Leading the way to her living room, Ardis Markarian adjusts a visitor’s view of Provincetown. “You don’t have to be a writer or artist to live here,” she says. “You can just be a regular person like me. I have no claim to fame — I just love it here.”

Markarian is wearing a seafoam green Piggy’s shirt from the 1970s, black sandals, and cut jeans with holes in the knees. She looks 48. She’s 76. She colors her hair, she tells me, uses moisturizer, and wears lipstick and mascara. “I’m the girl who wrote the letter to the newspaper because I didn’t like the word ‘senior’ printed on my parking sticker,” she says.

She’s Armenian but was born in Watertown — “the Armenian city of Watertown,” she says. Her family was tradition-bound. “I was taught to put everyone else’s needs before my own. Provincetown was all about me, and that made it very special,” she says. She first came to town in 1977.

A Piggy’s poster hangs in her bathroom. “You know where it was,” she says, as if the place where, until 1982, what David Dunlap called “an exuberant — often bacchanalian — cross-section of town” danced until the wee hours, had closed just yesterday. “We danced there all the time,” says Markarian. “Joe Cocker came and sang there unexpectedly one night.”

In 1980, Markarian married Victor Powell, the sandal maker and proprietor of the leather workshop above the Old Colony Tap on Commercial Street. Powell died in 2022.

She and Powell bought their house on Howland Street in 1987, complete with three rental units. David Schoolman, who had taken over the Land’s End Inn in 1972 and set out to enlarge and embellish it, turning it into a favorite place for parties, sent her all his leftover beadboard, which Markarian and Powell used to renovate the 1940 ranch house. The beadboard runs along the walls of her living room, painted white. “I’m really lucky,” she says of having her own place.

A painting of the Sun by Brian Bomeisler hangs on the beadboard in her living room. Below the painting is one of Powell’s sculptures. “I don’t know if Victor had a name for it — it’s a leather clam sculpture,” she says. Chris Stapleton’s “Cold” plays from a speaker, and Dolce, her goldendoodle, roams the room.

Markarian worked in Cambridge at the Harvard Coop in 1972. “Harvard Square was a gas” then, she says, though it’s “not so hip now.” She lived in Cambridge until 1975, when she moved to Wellfleet to work at Captain Higgins, which was down on the pier back then, for the summer.

Two years later, she landed in Provincetown. “I didn’t know anybody,” she says. Dancing with a guy at Piggy’s, she asked, “You know anyplace where I can live?” He helped her land a spare room at Will and Rhoda Rossmore’s house at 43 Commercial St., on the beach. “Everybody lived on the beach in the ’70s, even if you were a waitress or a cook,” she says.

Markarian took a job as a cook at Napi’s. “We had an all-girl staff at that time,” she says. That first summer in Provincetown, Napi and Helen came to the West End every day on their sailboat to pick her up right off the beach.

She met Powell one night at Back Street at the Gifford House. A friend from Napi’s set them up. “She said, ‘I got the guy for you.’ She just made a guess. We were together 44 years. Great guy, and handsome, too.”

She and Powell opened a leather shop called Skin in Lopes Square in 1982. After 17 years they moved to the space above the Old Colony and gave it the name Victor Powell’s Workshop. Markarian managed the shop and assisted Powell in making belts, sandal straps, and repairs. But when money was short in the first couple of years, she’d take other jobs, too.

She still works in the shop, one day a week, with Flo Mauclère, who apprenticed with Powell for five years before taking over the place in 2020. “I still got my hand in there so I could be near to Victor,” she says.

Markarian gets up and walks to the back of her house past a Philip Roeber painting of what looks like a bag of buttered popcorn. She opens her charcoal-painted “memory cupboard,” full of old photographs of friends, performers, and people from town. A photo of the actor and drag queen Divine is pinned to the left door of the cabinet.

“I just happened to be walking by,” Markarian says about the day Divine drove her Volkswagen Beetle the wrong way down Commercial Street and rammed into the hardware store. “She stepped out of her car wearing little ballet slippers,” Markarian says.

Markarian was on the board of the Provincetown Theater Company for a decade. “We didn’t have a space; we had to move around place to place,” she says about the theater in the 1980s and ’90s. They kept their props and other items for the theater in a trailer, and she ran the box office out of the leather store.

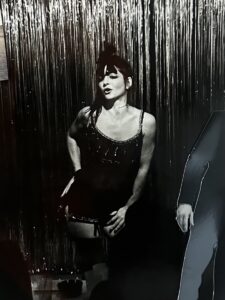

She also acted. Markarian’s first role with the company was in Cabaret. The theater put it on in the back room at the Crown & Anchor. When she got in line for the audition it snaked through the parking lot. Still, “a friend and I got really great parts,” she says. “It was the first time I’d done anything like that — we were the two ladies in the play — she was tall and blond and I was dark. That’s me in Cabaret in 1978,” she says, pointing to a photo on the wall.

Markarian usually wakes up at 9 a.m. but lingers in bed reading until about noon. She keeps a small pile of collected obituaries from the newspaper in a box next to her bedside. The obits keep her feeling close to town. She’s also currently reading America’s First Daughter, a novel by Stephanie Dray and Laura Kamoie based on letters written to and by Thomas Jefferson. She might smoke a joint while she reads.

Her house backs up to the woods, which has turned her into an adept birdwatcher. But she’s been having trouble identifying the Carolina wren. “I’m still trying to learn it — red stripe above the eye and a white stripe under the tail.”

As she speaks, the sunlight reflects off her bracelet, which is full of charms she’s collected from around town. “I feel like Provincetown has embraced me in every way,” Markarian says. “Everybody’s free to be true to themselves here, and I really like that. It doesn’t matter who you are — you can make it work.”