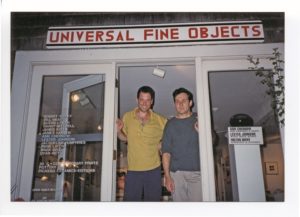

After 35 years in business, Albert Merola and Jim Balla announced last month that their gallery at 424 Commercial St. in Provincetown’s East End will not reopen for the 2023 season.

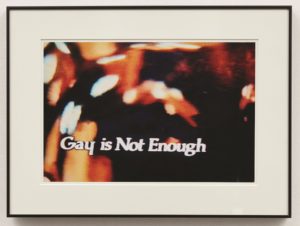

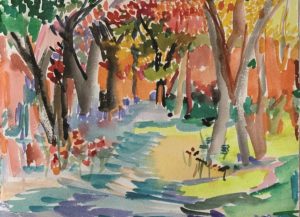

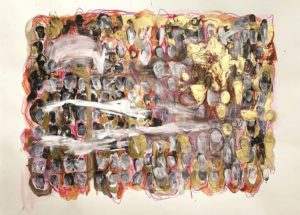

The first reaction of this longtime observer of the local art scene was dread. Then curiosity: what happens when a gallery like Merola’s closes its doors? Where will its displaced artists — a roster that includes celebrated figures like Lyle Ashton Harris, Jack Pierson, and John Waters, established mid-career painters like Tabitha Vevers and Irene Lipton, and the estates of legends like Fritz Bultman and Michael Mazur — show their work in Provincetown?

What will become of our status as a center of art viewing and making if these and other artists don’t return for shows every year? Not to mention what will happen to artists who live full-time on the Outer Cape and are steadily losing places to show locally. As Provincetown’s real estate market thrives, its galleries continue to shut down.

Photographer Curtis Speer’s Cusp Gallery announced it will be moving to Newport, R.I. this spring. Kmoe Gallery announced its closing last October. Around the same time, AMP (Art Market Provincetown) closed its doors for good. And while AMP’s Debbie Nadolney remains positive about the future of the local art scene, she acknowledges concerns about the long-term fate of brick-and-mortar galleries.

“I worry about how expensive running a gallery has become,” she says. “It’s hard to get around that.”

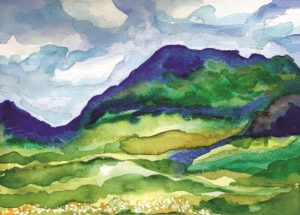

Despite these and other closings, we continue to think of Provincetown as an artist colony with a long and illustrious tradition. In 1898, Charles Hawthorne founded the Cape Cod School of Art and revealed the secrets of shadow and light to acolytes, mostly women, who set up easels along the bay. Forty years later, Hans Hofmann drew excited crowds to his studio demonstrations. Artists who answered Hofmann’s call, like Robert Henry and Selina Trieff, returned to live on the Outer Cape and serve as teachers and mentors to new generations of artists.

My own parents — who bought their home in the East End gallery district, sanctified in the 1950s by painter Jim Forsberg’s art supply shop, a gathering place across from Kiley Court — studied with artists Seong Moy and Irving Marantz. It’s this generational flow that sustains our sense of Provincetown as an arts community.

A mission of the Fine Arts Work Center, founded in 1968 by artists and writers, was to “seed” that community with emerging artists by awarding short-term and potentially renewable fellowships. But while FAWC continues its robust fellowship program and has been able to successfully pivot to other worthy projects, that initial goal — attracting younger artists who would remain in town — is no longer sustainable.

We’ve seen cycles like this before. The town’s art scene was swinging in the 1960s, when Robert Motherwell and Helen Frankenthaler held court in the East End, drawing the likes of poet Frank O’Hara and painter Grace Hartigan to their parties. A decade later, Long Point Gallery was founded with the idea that the presence of a collective of “blue chip” artists, inspiring each other and hosting public exhibits, would help keep Provincetown on the art map. The galleries of those years are gone now, and new ones have taken their place. Change is constant.

And even if some fear that a world gone virtual is a world gone wrong, the optimists — makers and doers all — say otherwise. Under the leadership of Cherie Mittenthal and her board, Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill passed its half-century mark last year and continues to build infrastructure, faculty, programming, and residencies. FAWC and the Provincetown Art Association and Museum are year-round magnets, offering in-person shows, workshops, and performances as well as online programs for writers, artists, and audiences gathered across space and time. And stalwarts like Marla Rice and Berta Walker continue to plan real-world exhibits featuring artists who span creative generations.

Still, Nadolney sees the town’s creative scene evolving toward a looser structure, one that is untethered from traditional spaces. Artists, including ones associated with AMP, have been showing at innovative, multi-purpose venues around town like the Provincetown Commons. “The gallery structure is being challenged,” says Nadolney. “Artists are feeling that they want more freedom, and people are hungry for things that are easy and accessible. It’s a brave new world out there.”

Balla and Merola share Nadolney’s tempered “glass half full” optimism.

“Artists need to be resilient,” says Balla. “Self-employed gallery owners do as well. It is certainly in the spirit of Provincetown. But will that resilience be enough for the next group of decades-long galleries to flourish?”

Whatever else they do, Balla and Merola say that they plan to continue working with artists to explore different avenues of creativity and expression. For every venture, there is a season.

“We are not leaving Provincetown,” says Balla. “You will be seeing more of us.”