PROVINCETOWN — On an unseasonably hot Friday in May, local leaders from Cape Cod, the Islands, and the Berkshires gathered at town hall to discuss the state’s newest response to the worsening housing crisis: the “seasonal communities designation” created by last year’s Affordable Homes Act.

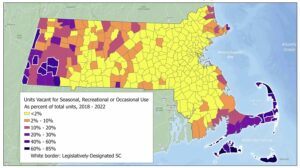

The designation provides policy tools to towns that face a burgeoning market for vacation homes that has made it difficult for many year-round residents to secure housing. Previously, towns had to come up with their own policies, pass them at town meeting, and then get the legislature to approve them as home-rule petitions, but the new law created a Seasonal Communities Advisory Council for discussing ideas for solutions and asking the state to turn them into new legal tools.

A large group assembled for the May 16 council meeting in Provincetown, including Lt. Gov. Kim Driscoll, Secretary of Housing and Livable Communities Ed Augustus, state Sen. Julian Cyr, state Rep. Hadley Luddy, and select board members and town staff from Provincetown, Truro, Wellfleet, Eastham, Orleans, and Brewster.

Driscoll said the state’s aim is to build more housing “for the individuals who live here now — families, young adults, folks who want to age in place with dignity and respect — but also for the next generation.

“A lot of 26-to-35-year-olds are leaving the state because they can’t do the thing that many of us had the chance to do when we were 26 to 35, which is buy a house, put down roots, and contribute to your community,” said Driscoll, who described settling in Salem as a young adult after growing up on naval bases around the country.

There are “lots of intractable problems in government, but this isn’t one of them,” Driscoll added. “We just need to figure out how to build more housing.”

The designation — which has already been accepted by voters in Provincetown, Truro, Wellfleet, and Eastham — requires towns to adopt bylaws permitting deed-restricted year-round homes on undersized lots and to incorporate tiny homes into their bylaws. Council members discussed the details of those provisions.

There’s “a real distinction” between tiny homes “that aren’t movable, that are true investments, versus homes on wheels,” said council member Kevin Galligan, a select board member in Orleans, “so let’s make sure we define that.”

Council members also discussed a provision allowing towns to build housing specifically for public employees such as teachers, police officers, and firefighters, who often earn too much to qualify for affordable housing but not enough to buy homes at market prices.

Laura Silber, a council member from Martha’s Vineyard, said that “the fire departments on Martha’s Vineyard are almost entirely volunteer,” and towns there would like “trained volunteer personnel” to be eligible for town-built housing.

“In the coming decades, we’re going to have to figure out how to provide housing for almost all public employees” in many seasonal towns, said Cyr. Home prices on Nantucket have already surpassed what even department heads can afford, and other towns will soon find that their entire public workforce will need some kind of housing support, he said.

Luddy asked whether health-care workers and commercial fishermen could be added to the list of occupations for which towns could build dedicated housing, while council member Alisa Magnotta, executive director of Housing Assistance, asked if child-care workers could be included.

“The other crisis that’s happening in the region is we don’t have enough child-care workers,” said Magnotta. They are paid even less than home health aides and certified nurses’ assistants, yet they are “essential to the economy” and especially to women’s ability to rejoin the workforce, she said.

Allowing towns to build housing for more categories of employees would require an update to the legislation, Cyr said, because fair housing laws require publicly funded units be available to everyone, and new laws are needed to carve out exceptions.

Such legislation was not out of the question, Cyr said, adding that “I think you could make a really good case for health-care workers.”

Driscoll raised another issue she hoped the council would consider: a growing need for supportive housing for elders on Cape Cod, as well as for young adults with autism.

“Is there a way to put that on speed dial or offer some special consideration in permitting?” Driscoll asked. “Congregate housing can be hard to zone for. How do we figure out a way to offer the support that’s necessary?”

Silber said that the legal tools in the current designation need to be supplemented with a revenue stream such as a local-option real estate transfer fee, which failed in last year’s legislative session.

“We’re going to need funding to fully implement these tools. This is a shout out to your administration for your support of the transfer fee,” Silber said to Driscoll, “and we certainly hope you can get it across the finish line this session.”

About two dozen people turned their gaze to Driscoll, and after a brief pause, she decided to aim for levity: “I blame Julian!” she said, to laughter.

Council members agreed on the importance of the transfer fee and moved to discussing next steps for the council. There will be three “public listening sessions” over the course of the summer organized by the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities that will allow the public to comment on rules that are being developed and future policy ideas that the council could take up, followed by draft regulations and a formal public comment period.

The next full meeting of the 24-member council will be on Nantucket in September, although various subcommittees will continue to meet between now and then.