As more and more music making goes online — with YouTube videos, pre-recorded concerts, and live-streams — music critics are having to become more like film critics. They are having to analyze things like lighting, camera movement, and editing in relation to the listening experience.

For example, Les Arts Florissants, a Baroque ensemble, recently gave a virtual winter concert, playing pieces by Henry Purcell, Henry Eccles, and Nicolas Matteis. The beautifully produced video makes the cavernous French church in which they perform an integral part of the event. Light streams through the stained-glass windows. It’s so cold that you can see the mezzo-soprano’s breath — which is especially poignant when she sings “When I am laid in earth.” It’s hard not to shiver.

Virtual concerts are different from other types of films in that their main function is to faithfully reproduce a musical performance — something especially important in classical music. A film theorist might simply call it realism. Set up a solitary tripod in front of an ensemble and press record — you have a virtual concert. It might not be very interesting, but it does the job.

The visual component in a virtual concert also lends an authenticity to the audio, which can be more easily (or invisibly) altered — it somehow “proves” the performance actually happened as you hear it.

Indeed, excessive camera cuts can be a drawback. People in the audience at a live performance get to choose where to look — perhaps at the grooving bassist, or the piano soloist, or at the charismatic conductor. But in a virtual performance those views are predetermined. If the cuts don’t correspond with what viewers want to see, they can feel manipulated.

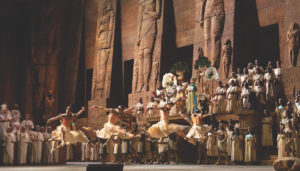

For instance, the Metropolitan Opera started doing simulcasts long before the pandemic. Opera, being halfway between music and theater, ought to lend itself well to film.

But in the Met’s 2012 production of Aïda, which is available on the app Met on Demand, the “triumphal march” crowd scene in the second act presents a challenge. The cast is so enormous, it’s impossible to see everything at once. The camera takes the place of opera glasses, cutting to close-ups of the singers and dancers. Sometimes, they are even shown from above.

But some of the majesty is lost in the process. Seeing a stage full of people in person is impressive — seeing it on a small screen is underwhelming.

Some virtual performances, however, are pieces of art in themselves. One example is a video of the Vivid Consort, a Vienna-based group, performing John Dowland’s “Can She Excuse My Wrongs.” It is full of symbolic and carefully planned details.

The room they play in is a modern re-imagining of a Netherlandish vanitas painting. It’s IKEA meets Van Eyck. The camera pauses over a skull, a butterfly pinned to a board, dead flowers. All of this creates a powerful mise-en-scène — a visual sense of the three-dimensional space.

The sheet music seen on the coffee table is an allusion to Renaissance table books. These were musical parts printed in different directions on a single piece of paper so they could be played around a table.

The close-ups, coming softly into focus, highlight the performers’ fingers and instruments. They make viewers feel as if they are sitting on the couch beside them. They have a slightly random feeling to them, suggesting they were decided in real time. The florid recorder interludes, full of rapid diminutions, sound almost improvised.

In one shot, the reflection of the cameraman is shown in a lampshade. It’s an allusion to Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait, with its convex mirror in the background. At the same time, it creates a transparency about how the video was made. At the end, the camera pans out to reveal the sound engineer and recording equipment. The musicians breathe a sigh of relief after recording the winning take.