

What the Data Show

As was the case three years ago, local police chiefs argue that arrest and traffic stop proportions should not be compared to towns’ racial compositions. Most said that the influx of visitors, particularly in summer months, makes the year-round population data inaccurate.

“Provincetown is a unique community and destination,” Provincetown Police Chief Jim Golden wrote in an email. “Due to Provincetown’s uniqueness, it’s difficult to use our ‘year-round’ census population to make meaningful data comparisons.

“Once summer arrives, our community becomes much more diverse racially, by age, and many other demographic indicators,” Golden added.

But an analysis of Provincetown arrests between 2020 and 2022 shows the summer racial disparity was actually less than it was during the rest of the year. In June, July, and August, 11 percent of arrests were of Black people — just under the year-round average of 12.1 percent.

In June, Golden was criticized by residents after he defended Provincetown officers’ treatment of five teenagers of color who were playing basketball, after a false report of a gun. Three of the teens frisked were year-round Provincetown residents, and the other two spend summers here with their families. In the wake of that incident, Anthony Teixeira, one of the youths searched by officers, said that there had long been a pattern of cruisers stationed next to the East End basketball court where he and his friends regularly played.

In Wellfleet, Deputy Chief Kevin LaRocco said the traffic numbers had to do with repeat offenses and the summer population increase. “There is no ‘discrepancy’ between the town’s racial makeup as it relates to the number of motorists of color who are stopped,” he wrote in an email.

“With the huge increase in population during the summer months — of visitors, part-time residents, and part-time workers,” LaRocco wrote, “it’s very clear how the number of POC drivers who are stopped or arrested rises, on average, in relation to the year-round demographic of the town.”

But data for 2023 through July show that, so far this year, Black people accounted for the most disproportionate number of Wellfleet’s motor vehicle stops in January and February: 10.8 and 15 percent of traffic stops in those months. In June and July, 7.2 and 7.4 percent of traffic stops were of Black people.

How Information Is Classified

Parsing the data is hard without a standardized set of racial categories. Census data, which are self-reported, include categories for multiracial identities, for example. The four police departments do not. And while Provincetown, Eastham, and Wellfleet do not list “Hispanic” as a racial category — considering it an ethnicity, as the census does — Truro does include it as a racial classification.

There is no standardized procedure among the departments for collecting racial data. Eastham Police Chief Adam Bohannon said that officers have been required to record racial data internally using an “E-Citation system” since 2020. When someone is stopped for a motor vehicle violation, police record race by appearance.

“The officers input this data to the best of their ability,” Bohannon wrote. “[They] do not specifically ask the individuals for their race in an effort to avoid conflict.”

Wellfleet Police Chief Mike Hurley told the Independent in 2020 that race is usually specified on government IDs, so officers rarely record race by appearance.

Although police departments challenge the data, community members of color and leaders in the know did not doubt the threefold discrepancy in arrest and traffic statistics.

Community Reactions

Donna Walker, Provincetown’s director of diversity, equity, and inclusion, said the police data did not surprise her.

Similarly, Methodist Pastor Edgar Miranda, who is of Puerto Rican heritage, was “not at all” surprised by the racial disparities. He said when he drives on Route 6, if he sees a car pulled over, he generally turns to look. Based on his observations, he said, “There’s a disproportionate amount of Black and brown people that I see pulled over that’s not representative of where they fall into the general population.”

Walker said that the Barnstable County Human Rights Advisory Commission is one avenue of recourse for people who feel their civil rights have been violated. Leslie Domínguez-Santos, coordinator of the commission, said “when we look at our data, the predominant number of intakes that we’ve gotten are based on race” rather than other protected classes like gender, age, and sexual orientation. “In our community of color on Cape Cod, people do have stories of racial bias with the police,” she said.

Across Cape Cod, she added, “I can say with full confidence that police departments are aware of racial bias and disparities, and they’re working hard to address them.”

But in the meantime, Domínguez-Santos said, the discrepancy in arrests is “disheartening” but not surprising: “It’s certainly the way that the community of color is feeling,” she said.

“It’s a real problem that a lot of people want to deny,” said Miranda. “But we can’t deny our history. We can’t deny the statistics. We need to deal with it and not bury it.”