As you learn the night sky, you tend to associate the seasons with the stars or constellations they reveal. Winter is Orion, the season for observing both the striking constellation and the several bright, colorful stars that reside within its bounds and nearby. In spring, the constellations Leo and Ursa Major (of which the Big Dipper is a part) are at their best. Summer is for the Summer Triangle and the Milky Way. Fall, for me, is the time of Andromeda.

Andromeda is a character in Greek mythology, a constellation, and a galaxy. According to myth, Andromeda’s mother, Cassiopeia, queen of Ethiopia, unwisely boasted that her daughter was more beautiful than the Nereids (sea nymphs). The Nereids heard this and complained to their father, Poseidon, god of the sea. Infuriated by an insult from a mortal, Poseidon sent a terrible sea monster called Cetus to terrorize the coast of Ethiopia.

Andromeda’s father, King Cepheus, decided that the only way to save his kingdom was to chain his daughter to a rock and leave her for Cetus to devour. Things did not look good for Andromeda until the hero Perseus, on his way home from slaying Medusa, heard her cries. But before doing anything to help Andromeda, he first visited her father to strike a deal: “If I kill the monster, I get to marry your daughter.” Cepheus agreed, Perseus killed the monster, freed Andromeda, and they married.

Perhaps in compensation for such shabby treatment, there’s a constellation named for Andromeda. You might think that she’d be given something spectacular for her troubles; sadly, her constellation is unremarkable, lacking a clear form or bright stars. Even worse, she is surrounded by the constellations Cepheus and Cassiopeia. (Yes, despite such terrible parenting, these two have constellations named after them.) Even Cetus lurks nearby.

But then there’s Andromeda the galaxy, where she finally gets her due.

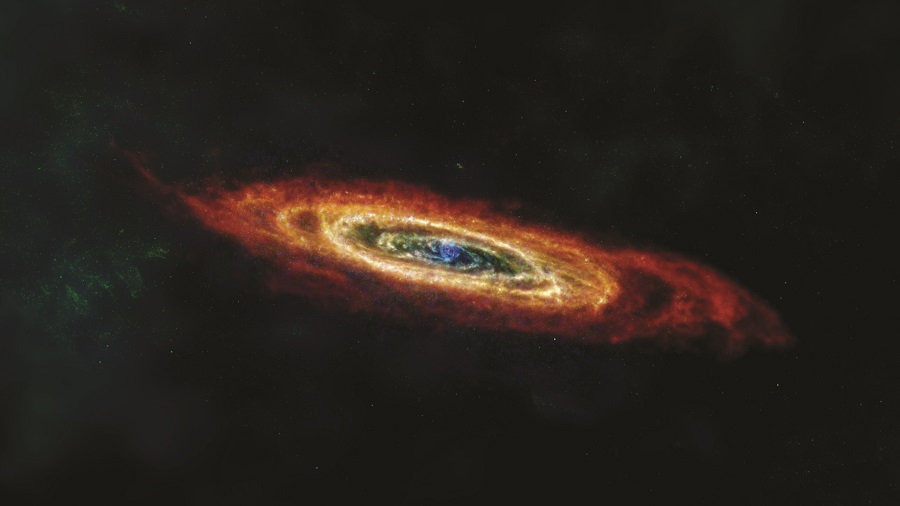

Galaxies are systems of billions or even trillions of stars bound together by gravity. They can take the form of amorphous clouds, vast ellipses, or grand spirals. Our home galaxy, the Milky Way, is one such spiral. Andromeda, our nearest galactic neighbor, is a near-twin.

Both galaxies have super-massive black holes at their cores, around which their stars orbit. The Milky Way is about 100,000 light-years in diameter; Andromeda is about 150,000. New stars are constantly forming in both galaxies’ spiral arms, while older stars crowd the cores.

Photographs of Andromeda taken by amateur astronomers and orbiting observatories show a beautiful spiral, glowing with billions of stars. It is a reflection of our own home. But you do not need the James Webb Space Telescope, or any telescope at all, to see Andromeda. In autumn, Andromeda is well positioned in the night sky.

Head outside after dark and find the darkest location you can, far away from lights. Andromeda is faint, so give your eyes at least 10 minutes to adapt. No smartphones allowed! One glance at a text will ruin your night vision.

Look up to the northeast, about halfway up the sky. You’ll see a slanted W shape (if you’re out late, a sideways W; if you’re out very late it will be an M). That is Cassiopeia, the constellation we need to point the way to Andromeda. (One of the star guides I mentioned in the Aug. 17, 2023 issue of the Independent would also be very helpful.)

Look for the brightest star of Cassiopeia, on the bottom right of the W (or top left of the M). The two adjacent stars form an arrow shape with it, pointing away from the constellation.

Follow an imaginary line extending from the arrow until you reach a star of about equal brightness. That’s Mirach, part of the constellation Andromeda. Very close to Mirach back in the direction of Cassiopeia is a faint star. Follow the line formed by Mirach and this faint star a short distance toward Cassiopeia — about the same distance as the two stars are from each other. Here you’ll find Andromeda, not a star, but a faint fuzzy.

If you have a very dark sky and you’re on the young side, you may be able to see Andromeda directly: a gray, fuzzy-edged, oblong ghost, about as large as your thumb held out at arm’s length. Most of us will see something flickering at the edge of our vision, but when we look straight at it, it will vanish.

This is because our eyes are more sensitive to dim light when it is off-axis — at an oblique angle to our vision. Experienced observers learn to use averted vision: looking just to one side of the object you’re trying to see while redirecting your mind’s attention to that object. It’s a strange mental exercise, which you’ll get better at with practice.

The reward is seeing Andromeda. At first you may wonder what’s so great about seeing a faint smudge in the sky. But then you’ll remember that what you’re seeing is about 2.5 million light-years away. The light from Andromeda reaching your eyes right now started on its way 2.5 million years ago, when saber-toothed cats roamed North America, lush grasslands covered the Sahara, and Homo habilis, one of our now-extinct ancestors, was learning to control fire.

That smudge is billions of stars and trillions of planets, 150,000 light-years across. Someone over there may be looking up, just as you are, and marveling at the ghostly shape of our Milky Way galaxy. Or maybe not. But it does no harm to wave and smile. Clear skies!