One of the pleasures of reading a memoir is witnessing a character make the same mistakes over and over again. Novels rarely leave room for this. By the last page, the protagonist has been magnificently transformed, while you, sunk into the couch and on your third glass of wine, remain the same old person. Memoirs, on the other hand, mimic the motions of actual life.

In The Secret to Superhuman Strength, Alison Bechdel writes, “Over the course of my life, as I have made my Houdini-like escapes from one self-imposed constraint after another, a question haunts me with increasing insistence: How many levels does this game have?”

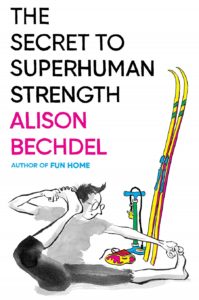

Bechdel’s memoir is a comic book. That doesn’t mean it’s an easy read. A MacArthur fellow and the eponym of the “Bechdel test,” she once described her 2006 graphic memoir Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic as being about “how my closeted gay dad killed himself a few months after I came out to my parents as a lesbian.”

Superhuman Strength takes on Bechdel’s lifelong relationship with exercise. “My bookish exterior perhaps belies it,” reads one speech bubble, “but I’m a bit of an exercise freak.” In the panel, avatar Alison is adjusting her wire-frame glasses with one hand while lifting a dumbbell with the other.

On a page illustrating what Bechdel calls the current “exercise epoch,” women are decked head to toe in Lululemon, action lines are shooting like sunbeams from participants in a spin class, people have contorted their bodies into the shape of a “Y” inside a yoga studio, men with tree-trunk thighs are hurling weights over their shoulders, and a row of women lying in missionary position are being chastised by a Pilates instructor for not engaging their core.

Unlike Fun Home, which is illustrated in a sullen shade of grayish blue, Superhuman Strength is rendered in screaming colors — green mountains with white snow caps, tie-dye leggings and firetruck-red bicycles, yellow and red beach towels dotting what appears to be a Provincetown beach. Bechdel’s wife, the artist Holly Rae Taylor, helped with the coloring.

“What gnawing void propels this cardio-pulmonary frenzy?” Bechdel asks. “The spiritual and moral bankruptcy of late capitalism? The disembodiment of our increasingly virtual existence? A bottomless credulity that ‘6 weeks to a 6-pack’ is humanly possible?”

Bechdel doesn’t spend much time on this question. She describes her relationship to exercise as rooted in a desire for transcendence: experiencing the self not as a separate entity but as inseparable from the universe.

She found this transcendence for the first time while playing catch with a tennis ball by herself as a kid. “In time, I learned that the secret to mastering the wooly orb was not to try, not to think about it, not to think at all,” she writes. At that moment, she became “one” with the tennis ball. She transcends herself again during her first jogging-induced endorphin high when “the boundary of my very self seemed to dissolve as I merged with the humid evening air.” The graphic is a map of Bechdel’s hometown and of Alison running further and further beyond the town line.

Eventually, this desire becomes a problem. In adulthood, Alison pursues karate, cycling, yoga, spin, weightlifting, high-intensity interval training, and hiking along risky trails in pursuit of this feeling. Rarely does she achieve it. And yet, each time, she’s convinced that she’s finally gotten it right: “Had I found it? The secret to superhuman strength?!” serves as the book’s central refrain.

This takes a toll. As cartoon Alison grows older, the curved smile is replaced by a straight-lined frown. The wonderful thing about a graphic memoir is that you can easily track change and continuity over time by comparing the illustrated panels: 60-year-old Alison doing the exact same yoga pose as 20-year-old Alison, just with a more expensive yoga mat; or Alison blocking out her wife by staring obsessively at her laptop, much as she blocked out her first girlfriend by gluing herself to her typewriter.

Near the end of the book, Bechdel writes about her realization that “we are not the center of everything” and that better than transcending the world is transforming it, here and now, with one another. The accompanying illustration is brilliant: Alison and Holly, cloistered by the pandemic, are in their living room as Trump is on the television declaring, “Fraud! I won!” But Alison and Holly are not paying attention, not even looking at the TV. Instead, Holly’s speech bubble reads “Walk?” and Alison’s reads “Yes!”