Alexis Trice lives in New York City, where she was born and raised, but it’s the natural world that has captured her imagination. Her jewel-like, unsettling paintings of dogs (often swimming, drowning, or crying), glistening bivalves, and suspended still lifes are informed by experiences both typical and eccentric: childhood trips to the beach, a former job in the invertebrates and zoology department at the American Museum of Natural History, a past career as a pet portrait painter, and a fascination with fastidious painters from art history.

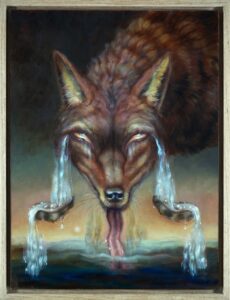

In Trice’s current exhibition at Gary Marotta Fine Art, her second with the Provincetown gallery, one painting memorializes a coyote she encountered here last summer. “It was the first coyote I had seen in a very long time,” Trice says. “She was so stunning. I was elated.” The next night, Trice saw the coyote again, but this time it was dead, lying on the side of the road. And in the morning, it was gone.

Wild Eyed is a portrait of the animal. The coyote looks at the viewer through squinting eyes, from which rivers of tears fall, cascading off pearl-filled oysters before flowing into the ocean. It’s twilight, and the sun hovers just above the horizon.

The painting, and Trice’s story about the coyote, reflect themes that reverberate in the exhibition. It makes sense that a coyote would stop her in her tracks — she’s fascinated by the rich, strange beauty of nature, like the iridescent scales of a fish or the soft, wavy hair of canines. In The Warmth of the Hour, a whale rises from an emerald sea like a revelation. Her paintings of clams and oysters, gleaming in their juices, feel decidedly fetishistic.

Along with beauty, danger lurks in Trice’s paintings. Most of her dogs are slim, elegant creatures with shiny coats, but they aren’t coddled pets. They seem both threatening and threatened. They have sharp teeth and lots of saliva, and they could be wolves or coyotes. “They’re a hybrid of them all,” says Trice. “I try to make them ambiguous.”

In one painting, a salivating dog is about to bite the leg of a posing, golden-haired dog. In Salt of the Earth, II, Trice pushes the dog’s head against the confines of the painting’s square surface. The dog has hardly any space to breathe in the composition, and the sea, filled with monstrous seaweed, rises.

A few of her paintings include candles. In High Spirits, one burns in a shell above a fish that seems to have jumped out of the water. Trice nods to Dutch still-life paintings in this work. Here, as in those paintings, there’s a concern with mortality that’s mediated through objects like a burning candle but also in gleaming surfaces, like Trice’s gorgeously painted fish. She accesses the metaphysical through attention to materiality.

Trice received a degree in illustration from New York’s School of Visual Arts in 2004 but came away more devoted to oil painting than illustration. Animals have long been a preferred subject. She began painting pet portraits shortly after finishing art school. Eventually, she felt those commissions were holding her back from a commitment to creating her own art. “You really can’t do both with the same amount of energy,” says Trice.

Since making that commitment, her work has dramatically shifted. “I started spending more time outdoors,” she says. She’s also spent more time in her head. “I really immerse myself in my thoughts and inner dialogue.” As a result, her paintings have one foot in a world of imagination and one in the natural world.

This duality guides Trice’s use of animals and objects in her paintings. In Self Portrait at the Sea, she depicts a halved clam with an attention to detail reminiscent of Victorian-era illustrations of the natural world. Her paintings are a way to gain a deep connection and understanding of animals, she says. But there’s also a symbolic and narrative component to these paintings that belongs to the human world.

“Dogs have always been a huge fixture in my life,” says Trice, and in her work, they become “conduits for expression.” Pearls become symbols of the transference of emotion and energy. In a statement accompanying the exhibition, Trice writes about water “as a source of our own universal emotions and traumas: joy, fear, ecstasy, anguish, and all the tears we at times try to keep hidden away.”

Trice’s use of twilight colors echoes the symbolic logic of her paintings. The world she creates is one of transition. It’s decadent and beautiful but not safe. The day is over, yet night has not yet come. There’s pleasure in this world, suggested by her erogenous mollusks, but also rivers of tears. And there’s luxury, but it’s no stable destination. In Two Sides of Myself, a pair of ravenous canines hold a string of pearls between their teeth.

Contradictions run rampant in Trice’s world, and the ocean, perhaps more than any other symbol in her work, has complex associations. Its surfaces reflect the light at dusk in rich, romantic colors, but Trice uses transparent washes of paint to show us what’s underneath the water, like chaotic, swirling seaweed.

For Trice, the ocean is a place of peace, intrigue, and fear. It’s the ideal setting for the intricate world she articulates in her painting practice. “It’s a place to experience fear, risk, and reward all in one,” she says.

Stopped in Her Tracks

The event: An exhibition of paintings by Alexis Trice

The time: Through July 17

The place: Gary Marotta Fine Art, 162 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free