Escapism is a form of self-care, and self-care is a high priority right now for Provincetown residents facing months of winter. Good reads — like batteries, chocolate, moisturizer, and canned beans — are the foundation of a winter survival kit, and a stack of books can be a soothing way of marking off the days. But an escapist novel shouldn’t be too taxing. So it’s the perfect time to greet everyone’s favorite 50-something, anxiety-riddled, minor American author Arthur Less in Less Is Lost, Andrew Sean Greer’s sequel to his 2018 Pulitzer Prize winner Less. Proust can wait.

The engine driving the plot is economic necessity. Arthur, our protagonist, has lost a former lover and benefactor who allowed him to live in an apartment in San Francisco for a decade without paying rent. At the deceased lover’s memorial, the apartment is revealed to have been rent-deferred rather than rent-free — and now payment to the estate is due. The only immediate money-earning opportunity is to accompany a cantankerous science fiction writer on a book tour and write a magazine profile that Arthur believes will generate at least a third of the sum needed to save his home. Does this math add up? One third of ten years’ deferred rent in San Francisco would be in the vicinity of — well, numbers are hard, but it would have to be a lot more than any magazine on Earth could afford for a profile.

Later, another source of desperately needed income emerges from a stage production of one of his stories by a theater troupe in Louisiana, which sends Arthur racing off toward it. I don’t know what a theater troupe in Louisiana might charge for tickets, but it’s probably not going to cover the gas to get there. Still, the idea that a middle-aged gay man from San Francisco would go to extreme lengths to protect his real estate investment is completely believable. Satan himself couldn’t get between a San Francisco queen and his condo.

Arthur’s most notable personality traits are consistent bafflement and low-grade anxiety. He sits at his desk and sees his reflection as “a demon staring back at me with red-rimmed eyes and growling.” Greer, a writer who writes about writers struggling to write, manages to neatly sidestep a potential quagmire. Writing is a torturous profession made of equal parts misery and more misery. But to nonwriters, what is so vexing about writing rarely translates in a comprehensible way. Compared to more easily understood high-stress jobs like defusing bombs or being a mall Santa, it’s hard to imagine what all those griping writers are going on about.

Yet Greer manages to keep his character’s problems broad enough to be relatable, even if some of Arthur’s potential faults seem like virtue signaling. Arthur is labeled a “bad gay” by other gays because he’s uptight about having lots of sex with many different partners. “Am I the only frigid homosexual in New York?” he wonders. (Maybe, but is that really a negative?) Later, it’s revealed that his sexual kink is long underwear, which even for a basic gay is pretty bland. When pressed to share his philosophies, he responds in platitudes: don’t buy tomatoes in winter, men over 40 shouldn’t dye their hair, expensive underwear is worth it. Surely, even Grandma would approve of Arthur Less.

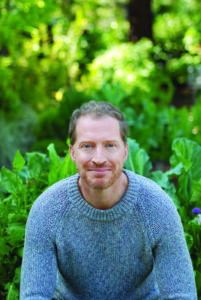

Physically, the character comes into view slowly. We know he’s tall, blond, 50-ish, and considered handsome, if very pink and balding. Arthur is repeatedly described as “a minor American writer” and winner of a notable prize — which sounds a lot like Greer, whose Pulitzer set off some serious side-eye by the snootier literati who deemed a comic novel insufficiently lofty. Arthur is befuddled by his success and acutely aware that it hasn’t elevated him in literary circles as much as the prize implies; Greer, like his protagonist, is still relatively obscure.

The humor in Less Is Lost is gentle and heavily foreshadowed. By the third time Arthur has been warned not to tamper with a particular hose, you can be sure he will. Later, he is discombobulated when the grumpy sci-fi writer refers to him as reckless. The narrator of the book (who is not Less, but I shall say no more) asks us, “Who has ever spoken of Arthur Less this way? Who has ever so misunderstood him? Or is it the rest of us who have been wrong, who have ignored all the signs and portent that this slapstick, ridiculous, zigzagging queer is in fact a reckless man? Capable of anything?” None of those adjectives had entered my mind. Nearly halfway through the book, I was still waiting for him to do something surprising.

But the net effect of all this mild chaos is a novel that provides an easy escape from the winds outside. Though Greer has said that this is the end of Less and his wild road trips, I would guess that popular demand, a rare thing in today’s publishing world, will inspire more tales. Let’s hope so. The summer months are short.