Evening’s colors and rain figure in many of Adam Matthew Graham’s paintings, especially in his streetscapes, where the glow of lamplight or the shimmer of a puddle suggests that the storm is over. Lately, though, he’s been sketching historical scenes in tones of black and gray. He’s absorbed in a new project, which is still at the idea stage, he says. And that, for him, is a big part of the process.

Using his iPad, Graham scrolls through online images from the Library of Congress in his Provincetown studio. He’s focused on the early 20th-century photographers who paved the way for American photojournalism. He selects images for their formal appeal and the values they capture. By “values,” he says he means both the relative degree of light and dark and the moral values they reveal.

He stops at a photograph by Lewis Wickes Hine, whose early 1900s documentation of children in harsh working conditions helped achieve passage of child labor laws. The information accompanying the photo identifies the child in it as “Rosie,” who is “illiterate” and “a regular oyster shucker.”

“Have you ever shucked an oyster?” Graham asks — his point being that you can easily get hurt doing it. Another of Hine’s photos is dated 1910 and depicts two boys identified as “newsies.” They’re not just selling newspapers, they’re smoking, too.

Graham is making mixed-media drawings of these photos, inspired by the Ashcan School. The Ashcan artists, known for their gritty paintings of urban life, worked mainly in New York in the early 1900s and did sketches for newspapers before photography was widely used. Graham’s drawings are a personal response not only to the subjects of the photos but to the formal beauty and distortions — inconsistencies in focus and imperfections from developing — of the originals.

In his version of Rosie, he closely delineates her features while transforming the blurry background into a field of abstract-expressionist-like brushwork. In contrast, his “newsies” strips away some of the boys’ youth through a lack of detail but remains true to the original photo’s stark contrasts of light and dark. The smoke from one boy’s pipe is a masterfully controlled daub of paint. Its effect, like Rosie’s background, points up the loss of an authentic childhood.

Graham calls his new direction “the American Values Project,” and the impetus behind it is the current emergence of oligarchy and assault on the pursuit of truth. He’s been thinking, he says, that “the most important, relevant thing I could be doing right now is defining what it means to be American, because that is not something there is any consensus on. And that lack of consensus has gotten us into a terrible situation.”

The Ashcan artists aren’t his only influence. Graham is inquisitive, a reader, and ventures into philosophy. A conversation with him can run the gamut: Edmund Husserl, Caravaggio, Banksy, Jimi Hendrix, neon lights, poker, and the immediacy and authenticity of art by children.

Graham first came to Provincetown as a child. His parents, who were artists in Atlanta, came here in the summer to draw portraits of tourists, working from the Starving Artists’ Studio on Lopes Square. His father also took classes at the Cape School of Art. “He did block studies and still life during the day over on Pearl Street with Henry Hensche,” he says, “and then at night he’d go to the Starving Artists’ Studio and do portraits to make a living.”

In the late 1970s, after his parents divorced, Graham’s father moved with him and his brother to New Orleans for its vibrant arts scene and numerous passersby to sketch. Graham has a trace of an accent from the city where he took up the same work as his father.

When his son decided against applying to the University of New Orleans, Graham’s father told him, “Well then, you got to go to work.” And so, he did. He was 17 when he got his license to sell art on Jackson Square and moved out to live on his own. His motivation to draw was primal: “I didn’t eat until I did my first cartoon,” he recalls. “Then I’d go to the patisserie and get my croissant and coffee for breakfast.”

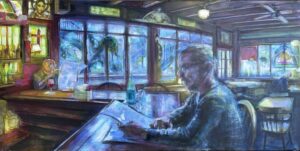

In 1999, when he was 24, he moved to Provincetown. After taking a few workshops, he settled into painting and a job washing dishes at Napi’s. He became known here for his paintings, mostly oils, of street scenes and of the harbor that capture the evening stillness lit by headlights and neon signs in a manner that Graham describes as “what Hensche might do if he were alive today.” He was first represented at Sonny Bayer’s Impulse Gallery and later at Rice Polak Gallery; he now sells directly through his online Shank Painter Studio. He also works as a comic artist for the Provincetown Independent under the nom de plume A. Crock.

The apartment off Shank Painter Road that Graham shares with his girlfriend, Lessie Sargent, looks like an artist’s studio more than a dwelling. The living room is his studio; the only furniture a love seat and a dining table for two near the kitchen. A draughtsman’s table against the wall is his workspace. Lined up within easy reach are books that could have been lifted from the syllabus of a graduate course in art theory. Some of Graham’s finished works line a wall, and a still life by Hensche is hung high in a corner — a gift from his father that Graham says is a sort of “aesthetic North Star.”

Graham thinks a lot about the mythology of the artist’s life, the romance of existing outside the mainstream, of a kind of freedom. “You can’t really build anything with just freedom,” he says. “You need more than freedom.” He’s been reading on this. “I’m thinking of Kant’s responsibility in the existential sense.”

The question of how an artist enters into the social contract today is what has Graham looking back at Hine and the early photojournalists who were instrumental in the social welfare movement. It matters to Graham that “their photographs made the poverty that people were living in visible and real.” That kind of reality, he says, is “a story that has to get retold to survive.”

Equally interesting to Graham is the way the documentarians made their work. “These photos are important because they’re fixed — they’re analog.” Much of what we see today has been digitally manipulated, he says. “What we see as real or unreal is becoming slipperier,” he says, “and the distorted truths that result subject people to manipulation, which is responsible in part for people being unable to think for themselves.”

Graham has addressed this in his comics work: a man glued to TikTok is diagnosed with “brain rot.” In these drawings, working mostly in single frames not unlike the analog photos he has been studying, he captures local history, with caricature adding the distortion that invites a second look: darkness falls on Napi’s; Elon Musk appears at a town crier competition.

“My work has always been about reality — describing things as they actually are,” says Graham. “But the things I want to describe are phenomena, not things.”

In the same way that Monet and Hensche painted the light on the landscape, not the landscape itself, he says, he wants to paint morals, “our values and what they cost us.” The nihilism of this moment in American history absorbs him.

Graham is realistic about his current project, though; he envisions it as a graphic narrative-length work. “Check back with me in six months,” he says. No matter what it becomes, it is one artist’s reflection on what it means to be American.

Adam Matthew Graham will be teaching two mixed-media drawing workshops at the Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill this spring.